Sixty years on from Donald Horne’s instant classic, has The Lucky Country run out of luck?

Published in 1964 and serialised in The Australian, the impact of The Lucky Country was immediate and all-pervasive. Donald Horne declared that ordinary Australian people were not the problem: the elites were. Today that seems truer than ever before.

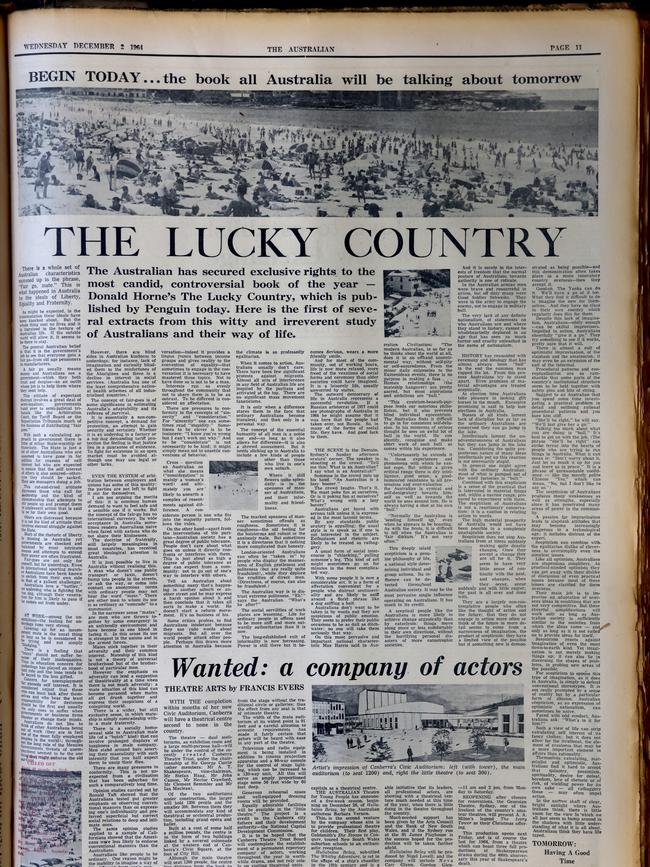

“Join the Lucky Ones” ran the front-page headline of The Australian on Tuesday, December 1, 1964. Starting the next day, readers could enjoy “the first big instalment of Donald Horne’s controversial new book The Lucky Country”, which was being published that week.

Horne had a long association with Frank Packer and Australian Consolidated Press, but in a publishing coup Rupert Murdoch’s new national newspaper had secured exclusive rights for “the most candid, controversial book of the year”.

The Australian had begun life less than six months previously as a daring experiment, the first nationally circulated newspaper in a country beginning to fizz with a sense of expanding possibilities yet faced with new, sometimes daunting prospects in a dramatically changing world.

Horne’s much-anticipated “witty and irreverent study of Australians and their way of life” couldn’t have found a stage better suited to its bold approach or for the questions it was firing, at point-blank range, into the national conversation.

Australians were reintroduced to themselves in the weeks that followed as a people who “hate discussion and ‘theory’ but can step quickly out of the way if events are about to smack them in the face”.

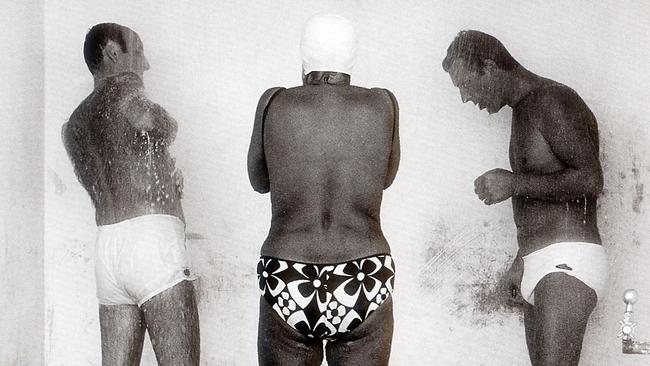

They found out that “to understand Australian concepts of enjoyment one must understand that in Australia there is a battle between puritanism and a kind of paganism and that the latter is beginning to win”. Competitive sport, they were now given to understand, had all the qualities of “a ruthless, quasi-military operation”, making it “one of the disciplinary sides of Australian life”.

As for mateship, it reflected “a socially homosexual side to Australian male life” that involved “prolonged displays of toughness” in pubs, where men “stand around bars asserting their masculinity with such intensity that you half expect them to unzip their flies”.

Perhaps most arresting was the argument that went with the title’s assertion. Australian life, combining scepticism and “delight in improvisation”, had resulted in dependence on a type of gambler’s luck.

As circumstances shifted, Australians’ “saving characteristic, ‘the gambler’s coolness’ ”, had helped them to “change course quickly, even at the last moment”.

But the aim of those swerves had always been to “seek a quick easy way out”. Now that strategy needed to be reconsidered.

Abrupt changes

The Lucky Country packed many punches – and they landed at the perfect moment.

The tremendous post-war growth of an educated and engaged public had been evident since the mid-1950s as new magazines proliferated and the market for Australian books expanded more prodigiously than at any other time in the century.

Coupled with that were global shifts even more dramatic and described in The Australian’s first editorial, which spelled out both the paper’s vision and the challenges the nation faced.

Since the end of World War II all the major European empires had ceded or lost control of the lands and people to Australia’s immediate north. As British, Dutch and French imperial power in Southeast Asia collapsed, new nations – including Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam – were born and ancient ones, such as Burma and Thailand, reshaped. Behind them lay “the brooding power and intelligence of the new China, a land with whose people’s desires and plans our own future is deeply entwined”.

These abrupt changes coincided with Britain trying to join the European Common Market, making it clear that wherever the United Kingdom saw its future, it was not primarily with the Commonwealth.

Losing the blanket of certainty that Australia’s close relationship with Britain had long provided was a blow. But, The Australian insisted, it could prove “a salutary shock”, as it helped us realise “that now, as never before in our history, we stand alone”.

Collection of snapshots

The Lucky Country’s impact was immediate and all-pervasive. Despite some scathing reviews (one confidently predicted the book would have been forgotten by the next football season), it flew off the shelves. Its initial print run of 18,000 sold out in nine days and the pace showed no sign of flagging.

In 1965 it sold another 40,000 copies before repeating the feat in 1966, a staying power beyond its publisher’s wildest dreams.

One of the books that truly defined the decade, it entrenched itself in the national consciousness in a way similar to Geoffrey Blainey’s The Tyranny of Distance, published two years later, another title that instantly entered the national lexicon.

Blainey’s deeply researched work, which reflected his training as a historian, was tightly argued. In contrast, even Horne admitted that his book was “a collection of snapshots of Australia”. An assemblage of ideas and insights that had been amassing for a decade, Horne thought it was part of the book’s success, handing readers a host of opinionated pages of observation and commentary.

More than the loose structure, though, the book’s style was crucial to its impact. That style came from Horne’s long spell as a journalist, editor and advertising man.

Horne had a keen understanding of what readers wanted to know and talk about. He had spent years honing his approach, addressing Australia’s burgeoning magazine and newspaper readers, and recognised their hunger for a new type of journalism that The Australian sought to embody: urbane, expository, intelligent, sparky, informed.

And if it worked for magazines and papers, why not for a serious – if chronically irreverent – book about who we were and how we now lived?

The Lucky Country introduced this sharp change in tone to Australia in the 1960s, marking it as ineradicably as David Williamson’s plays would do. The content matched the tone, too, aggressively insisting that the way we lived had changed so abruptly that the nation could no longer be served by the standard-issue ideas.

The national mythology, populated by bush legend figures (shearers, bushrangers, drovers) and grizzled Anzacs, had no relevance to daily reality.

Australians were urbanites and suburbanites, and increasingly so: from 1947 to 1966 the percentage of Australian living in cities leapt from 68 per cent to 83 per cent.

Misappropriated and misunderstood

Horne’s coup was to bridge this gap between myth and reality. Certainly to his mind The Lucky Country’s success came from the fact it captured Australia as Australians experienced it, not through the fake lenses of a glorified past.

It was, Horne claimed, the first book to reflect “the suburban nature of the lives of most Australians without jeering at them”. What really cut through, however, was the book’s underlying thesis.

Despite its gadfly-like style, the book worked off a set of powerful assumptions that constituted a strong, even startling, argument.

Horne would complain ever after that its title had been misappropriated and misunderstood. But it is hard to deny that the title itself made the argument palpably clear.

Earlier exercises in self-reflection generally portrayed Australia’s journey to nationhood as a process of maturation. Nurtured under the shelter of Britain’s wing, foresight, hard work and inspired guidance had allowed the infant nation to grow into a strapping adult, capable of standing on its own feet.

Horne knocked that narrative for six. Australia’s prosperity and stability were not, he argued, the result of increasing national maturity, much less diligence and determination. They were due to sheer good fortune. To make things worse, it was a good fortune the country didn’t deserve – or know how to use.

The problem wasn’t the bulk of ordinary Australians, who weren’t a bad lot. It was “the people on top”. Our leaders and elites were second-rate provincial mediocrities who had got stuck in a groove some 50 or 60 years earlier and never budged out of it, even as one generation passed to another and still another.

Premature senility

Thanks to them, the nation was in a time warp, living out a fantasy that bore no relation to its realities – or its challenges.

The proper national metaphor, in Horne’s eyes, was not a maturational shift from boisterous youth to fully fledged adulthood; it was a leap from childhood to premature senility. Without “a radical overthrow and destruction of the prevailing attitudes of most of the nation’s masters” the decades to come would likely witness “a general demoralisation; the nation may become run down, old-fashioned, puzzled, and resentful”.

The radical overthrow and destruction of Australia’s outmoded approach, and the subsequent renewal, could, Horne speculated, possibly come through the rising generation. He was drawn to generational explanations of change, citing Walter Bagehot’s comment that “generally one generation succeeds another almost silently.

But sometimes there is an abrupt change. In that case the affairs of the country are apt to alter much, for good or for evil; sometimes it is ruined, sometimes it becomes more successful, but it hardly ever stays as it was.”

Generational change had salvaged the national project before. The great Australian initiative, when Britain and other outside models of development had been energetically rejected, had emerged in the decades at the turn of the 20th century. This was when a nationalism of mateship represented “the general egalitarian position” that, flecked with Irish anti-English hostility, had formed an explicit contrast to an England of wealth and privilege. To those who had experienced that earlier time, “this present pause would be unbelievable”.

Robert Menzies epitomised everything that had gone wrong. He had absorbed too much of the pro-British obsequiousness of the post-World War I world, notably “the ceremonial clinging to Britain” that was “part of the delusional structure of the people who were running Australia”.

Unable to escape that delusional structure’s grip, subsequent generations had fallen into Menzies’ stride rather than broken it. And while Menzies’ leading rival, Arthur Calwell, could not be accused of being unduly pro-British, he was no better able “to recognise and dramatise the new strategic environment of Australia”.

Fresh start

As a result, “the nation that saw itself in terms of unique hope for a better way of life is becoming reactionary – or its masters are – addicted to the old, conformist” ways of doing things. The inability to cope with change meant the “momentum towards concepts of independent nationhood has slowed down, or stopped”.

There were, however, inklings of a fresh start. Although “still full of mystery”, the generation born during and immediately after the war “seems fresher”. Who knew, “it may be the generation that changes Australia”.

Expressing the egalitarian pragmatism that Horne identified as the quintessential philosophy of the national consciousness, the baby boomers would be socially progressive, tertiary-educated, technocratic pagans and managerially gifted hedonists. As they gained control, the better qualities of the Australian people, sprawling and sunburnt on the nation’s beaches, would finally be able to express themselves unencumbered by the tired leftovers of a bygone era.

Exactly how this revolution would occur was left unclear.

Horne’s career had to this point been on the political right. He was still editor of Quadrant when

The Lucky Country came out, a vigorous anti-communist who had run as a Conservative in an English election while living there in the 1950s.

In some ways, he might still have been a conservative – for example, in his identification of the ideals of egalitarianism and fraternity as the essence of a national culture that needed to be preserved.

What is certain, however, is that by the time of The Lucky Country, Horne was no conservator. His conservativism was what he now described as being of the “radical”, even “anarchist”, variety. Enormous social and political renovation was the order of the day and the book’s task, Horne said, was “to produce ideas that may prompt action at some later time” – but that would need a change agent only the future would disclose.

Whitlam the messiah

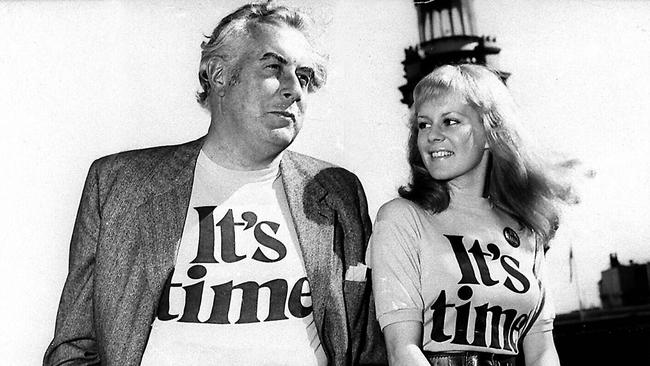

Given that sense of anticipation, it is unsurprising that Horne drank the Gough Whitlam Kool-Aid deeply and early. When Whitlam replaced Calwell as ALP leader, Horne declared that he “seemed to understand that not only the Labor Party but Australia as a whole needed a psychological reorientation, a new tone and style to make it adaptable in the modern world”.

In April 1973, less than six months after the federal election that brought “the ludicrous Menzies era” to a close, Horne predicted that Whitlam could easily become Australia’s greatest prime minister. Until then, it had begun to seem “as if our sense of nationality was going to remain rather grisly: a fairly second-rate European-type society cutting itself off from its environment and from the mainstreams of the age, trying to keep up its spirits by boasting about its material success, its mines and its quarries”.

Now he predicted a new national anthem within 12 months and a republic within 10 years. The eternal “tomorrow” of utopian political vision had suddenly become, as it were, Monday morning – and Whitlam was its messiah.

Inevitably, having soared to such heights, the deflation when the curtains fell on the new dawn was all the more traumatic. It exploded into visceral anger in the book Horne wrote immediately after the 1975 dismissal.

Whitlam, Horne said in Death of the Lucky Country, had been doubly “assassinated” – once by the governor-general, then again “by his defeat in an illegitimately called election, done in by strong and powerful enemies”.

The elites had had their revenge. Public violence, Horne suggested, would be an entirely understandable response. Horne’s own response was unending, incandescent, outrage.

Mingled with bitterness, that outrage pervades everything Horne wrote after Whitlam’s ignominious end: largely second-rate works that have faded from memory. He had, it turned out, only one book in him – but it was, nonetheless, a book of immense importance, not least because of its tough-minded approach to Asia and its adamant rejection of non-alignment as a bastardised form of neutralism.

To say that is not to ignore the paradox that underpins the book. Horne’s discussion in The Lucky Country of Australia’s British inheritance was rich and nuanced. But as the years passed Britishness became a birth flaw to be denounced with ever greater ferocity.

Yet for all of Horne’s strident nationalism, The Lucky Country is redolent, if not derivative, of the Britain of the mid to late ’50s.

During his stint in Britain, Horne had fully absorbed the new concept of “the establishment”, coined by London columnist Henry Fairlie in 1955 to describe not simply the individuals who held and exerted political power but the whole network of institutions, practices and attitudes through which those in or near power maintained their ascendancy.

By 1960, denouncing the dead hand and crippling impact of a musty, hidebound elite had become the stock in trade of an emerging class of British commentators.

Horne brilliantly transposed that leitmotiv to Australia, just as he transposed those commentators’ biting tone and the advertising-influenced writing style of the new American journalism.

But jingles are no substitute for deep analysis – and The Lucky Country’s marvellous hits come amid some disastrous misses.

No miss weighs more greatly, or has had more deleterious consequences, than Horne’s easy, airy dismissal of the extraordinary economic advance Australia had experienced since the ’40s. To describe that achievement as due to blind luck is simply absurd.

It was, in fact, achieved in the face of a world economy profoundly and increasingly adverse to primary exporters, who had to deal with plunging commodity prices, as well as the relatively slow growth, and chronic balance of payments problems, of Britain, which was still Australia’s crucial export market.

That Australia managed to not merely cope with that environment but grow rapidly was no gift of nature: it reflected the remarkable adjustment capability of its primary exporters, who, as well as turning to Asia’s emerging markets, reduced their costs more rapidly than prices were falling.

And it was the adaptiveness of its primary exporters, along with the entrepreneurship of towering giants such as Lang Hancock and Arvi Parbo, that set the foundations for the mining booms Horne derided as just due to luck.

The belief that Australia’s prosperity was the result of good fortune rather than entrepreneurship and aspiration became one of the left’s key illusions. It framed Whitlam’s disastrous economic policies, which assumed the Australian economy was “indestructible”; it has recurred in recent years as successive Labor governments have dismissed mining, low-cost energy and agriculture as mere residues of earlier ages. The blind luck thesis had a natural appeal to the new elites who, in the decades after Whitlam’s fall, committed themselves to the fundamental remaking of Australia.

So did the overestimate of the merits of technocratic bureaucracy and the underestimate of the merits of Australian traditions that permeates Horne’s work. In that respect, Horne was right: the baby boomer generation changed Australia. And it was armed with the Whitlam-Horne vision that its leading scions became the new establishment.

By the late ’80s this new order had almost entirely replaced Horne’s reviled old second-rate elites, taking the commanding heights of cultural institutions and regulatory bodies, as well as dominating acceptable political discourse.

Undoubtedly a classic

Under first the boomers, and then their children’s generation, the longstanding policies, practices, norms and pronouns that had framed Australian life were upended, reversed, junked, repudiated.

In 1964, Horne declared that ordinary Australian people were not the problem: the elites were. Sixty years later that seems truer than at any other time in Australian history, but the elites in question are those whom Horne heralded and championed.

The great irony, though, is that the ordinary suburban Australians Horne brought to the forefront of national conversation have proven the immovable bulwark against which those new elites have collided, as they repeatedly rejected the new establishment’s wishes and projects.

Horne himself may not have appreciated this irony. But he can claim the credit for foretelling the two great protagonists in the national drama that continues to play itself out in the public square.

In the end, it is the hallmark of a classic that it is a book that can be read in a slightly or very different way by each generation, always having something new to say. Set against that test, The Lucky Country is undoubtedly a classic.

For all of its shortcuts and grievous errors, its insights still dazzle, no matter how often they are read or reread. So does its freshness, its sense of humour and perhaps most of all, its eager hopefulness and sense of aspiration.

On this joint birthday of The Lucky Country and of the newspaper that, 60 years ago, launched its career, renewing that spirit remains a task worthy of giants.

Henry Ergas is a columnist with The Australian. Alex McDermott is an independent historian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout