Six months after the horror, I found solace in Israel’s killing fields

When you step into a place where horrific things happened, the things you think and feel rarely match your expectations.

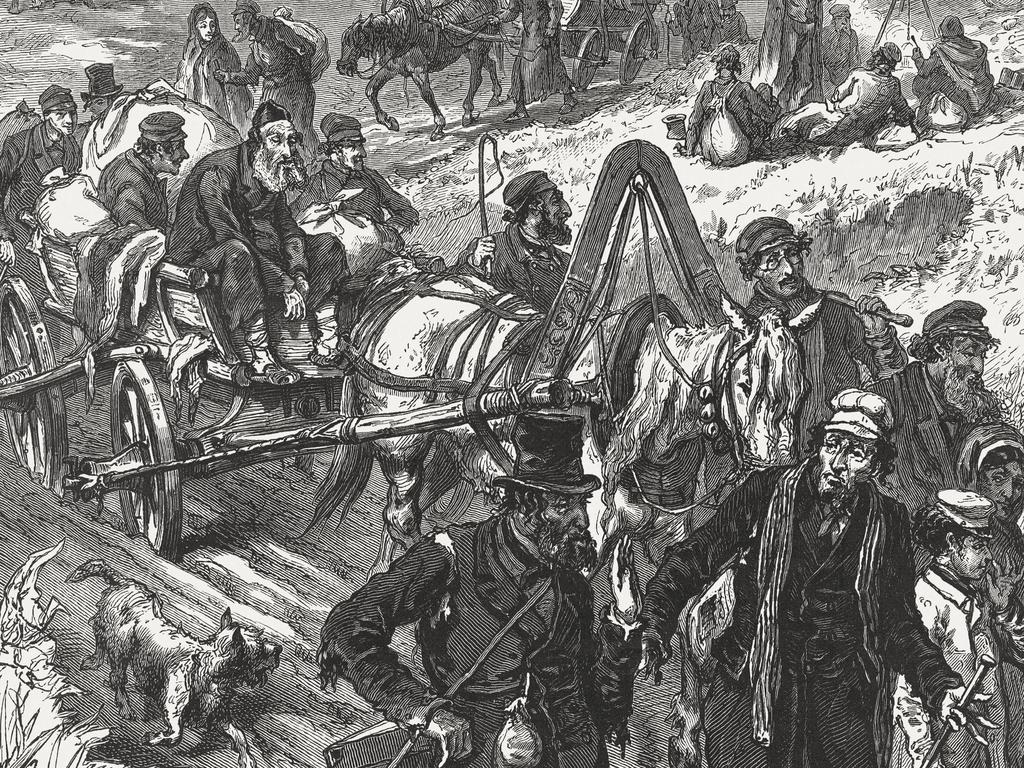

When you step into a place where horrific things happened, the things you think and feel rarely match your expectations. This is something I knew from my experiences of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the killing fields of the former Soviet Union.

At Auschwitz, the preserved apparatus of industrial-scale slaughter, the dark aura of the trees encircling the camp, the sinister look of every store and piece of wire seemed to drag me down, making every step feel crushingly heavy.

In places like the Babi Yar killing site in Kyiv, where tens of thousands of Jews were piled into a ravine and machine-gunned, it was difficult to feel anything in what is now a typical urban green space with nothing to evoke its crimes beyond one’s imagination and the words of poets and historians.

Inspecting the military bases, the towns and agricultural villages in southern Israel that were the scene of Hamas’s atrocities exactly six months ago was an entirely different experience again.

I was led through the villages and communal farms by residents who had just a few months earlier seen their parents or siblings defiled and slaughtered in the very rooms in which we now stood. An officer led me through the blackened carcass of the command room at the Nahal Oz military base where memorial candles marked the spots where female soldiers were burned alive, the unnatural smells of decay still present in the stagnant air.

When I clambered up the steel steps of the observation deck, I could look unaided directly at the strange shapes of ruined buildings of northern Gaza, just a few hundred metres away. Desolate and silent, except for the periodic thuds of artillery, now a monument to the defeat of Hamas and the wrath of Israel.

Despite the closeness and intensity of it all, the feeling that overcame me was one of calm and the images that my mind clung to were of an uncommon beauty. Beauty is everywhere in the south of Israel. Far from the big cities of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa or the highly industrialised major towns up and down the coast, the south reminded me of the NSW south coast with its little birds skipping along the treetops and eucalyptus trees, planted to absorb the moisture of marshes and swamps and create a fertile ecosystem.

When I walked through Kibbutz Be’eri, I could not grasp whose boots had just months before crushed the plant beds I strode past. Instead, I thought about how neglectful a father I must be to raise my children in a metropolis and not in a place like this. It was idyllic. Was.

The field where the Supernova festival took place was the prettiest of all; 364 posters attached to wooden stakes showing the faces of the Israelis murdered there. All strikingly beautiful with characteristics of the Middle East, Europe and Africa from which their families came. The horrors go far beyond the mass of lives taken. Young women were dragged to the trees surrounding the field, tied and pack raped before being executed. Young men had their genitals cut off and shoved in their mouths. First responders found bodies slit open with organs ripped out. And against it all, I see the beauty of the field and the smiling faces of joyful young people.

I was taken through Kibbutz Be’eri by Kinneret, whose sister Galit Carbone was born in Sydney and had emigrated to Israel as a child. As Kinneret and I spoke outside the house her sister was murdered in, another kibbutz resident approached us and sheepishly offered condolences to Kinneret, telling her she sometimes sat with her sister in the kibbutz dining hall and that she took her job as a librarian seriously and didn’t mind complaining now and again.

Kinneret shows me the safe room in which her sister spent her final moments before Hamas fighters broke through and shot her with Kalashnikov rifles.

A few minutes later, I meet a waif of a lad in ill-fitting fatigues. He doesn’t smile as he shakes my hand. On the morning of October 7, he single-handedly engaged the Hamas fighters who had stormed the kibbutz, holding them off for precious minutes to allow families to get to their safe rooms.

He killed five terrorists before running out of ammunition and under heavy fire he picked up the Russian rifle of one of the attackers and proceeded to take out two more.

I insist on hugging him again and again, knowing no other way to convey my gratitude and abiding respect. The middle-aged man beside him also had a story to tell. His son fell in the same battle.

I saw the tiny village of Kisufim where another hero, the village’s head of security, fought a grim battle from the front room of his house, refusing to yield as his wife and children cowered in the safe room behind him. I saw rooms cratered and pockmarked from the grenades thrown in causing him to jump in and out of windows to escape the blasts and dodge the searing shrapnel ball bearings before resuming his defence of his family and his home.

The last resident of Kisufim to be killed was a dairy farmer, Reuven Heinik. He survived the initial massacre and pleaded for army clearance to return to the kibbutz two days later to water his beloved cows. He was shot and killed by a Hamas fighter hiding in a barn on October 9.

In Tel Aviv, I visited wounded soldiers. One young fellow showed no ill effects of combat except for a scar on his cheek and a rigid neck. I learn that he survived a bullet to the face. Another injured soldier, Yuval, a tank commander, tells me how he and his five comrades raced to the scene of the carnage but were immobilised by a strike from a Hamas drone. For hours they battled the Hamas fighters who had crawled on top of and underneath the tank seeking to enter it or incinerate those inside. He wrestled for control of the top hatch with one Hamas fighter, a mortal tug of war, back and forth. He saw the maniacal, bulging eyes of the terrorist and then he saw him go limp and fall from the tank after a sniper shot from an Israeli comrade.

Yuval grows anxious as he talks, he twitches, his voice cracks as he recalls peering out of the tank through a bullet hole watching the terrorists run away as he lay helpless with a crushed and mangled leg that was miraculously spared amputation. The Hamas men head towards the gates of the kibbutz and Yuval can do nothing to stop them.

I met Victor, a squat, rotund, dark-skinned grandfather who re-enlisted in his old unit of paratroopers to fight alongside his son. A few hundred metres from the Gaza border, some civilians had put on a barbecue for the soldiers. I waited anxiously with Victor for his son to meet us there. “Where is he now?” I ask. “Khan Younis.” The son comes out, wearily hugs his old man and sits with me in a plastic chair for a chat. I offer him a cigarette, assuming all soldiers must smoke after battle, but he waves it away in the same way I’d turn down a piece of pie.

I ask him about the battle, about whether war aims are being met, whether Hamas fights to the death or surrenders, what the morale of the Israelis is like, whether he’s surprised by the quality and motivation of the Hamas fighters.

He answers each question assuredly with an economy of words, like I’m interviewing him for a junior manager position at Clint’s Crazy Prices.

The battle was good, successful. They’re meeting all their aims and driving out Hamas, suburb by suburb. Sometimes they surrender, sometimes they have to shoot them. Israeli morale is sky high. Hamas doesn’t fight well. They hide among women and children, and if the fighting gets hot, they drop their guns and run away. Every minute or so we hear the low thud of artillery just hundreds of metres away. Yet I’ve never felt more safe in my life.

Everywhere I go, I see a country affected by war. Even in Tel Aviv, which would party through anything. A barman asks me where I’m from and what brings me to Israel. Solidarity, I say. He tells me he just returned from Gaza.

Suddenly his handsome face grows excited. He begins frantically scrolling through his phone to find a photo. Stripped and captured Hamas fighters? A trophy of war? He shows me a photo of a mongrel dog with that coarse orange fur. “I found her alone in Gaza. A stray. No collar. Now she’s in my apartment.”

It was a moment that showed me that the Israelis knew exactly who they were fighting against and with whom they had no quarrel. I could see the difference between those who fight to defend something and those who fight only to destroy.

That was what the Hamas attacks were all about. Taking something beautiful and mutilating it. It was an acid attack on the face of a hopeful nation. There was no military objective to the attacks. No prospect of gaining territory. Only the certainty of death for those who crossed into Israel and months and months of misery for the civilian population of Gaza.

I hear about old Palestinian men with walking canes entering Israel on the heels of the militants. They came to see the verdant fields and the pretty little houses the Jews had built. And if they couldn’t turn their own territory, their own fields, their own sparkling Mediterranean coastline, their own lives into something beautiful, they were going to make sure the Jews, those cursed children of pigs and monkeys, weren’t beautiful anymore.

They may have briefly satiated a bitter desire to violate and disfigure, but that is the extent of their success. I discovered a national character of such depth that no violence can alter. Soldiers who are the salt of the earth. Humble, dignified, strong. They are just kids, but you feel invincible in their calm and determined presence.

The families of hostages who rise each morning from sleepless nights and remind the world of their excruciating plight. The Hamas leadership thought they could set the region alight, inspire millions to look at their GoPro footage and take up arms, drag their own Jewish women by their hair to slavery, plunder their own kitchen appliances, partake in their own perverted tortures. But they miscalculated.

Their cruelty has left the Palestinians vanquished and adrift with more admirers in the ugly recesses of social media but in few other places. Predictions that Israel’s two million Arab citizens would raise insurrection in the name of Gaza came to nothing. And I miscalculated, too. I came to Israel thinking it needed something from the Jewish world. That it needed to draw on our strength, our resilience, our support. In fact, it is we who need Israel. We need it to show us the way. We need its full hearts that approach its mission with a solemn dignity. We need its quiet confidence that those who build will outlive those who burn. And we need it to show us how to endure tragedy and hardship and emerge with hardened minds and matured souls, and a readiness to fight for as long as necessary.

Alex Ryvchin is the co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout