Russia’s dam busters have landed a generational hit on Ukraine

We do not know yet the human cost of the bombing of the Kakhovka Dam, but history shows that such events have vast consequences.

It has been a while since a dam was destroyed in an act of war. The evidence points to Russia mining the Kakhovka Dam that holds back more than 2000km of the mighty Dnipro River.

While the death count remains low – it is difficult to tally in a theatre of war, but likely to rise sharply – the dam collapse is a disaster, already flooding, to an average depth of 5m or more, 600sq km of Ukraine’s Kherson region. It has destroyed industry and vast tracts of farmland along with ancient buildings and town squares, while 14,000 families have lost their homes.

Swept downstream are the dead, many thousands of farm animals, tonnes of agricultural chemicals including pesticides, the contents of flooded septic systems and Russian-made and laid landmines.

If, as looks likely given intercepted communication in the region, this was Russia’s plan, then it has struck a generational blow to southeastern Ukraine. Other than destroying the dam wall that may have given Ukraine access to eastern banks of the Dnipro – both sides are Ukrainian – it is hard to see how Russia benefits strategically from the vandalism, other than to cause long-term pain for Ukrainians well after this conflict is over.

President Volodymyr Zelensky warned from Kyiv as early as October 20 that Russia, which had seized the dam and its hydro-electric power station early in its illegal war against Ukraine, already had mined it. The dam and power stations became hostages of sorts that even a retreating Russian army might easily execute.

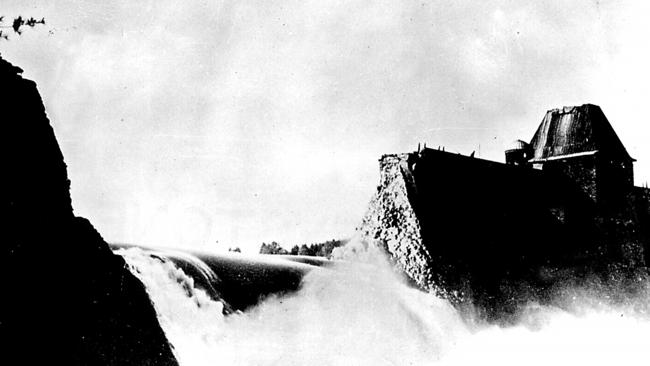

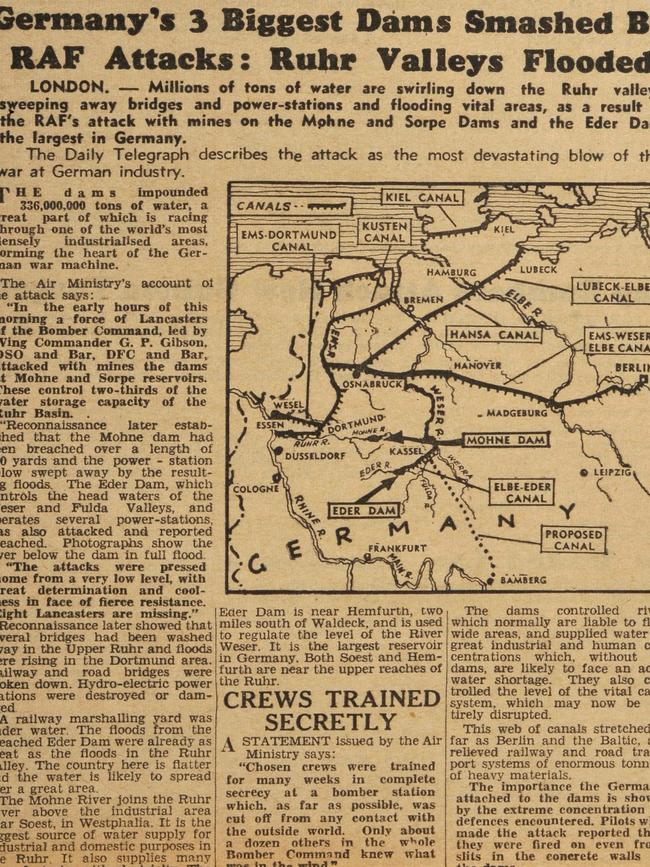

Ironically, the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam occurred almost precisely on the 80th anniversary of the most famous dam attacks of all – the celebrated Dam Busters’ raids on May 17, 1943 that smashed the Mohne and Edersee dams, flooding the Ruhr and Eder valleys.

The plan then was to do great damage to the industries that had grown up around the guaranteed supplies of clean water and cheap hydroelectricity, and it worked, although the Germans were able to substantially repair the water storages in about four months. But the production of steel, reduced by three-quarters by the raids, was never fully restored.

The brave flyers – 56 crewmen were lost – and the ingenuity of engineer Barnes Wallis, who came up with the idea of backward-spinning, bouncing cylindrical bombs to overcome the netting placed across the dams to prevent attacks, were acclaimed in the 1955 film The Dam Busters. It remains the most popular British film about World War II and its stirring Dam Busters March theme music can be hummed by most people of a certain age.

But legendary journalist and historian Max Hastings published a book on those events four years ago that casts a different light on the swashbuckling tale of victory.

He told London’s The Times in 2019 that among the reasons he wrote Chastise: The Dam Busters Story 1943, was that “in the 60-odd years since I first saw the movie, I have come to understand how much we then believed, which was wrong. The dams raid killed up to 1400 people – more civilian deaths than had been generated by any previous RAF attack on Germany.

“At least half were not Hitler’s people, instead his foreign slaves, almost all women, drowned in the biblical flood – the Mohnekatastrophe, as Germans call it – unleashed by the bouncing bombs. It is fascinating that Guy Gibson afterwards reflected uneasily about this, as his senior officers never did, writing in 1944: ‘The fact that people … might drown had not occurred to us … No one likes mass slaughter and we did not like being the authors of it’.”

Wing Commander Gibson, as first commanding officer of the Dam Busters squadron, was awarded a Victoria Cross, met the king and months later toured the US and Canada with British prime minister Winston Churchill to give a series of addresses about the episode. In Los Angeles he met filmmaker Howard Hawks, who had already employed author Roald Dahl to write a script about Gibson and his men.

Gibson was killed, aged just 26, over The Netherlands the following year limping home in a damaged plane after a botched bombing raid on Bremen, an industrial hub of Germany’s north.

It took many years for people to doubt the Dam Busters’ achievements and for questions to be asked about the morality of the raids. It wasn’t just the civilian deaths; the ensuing floods killed untold numbers of farm animals, especially vital during wartime, and farming land was unproductive long after the war ended.

The fact is you cannot accurately forecast the fallout from breaching a dam that size.

Dams fail regularly, but mostly as the result of human error, sometimes combined with uncommon weather. Indeed, in terms of human lives lost, hydroelectricity is the most expensive form of power generation.

In 1975, just such a correlation of unpredictable weather and human failure led to the world’s worst dam collapse, and the greatest man-made loss of life in a single accident. In the first week of August that year, powerful Typhoon Nina swept across The Philippines and Taiwan and, although it had lost energy by the time it settled over central China, in Henan province it dumped rain not recorded there before or since.

The country’s dam-building splurge had been based in Henan and the giant at the centre of this system was called the Banqiao Dam. It had been under construction since 1951, originally overseen by experts from the Soviet Union. Later, local hydrologist Chen Xing would help build Banqiao, but he had reservation about the size of the projects, the number of sluice gates that had been deleted to save costs, and the level to which the local water table would rise. He was seen as being unnecessarily critical and sacked. He was invited back to the project, raised more doubts, and was sacked a second time. The dams were part of the Communist Party’s ambitious Great Leap Forward and doubters were scorned.

Typhoon Nina’s historic downpours – a metre of water in three days – proved Xing right and about 1am on August 9, just as the clouds cleared and the moon reflected on the now peaking Ru River, those working desperately to sandbag its banks heard a loud bang – one of the workers, an older woman, shouted “The river dragon has come” – the earth cracked open and the Banqiao collapsed. Unknown to those workers, a dam above the Banqiao had failed 30 minutes earlier. Dams beneath it then collapsed like a house of cards as a wall of water 6m high and 12km wide ran through the low-lying areas at 50kmh. This surge inundated 12,000sq km. It is estimated 13,000 people were drowned and that number again swept to their deaths. In one commune, 9600 people, almost the entire population, were killed. About 6 million houses were destroyed. In the disease epidemics and famine that followed, up to 250,000 people died, but news of much of it was kept quiet. It was 30 years before an accurate account of the technological failure, and lives lost, was published.

The Chinese government is reported to have estimated 40,000 dams built at that time are at risk of collapse.

On October 9, 1963, the village of Longarone in northern Italy was physically wiped from the map when 260 million cubic metres of rock and mud from Mont Toc fell into the almost finished Vajont Dam. The wave that followed cleared the 262m-high dam wall by 100m and fell into the village below, killing 94 per cent of its people, including 460 children. All up, 3700 people died that night. The locals had warned for years that Mont Toc talked to them – warning of impending disaster by groaning at night when huge shards of rock and limestone collapsed into the dam as it became waterlogged. Three men, including the president of the company that built it and the chairman of Italy’s Public Works Department, were jailed.

At the time both Vajont and Banqiao dams were being built, Indians were celebrating the completion of the Machchhu Dam in the dry state of Gujarat. It would supply much needed irrigation water for the region’s farmers. The water was held back by an earth-filled embankment engineers believed would withstand the state’s short monsoon season from July. In the 1979 season record rains flooded the area above it and the wall collapsed, killing up to 25,000 villagers below. Until the truth of Banqiao was published in 2005, this was listed as the deadliest dam collapse in history.

Australia has been saved from such dramatic dam failures, but as The Australian revealed in 2012, the mismanagement of Brisbane’s Wivenhoe Dam, Australia’s biggest, contributed to the record flooding of southeast Queensland the year before, which claimed 35 lives, flooded 33,000 properties and caused more than $5bn in damage.

The bombing of the Kakhovka Dam is perversely different. On Friday, Ukrainian flood victims and would-be rescuers were fired upon by Russians who reportedly also shelled evacuation routes. At the same time, Russian troops on the east bank of the Dnipro were reported to have made no attempt to save anyone, even Russian speakers they claim to have liberated. Ukraine’s prosecutor-general’s office has launched a war crimes investigation into these attacks that killed one innocent and wounded seven others.

Russia has installed a “governor” of occupied Kherson, Vladimir Saldo, a collaborator who, ironically, has a degree in industrial and civil construction

He said at the weekend the dam’s destruction had given his bosses in Moscow a “tactical advantage” by tying up Ukraine’s military in rescue efforts and making more difficult waterborne assaults should Kyiv mount a counteroffensive in the area.

Zelensky, who visited the region on Thursday, said his country would not know the full cost of the dam attack until the waters had subsided.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout