Without innovation in Australia’s economy, political system and policies, our luck will run out

Canberra squabbles and backsliding on policy agendas from one election to the next has defined the years since John Howard’s removal.

Since then, perhaps partly in a misinterpretation of Horne’s words, the notion of the “lucky country” has come to represent Australia as being rich in resources and geopolitical advantages. A nation that has thrived for decades, domestically and on the world stage, essentially because of good fortune.

Is Australia still that lucky country or are we risking our future prosperity, with poor decision-making stifling the nation’s potential? One of the difficulties in assessing Australia’s standing is choosing which countries to compare ourselves with. It is hard to compare Australia with most of our Southeast Asian neighbours, whose experience of colonialism was different to ours. We are a wealthier nation than almost all of our neighbours, certainly in per capita terms.

However, we are not a developing nation, so our gross domestic product growth is considerably slower than that of most of our Asian neighbours, who therefore are catching up.

If we turn to Europe and the Anglosphere, Australia has a similar standard of living to many Western countries, as well as similar political stability. However, our economic growth is stronger and more consistent than many of these nations. Only the pandemic thwarted our run of economic growth without recession, which dated back to 1991.

But comparing ourselves this way ignores the fact levels of immigration in Australia are high by Western standards. Our economic numbers are propped up by high immigration intakes, ensuring recessions are harder to come by.

But it’s a prosperity mirage. If immigration grows the population by more than 1.5 per cent annually, which it consistently does, our economy grows at roughly that same rate automatically. But it’s not a per capita improvement.

Put simply, individual Australians are getting poorer even if the population is growing, unless economic growth remains above the immigration rate.

Avoiding recessions with anaemic economic growth isn’t good enough. Australia’s luck may have run out if our dependence on immigration to avoid technical recessions (for the benefit of politicians only) comes at the expense of congestion, affordable housing and individual standards of living.

To be sure, the natural resources Australia has are an enormous advantage not many other nations have. Even with changing circumstances courtesy of climate change, Australia’s resource abundance extends to rare metals needed for batteries and wind turbines. We have more yellow cake needed for nuclear power than any other nation barring Canada.

Yet unlike similarly resource-rich nations Australia never invested in a sovereign wealth fund to ensure longer-term benefits from the extraction of resources. Norway led by example on this front.

Another reason to be concerned about Australia’s capacity to retain lucky country status is the timidity of the political class in the context of a mass media incapable of supporting bold reform to set up future prosperity. I’m talking about tax reform, federation reform and thinking outside of the box when it comes to ways to modernise our political and policy structures. Although Horne may have been a critic about parts of the Australia he witnessed throughout the 1950s and ’60s, we were more policy innovative back then than we are today.

Of course our acceptance of diversity has improved markedly, as it has in most Western countries, but inventiveness in our national institutions has waned.

Australia was the second nation to give women the right to vote, one of the first to introduce preferential voting and to this day we are one of the only countries to use compulsory voting as a means of ensuring sections of the community aren’t disenfranchised from the democratic process. Our amalgam of British responsible government and American federalism was globally unique. The introduction of proportional representation in the Senate in 1949 was a bold and refreshing reform that led to greater diversity of representation in a check-and-balance second chamber.

Yet our willingness to contemplate ongoing reforms to modernise our voting structures today are limited at best. This is symptomatic of wider reform inertia among politicians.

Perhaps Horne was right and Australia has long been “a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck”. But if he was right then, we have got worse since, if perhaps more lucky as Australia surfed the wave of Chinese economic growth and reliance on our national resources.

The political years that followed Horne’s scathing assessment brought a cultural refit he likely would have approved of when Gough Whitlam (1972-75) elevated the arts and introduced universal healthcare and free higher education. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating (1983-96) addressed some of the economic sustainability issues surrounding the Whitlam reforms, including modernising the economy, which had been a missed opportunity during the Fraser years (1975-83). John Howard (1996-2007) paid down debt but, more important, reformed the tax system and the industrial relations system, extending our luck-in-leadership a little longer.

It has been more than 15 years since the Howard government was defeated, and the back half of that administration was far less impressive than its earlier years.

Canberra squabbles and backsliding on policy agendas from one election to the next has defined the years since Howard’s removal. It has been an unedifying time for both major parties. Indeed, it has been during this period that the use of immigration to prop up national accounts has become all the more pronounced.

So what happens next? In the short term we will have to face up to difficult economic times; slowing growth and rising unemployment. The panacea of high rates of immigration won’t be able to mask the economic challenges at a micro level, even if immigration helps stave off a technical recession at the macro level.

If we don’t face up to the need to continue innovating – the economy, our political system and our policy settings – the national luck we’ve had for so many decades may well run out, leaving this generation to hand over a worse standard of living to the next.

That would represent the ultimate proof that we are no longer the lucky country.

Peter van Onselen is professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

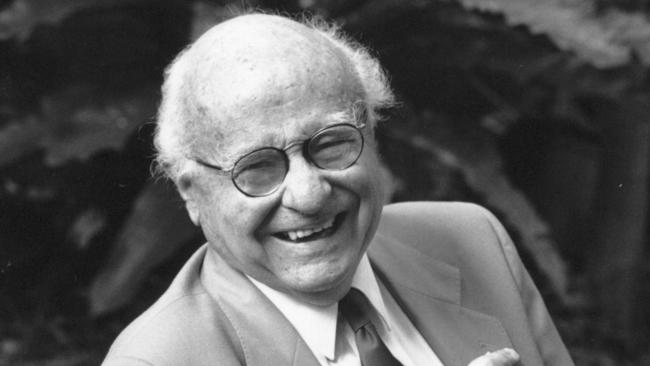

Donald Horne’s 1964 book The Lucky Country was anything but positive. He lamented a lack of culture, ambition and leadership. His argument was that Australia’s rise at the time was despite the country’s citizens and politicians, rather than because of achievements that strengthened the Australian economy and political system.