Hatred of the Jews returns

Jews are not seen as individual human beings but as something dangerous in the eyes of many says Alex Ryvchin, in a disturbing new book tracing the origins of anti-Semitism.

My family left the Soviet Union as refugees when I was three years old. Our eventual freedom, and that of millions of families like mine, was the culmination of a decades-long international campaign under the banner “Let my people go”, which pressured the Soviet government to allow its Jewish population to leave.

As the Australian diplomat Douglas White put it when raising the matter at the UN, “should the USSR find difficulty in according Soviet Jewry full freedom to practise their religion, it has a moral obligation to permit them to leave the country”.

Of course, the Soviet position was that anti-Semitism belonged to the previous regime and any suggestion that the Jewish population faced institutional racism was just Cold War-era mischief making. In reality, Soviet Jews suffered immensely. Their identity papers were marked as “Jewish” regardless of how long families like mine traced their roots in those lands, or how integrated they strove to be.

Aside from having no freedom to practise their faith, Jews were subjected to racial restrictions, including entry quotas into universities, thereby excluding them from certain professions, and a prohibition on Jewish cultural practices including the printing of Hebrew-language publications. No other nationality or ethnic group suffered such measures.

This institutional anti-Semitism began in Tsarist times and had established the Jews as people of no worth, to be ridiculed and discarded. In George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, a retired Russian army officer tells Orwell how in the army it was considered poor form to spit on a Jew “because a Russian officer’s spittle was too precious to be wasted on Jews”.

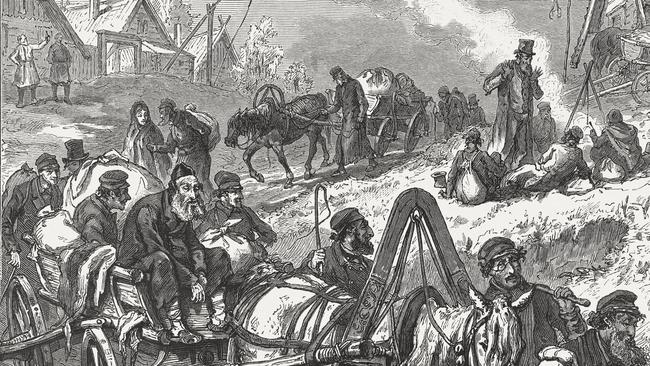

In the 17th century, the Ukrainian nationalist figure Bogdan Chmelnitski and his horsemen unleashed such carnage on Jewish communities that to read the accounts of them leads one to call humanity into question. These crimes set a certain rhythm whereby any upheaval, any discontent, any pursuit of political transformation resulted in Jewish communities being set upon with a perverted delight and with total impunity.

It happened throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries often at the instigation of the authorities. It happened during the civil war that followed the Bolshevik Revolution. And it happened during the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, resulting in 1.5 million Jews disappearing in forest pits and ravines and burning warehouses, through every method of torturous and unnatural death imaginable.

The permanent fear of mob violence and the injustice of racist laws was a fact of life but the vulgarity and public humiliations the Jews experienced in the street, on the trolleybus, in the shop queue, stung bitterly and daily. It was not uncommon for irate citizens standing in futility to buy basic necessities to break out into curses and cries about the Jews. “If there’s no water in the taps, the Jews drank it all,” was one common refrain. “Beat the Jews, save our Russia,” was another. Every Jewish boy had taken regular beatings in the schoolyard. My father’s lunchtime football games would quickly descend into spirited bouts of “catch the Jew”.

My grandmother had once thrown herself upon her elder brother’s prone body to protect him from the boots of anti-Semitic thugs that were striking his ribs and skull. My mother, who lived a block away from a Holocaust-era killing field in Kyiv known as Babi Yar, experienced anti-Semitism like a daily ritual. As her trolleybus approached her destination and the conductor called out, “next stop, Babi Yar,” every day, without fail, one of the drunks dozing peacefully would suddenly return to lucidity, sit bolt upright, and cry out and cackle and lament, “if only they’d shot all you Jews here!”

My father would tell me of how admired he was by his pupils in the town high school where he taught maths and physics. He was a young, dynamic and passionate teacher. Then one day, a rumour circulated the schoolyard, that he, their beloved mentor, was in fact a Jew. The students filed into his office, one by one, to ask if this was really so, and to offer their condolences. “But how could this be?” one boy asked him with great earnestness, “you’re such a good person.”

As a boy, my father had made the mistake of asking one of the old town matriarchs why the area on the edge of the town limits was called a ravine when it was in fact completely flat.

“Ah my boy,” she answered with great pride, “it was a ravine, until we filled it with Jews.”

My father had once asked his father why he kept an axe permanently positioned by the front door. He had never seen it used. His father took a sharp breath, sat his son down and asked him if he knew the word “pogrom”.

Eli Wiesel survived the hellscape of Auschwitz and became a Nobel Laureate. In the 1960s, he travelled to the Soviet Union, including to my birthplace of Kyiv, to see for himself the conditions under which the Jews there lived. He then recorded his observations in a book titled The Jews of Silence. Wiesel wrote that one thing struck him about the Jews there above all others. It was their fear. Fear inhabited the eyes of every Jew he encountered without exception. That fear came from the individual traumas described, some variation of which had been experienced by every Jew. But it also came from a collective panic from opening the papers to see the “rootless cosmopolitans” and “Zionist bankers” denounced, cartoons of great hook-nosed creatures preying upon the decent citizens of the state. Leaving the Soviet Union at the age of three, I of course had no personal experience of any of this but I witnessed this in my parents and grandparents. The fear and trauma are not easily dislodged, not even by the safety and distance of Australia. It presents as a sort of nervous energy, a perpetual sense of looming calamity, a tendency to experience joy as an interval between disasters, and a stiffening of the face the second the word “Jew” is heard.

Aside from some fairly harmless schoolyard run-ins, my childhood was free of anti-Semitism. When it did occur, it was momentarily jarring but mostly left me perplexed. At tennis practice, a boy of no more than 10 once came up to me and said, “Jewish, ewww”. In high school, I regularly heard “Jew” used as a verb, as in “he’s trying to Jew you”. These incidents didn’t scar me or cause undue distress. They were unpleasant, but I had by that point come to understand what real anti-Semitism was, and it was not that.

My family moved house every couple of years as new migrants finding their way tend to do, and in my early teenage years we came to live in a modest apartment block in middle-class Randwick in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Directly above us lived a couple who had migrated from Austria. The man was ageing but tall and vigorous, with a deep resonant voice and a farmer’s build. When he met my father, who spoke with a strong Russian accent and whose pale blue eyes and a fair complexion hardly betray his ethnicity, the neighbour was genial to a fault. He even offered to lend my father any tools he might need to get settled in. Then he saw my mother, and everything changed.

Upon learning that the new occupants were Jews, he would stand on his balcony and bellow at us, night after night, alternating between a thunderous guttural roar and a sneering tone full of menace, “Hitler didn’t finish the job, I will finish it for him”. An evening serenade that continued for weeks. It was plainly terrifying to hear. It became difficult to sleep beneath such a man, and it pained me to see the fear that returned full bore to my parents’ eyes. Why did he hate us so? What did he think we had done? What did he think we intended to do beyond living simple, honest lives as hopeful migrants in a new land?

He surely would have had no coherent answer to these questions. He probably didn’t ponder on them a great deal. But he knew with perfect certainty that the Jew, represented in that moment by my parents and their two boys, was something so loathsome, so repugnant, so inhuman, that he was justified in behaving in such a manner to an ordinary young family.

In many ways, this is the same question that philosophers, historians and social scientists have posed when attempting to make sense of the Holocaust. How did a country as advanced and enlightened as 20th-century Germany make anti-Semitism its national idea, deploying its magnificent energy and full force to pursue every Jew, even those thousands of miles away, until they were nearly obliterated from the face of the Earth? How did many thousands of ordinary people all across Europe choose to join killing squads, volunteer to form search parties to comb the forests, and dispossess, humiliate and murder their neighbours simply because they were Jewish? How did elite soldiers, educated, Church-going men in their 30s, perform actions such as throwing Jewish children into pits of quicksand and hurling sweets at them gaily as they flailed and suffocated before their eyes?

We imagine them carrying out their missions with a robotic efficiency. But accounts of the method of the killings, testimonies of perpetrators, witnesses and survivors, tell a story of revelry, of jolly good sport. One of the few Jews who crawled out of the river of blood that was the Babi Yar killing site, recalled the soldiers “laughing as if they were watching a circus act.”

Thousands of Ukrainians, Belarussians and Balts volunteered to join killing squads or for special assignment at the death camps. “Trawniki men,” they were called. They tended to parade around the camps, mocking the Jews standing in line for the gas chambers, driving rifle butts through unassuming skulls, purely for the thrill of it. In Kaunas, the Jews were paraded in a carpark as a young Lithuanian man bludgeoned Jews to death with a crowbar in front of a crowd that sang the national anthem and cheered every killing. The standard defence of following orders just doesn’t seem to do.

They were sleuths and game hunters all at once. They carried out their work with an almost majestic efficiency, sending back daily reports of their accomplishments: 875 Jewish girls and women shot in Berdichev; 90 Jewish children shot in Bila Tserkva; 33,771 in Kyiv; 23,600 in Kamenets-Podolsk.

The answer to why many thousands of fairly unremarkable people, of different nations, professions, languages, religious sects, social classes, each devotedly carried out these acts lies in the cumulative effect of two millennia of conspiracy theories that explicitly bound the Jews up with every evil in our world – money, war, disease, trickery, arrogance, bloodthirstiness, even the killing of God.

The most common explanation for anti-Semitism is that it comes from jealousy for Jewish success. Jews are perceived to be uniformly wealthy and successful – itself a problematic formulation – and Jews have made considerable contributions to innumerable disciplines and fields. Beyond the writers, the Nobel laureates and the scientists is an altogether more impressive achievement by the Jews: their survival.

They have also survived from antiquity to modernity virtually unchanged in their national and religious customs. They have outlived the empires and war machines that sought to annihilate them. They have done so despite the hatred of the Jews being patently unique. There is the longevity of it. The ubiquity of it. The fanaticism of it. The tenacity of it, leaching on to a religion, then seizing on ethnicity, race, community, and finally the nation-state.

All other forms of racism perceive the target group as inferior and treat them accordingly. Slavery, the reduction of humans to chattels, is based on the belief that superior races have the right to possess and exploit inferior ones. Colonialism, even practised benevolently, is the product of a belief system that holds some races to be incapable of self-government. The exclusion of certain groups from professions, schools and social networks is derived from a feeling that members of that group would diminish those places.

The Jew is viewed entirely differently. He or she is not hated because of ignorant aversions to skin colour or other physical attributes – such prejudices are so base and absurd that there is hope they can eventually be outgrown. The Jew is hated for something much more penetrating and elemental. The Jew is hated because of how he or she is perceived to think. This is not easily dislodged. The Jew is given a cunning malevolence, a capacity to trick and deceive. They are given a superior intellect but one that is perverse and drawn astray by dark forces.

This transforms the Jew from an individual human being, bound, often extremely loosely, to other Jews by ancestral, cultural, religious associations, possessing all of the flaws and virtues with which each person is endowed, into something that is at once vastly inferior and terrifyingly dangerous.

In other words, vermin. And as the Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer said, “one does not argue with vermin”.

The crimes of our time occur through this same well-honed process. One October morning in 2018, a man named Robert Bowers, a frequent poster of standard white supremacist fare on social media, entered the Tree of Life Synagogue in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh during the Sabbath service, armed with a semi-automatic rifle. Bowers took his aim and shot 11 Jews dead.

Who were the people he shot? Rose Mallinger, 97 years old. Jerry Rabinowitz, a doctor who treated AIDS patients during the height of the epidemic. Cecil and David Rosenthal, brothers with intellectual disabilities, who were inseparable and never missed a service. David Stein, 71, who had just become a grandfather. Richard Gottfried, a dentist who had sought solace in his faith following the death of his father.

Joyce Fienberg, a retired research specialist. Melvin Wax, 88, a retired accountant who loved the Pittsburgh Pirates. Sylvan and Bernice Simon, killed in the same synagogue they were married in more than 60 years before.

Very many books and articles have speculated as to the question of “why?” Why have the Jews been so despised and so brutalised throughout history? “Why” is a necessary and logical question. Hannah Arendt believed that the Jew is a convenient scapegoat who has suffered from totalitarianism, but it could just as easily have happened to any other ethnic group. Maybe it could have, but it didn’t. It happened to Jews.

Alex Ryvchin is co-chief executive of Executive Council of Australian Jewry. This essay is extracted from his new book, The 7 Deadly Myths, Antisemitism From The Time Of Christ to Kanye West, out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout