Scott Morrison’s secret ego trip has damaged the Liberal brand

The former PM’s secret accumulation of portfolios has wide repercussions.

The ironic aspect of Morrison’s secret accumulation of portfolios is that had this week’s revelations come late last year it is difficult to see how he could have survived as prime minister given the anger of his colleagues and greater stakes for a Coalition that would still have been in government.

The damage to the Liberal Party is palpable.

The Liberals are supposed to be the party of principled government and respect for institutions. But Morrison embarked on an untenable and deceptive accumulation of power. Can you imagine Robert Menzies secretly commissioning himself into five extra portfolios without telling most of the ministers?

The real damage to Morrison comes from his own side – his current and former colleagues who are dismayed, angry and bewildered. The three previous Liberal prime ministers – John Howard, Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull – have criticised Morrison in different ways along with current Liberal leader Peter Dutton, who has had no option but to brand Morrison’s actions as the “wrong call”.

Anthony Albanese has been handed a gift, an instrument to trash the Liberal governing brand. While Morrison is the focus of his assault, Albanese’s aim is to discredit this period of Liberal rule as based in secrecy, deception and impropriety. The conundrum is that the Liberals, resentful at Albanese’s motives, fuel his efforts because they are justifiably aggrieved at Morrison’s behaviour.

By midweek Dutton, recognising party and public sentiment, said: “Scott, obviously, has done the wrong thing here. It’s certainly not something I would do if I was prime minister … I can understand why many of my colleagues are upset and aggrieved.” Dutton said it was a serious error of judgment but he saw no illegality – a widespread assessment.

Interviewed by Inquirer, Howard criticised Morrison but put the crisis in context. “I don’t think he (Morrison) should have done it,” Howard said. “It’s not something, in retrospect, that I can see the reasons for doing it. Morrison, obviously, should have told the ministers who were being doubled up what he was doing. It’s unusual. But it’s not a constitutional crisis and we shouldn’t allow the Labor Party to paint it as such.”

The Prime Minister has engaged in political overkill all week. In practical terms there was no “shadow government”, as he claimed. His assertion that the entire cabinet acquiesced in Morrison’s multi-portfolio model is wrong since most of the cabinet knew nothing about it. His drawing of a parallel with the fight for democracy in Ukraine, highlighting that “democracy is in retreat worldwide”, will delight the converted but is ludicrous overreach.

The relationship between Morrison and several senior colleagues such as former deputy leader Josh Frydenberg won’t be the same again. The claims by some observers of “nothing to see here because nothing happened” are fatuous. A lot happened. Ministerial trust and mutual respect between the prime minister and his ministers are the essence of effective government. Without them, governments fail. Governments are flesh and blood, not impersonal machines.

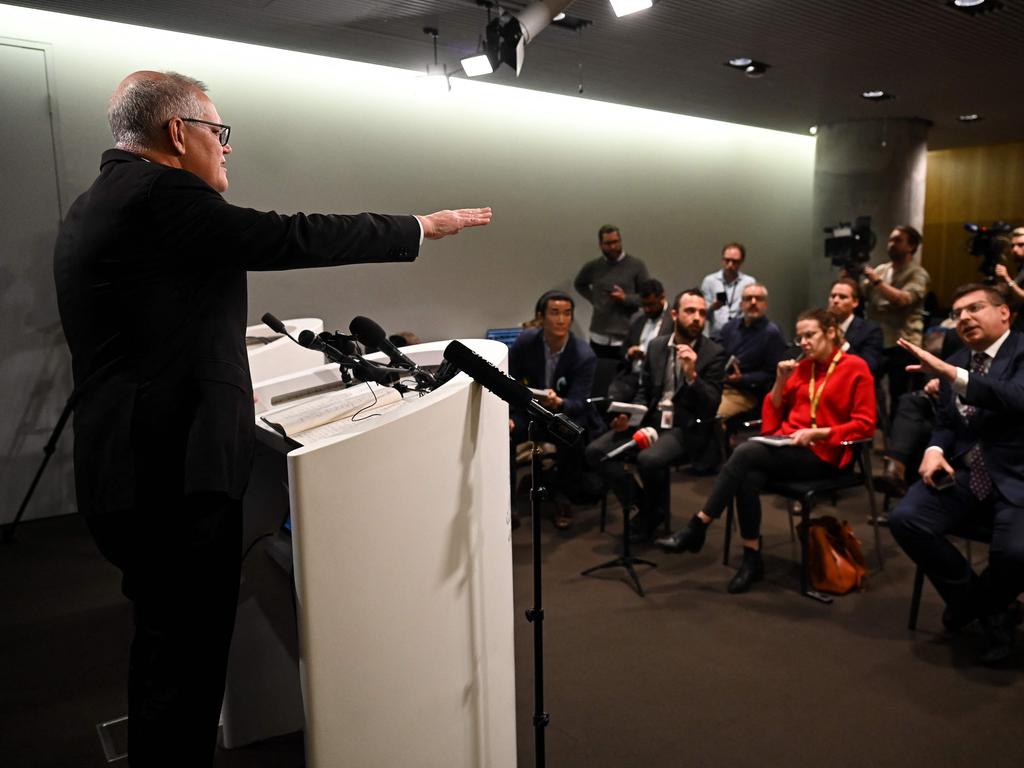

The further problem is that at his Wednesday hour-long media conference Morrison failed to offer a convincing explanation for his actions. Morrison has apologised in person to Frydenberg for commissioning himself as treasurer from May 6 last year onwards and not telling Frydenberg but the damage is done – Frydenberg is angry, believes Morrison should never have done this and that he was under an obligation to inform his treasurer anyway.

Imagine if these revelations had broken before the election. Frydenberg must inevitably speculate that if Morrison’s actions had become public amid dramatic upheaval then Frydenberg might have ended up leading the Liberals to the election and, with Morrison’s removal, would probably have retained his seat of Kooyong.

But this story has a double edge. Dutton can argue it reveals a government incapable of a new politics or solving the immense economic problems it faces. Howard offers the leading line on Albanese: “I think he needs to avoid continuing as an opposition leader and get on with governing. He did win the election.”

And Morrison lost the election. He is yesterday’s man and his legacy will be damaged further. But if the Solicitor-General finds no illegality and if, as Morrison said, he made only one decision – on resources – the wash-up may be that Morrison engaged in an unprecedented, secret and unacceptable use of prime ministerial power that must not be repeated but an activity where no harm was done to any member of the public.

The issue is integrity and propriety, not cost of living or jobs.

Morrison’s defiance this week offers an insight into his psychology and political character. He felt full and personal responsibility for the struggle against the virus, saying the public and the media put the onus on him “pretty much for every single thing” and “every drop of rain, every strain of the virus, everything that occurred”. This is how he responded as PM.

The Simon Benson-Geoff Chambers book Plagued talks of a prime minister lying awake at 3am staring at the ceiling, wresting with the crisis, obsessed about sovereign capability, running a JobKeeper program that meant temporary nationalisation of the private sector wage system. Morrison saw himself governing in a unique way where what counted were results – hence the authors write Morrison operated as a leader “unchained from orthodoxy, ideologically uninhibited and politically licensed to employ dramatic fiscal intervention as leader of a conservative party”.

This was a leader focused on ends, not means. Conventions were being put to the bonfire. Morrison was a prime minister ready to break rules and norms to get the results he needed.

He delivered AUKUS at the cost of misleading French President Emmanuel Macron; in March 2020 he threatened the banks that if they didn’t pass on the full cut in the cash rate he would increase the bank levy in retaliation; confronting economic coercion from China he urged his ministers to intensify their public attacks on Beijing.

But when Morrison this week had to explain the means he used his mood was defiance and his logic was faulty. “You’re standing on the shore after the fact,” Morrison told the media. “I was steering the ship in the middle of the tempest.” Only he could understand the weight of responsibility “that was on my shoulders and no one else.” Yet a pandemic crisis offers no blanket justification for every prime ministerial action – indeed, a crisis demands a higher quality and judgment from prime ministerial decisions.

This is where the extra portfolio commissioning became a fiasco. Already equipped with immense powers, Morrison decided that he wanted more. Seeking concurrent powers as PM with another five portfolios – while the relevant ministers remained in place – has no precedent in our ministerial history. It was a bizarre and inept innovation likely only to cause trouble.

This is precisely what happened – for Morrison, his cabinet, relations with the Nationals and with public opinion while also raising questions for the Governor-General, David Hurley. It was to Morrison’s good fortune these arrangements were discovered only after the election and, in a supreme irony, as a result of the briefings he provided journalists for the book Plagued.

Morrison should have been advised against these arrangements by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. If this did not occur it is a condemnation of the department and its government branch.

There was, however, an argument for this model in March 2020 in relation to health, the first decision, done in collaboration with health minister Greg Hunt and attorney-general Christian Porter once the government knew it might need to invoke emergency provisions of the Biosecurity Act. These provisions were extreme. Vested in the health ministers they gave Hunt wartime equivalent powers beyond review and he likened them “to the divine rights of kings”.

The act should never have been passed in this form. Morrison wanted stronger safeguards in the public interest. The scheme they devised was for Morrison also to be sworn as health minister. Porter advised the power could not be delegated to the cabinet and could only reside with the health minister – hence they felt it was an elegant solution.

Hunt was fully supportive. Morrison briefed the national security committee of cabinet on the decision. Nobody complained. Yet there was no public announcement – and this was a defect. The arrangement was highly unusual at a highly unusual time. The public should have been informed, the arrangement would have been readily accepted. Given the purpose was to safeguard the public, a public announcement was logical. Yet secrecy prevailed.

Porter’s advice that Morrison could also be commissioned as health minister was strictly a one-off, specific to this situation. But Morrison, it seems, applied the advice on four subsequent occasions. A few weeks later he applied it to finance – yet, incredibly, Morrison did not speak directly to Mathias Cormann and he never informed Frydenberg when he commissioned himself as finance minister.

The point is that Morrison had this power. Ministerial appointments are the prerogative of the prime minister, not the cabinet. They don’t go to the Federal Executive Council for authorisation. As far as we know the process was as follows: Morrison got written advice from his department; he then wrote to the Governor-General advising the appointment; and the Governor-General signed the ministerial instrument. There was no swearing-in ceremony.

If these documents are released by Albanese this saga will likely take another, damaging twist.

From this point onwards Morrison’s reliance on the pandemic as justification for his actions falls apart. Nearly a year later in April 2021 he was commissioned as industry, science, energy and resources minister and subsequently took what Morrison says was his only decision in these additional capacities – he stopped a petroleum exploration permit (PEP-11) off the NSW coast from proceeding to protect sitting Liberal MPs. The media statement on December 16 last year was made by Morrison along with four sitting Liberals, all of whom lost their seats at the election in May this year.

The point here is that the resources minister, Keith Pitt, a Nationals MP, had the opposite view to Morrison. Again, this was not a cabinet decision but a decision for the minister. The situation is that Morrison as resources minister overruled the resources minister. Presumably he felt this was the neatest solution given he wanted to avoid an internal political brawl.

This week Nationals Senate leader Bridget McKenzie accused Morrison of “complete disrespect” for the second party of government and claimed his actions “breached the Coalition agreement”. In announcing this decision Morrison did not reveal the full story about the capacity in which he acted. He defended his decision as being in the national interest. Obviously, it had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Finally, in May last year Morrison commissioned himself into the portfolios of Treasury and also home affairs held by Karen Andrews. Morrison is at his weakest in explaining this step. He said he selected those portfolios because these ministers exercised particular ministerial discretions. He called these arrangements a “safeguard” and “break glass in case of emergency” but declined to inform the ministers.

“I did not consider it was likely that it would be necessary to exercise powers in these areas,” Morrison said. Well, why do it? What was the purpose? Asked why he didn’t tell the ministers, Morrison said he didn’t want the ministers to be “second-guessing” themselves or to create the appearance of “a right of appeal” or to have “any diminishing of their authority”.

In short, Morrison felt the arrangement worked only because it was secret. If made public, then it wouldn’t work. But if made public at the outset, surely Frydenberg and Andrews wouldn’t have accepted it anyway or would have provoked a dispute that made the whole thing untenable.

Morrison justified himself this week saying he never interfered with the administration of these departments – another argument for this move being unnecessary.

These May 2021 arrangements delivered no benefits whatsoever but, when revealed, were guaranteed to damage Morrison, his government and his relations with his former colleagues. It was a self-defeating project. Yet Morrison’s approach to these arrangements seems to have been remarkably casual. He said this week he had not recollected these May 2021 decisions – this suggests they seemed unimportant. Albanese scoffed. He asked: how could Morrison not remember?

The bottom line here goes to Morrison’s sense of power. His instinct to concentrate power was accentuated by the pandemic. Convinced of his own judgment, the focus of government decision-making revolved around himself and his office while the cabinet declined as an effective decision-making instrument.

The long-run historical judgment will acknowledge Morrison’s remarkable achievement in protecting Australians from the health and economic consequences of the virus but the way he did this – the means – will be subject to serious criticism.

After talking of betrayal, Andrews this week called on Morrison to quit the parliament. There is no justification for this. The last thing the Liberals need now is a by-election. Morrison loyalist Stuart Robert made the obvious point, saying if Morrison had brought the issue to cabinet “colleagues would have said it’s not needed”. Precisely, the problem is a misuse of prime ministerial power.

Speaking from overseas a mystified but restrained Abbott called it unusual, unorthodox and strange. Turnbull, typically, went into denunciation mode – branding it “sinister” and saying Albanese’s remarks were “absolutely correct”. Turnbull fingered the wider ramifications, saying he was “even more amazed” the Governor-General had agreed.

Speaking in Seoul last month, Morrison said: “One of the most important rules in managing a crisis as leader is recognising that you are not always, if ever, the smartest person in the room.” He said the responsibility on the leader “should not be confused with wanting to be personally hands on in implementing all aspects of your response. That is a recipe for disaster.”

Well said.

Scott Morrison’s mistake as prime minister was his failure to recognise that means can be more important than ends – Morrison had stellar results protecting Australia’s health and economy from the pandemic but his actions undermined democratic principle, public trust and cabinet government.