Rodriguez’s career was revived in Australia – a concrete Cold Fact

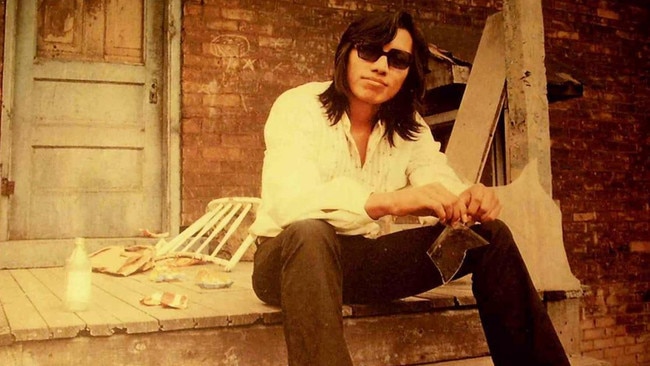

Sixto Rodriguez sang powerful songs of social decay and lives lost to big city squalor and crime – they were unforgettable, but the world quickly forgot him.

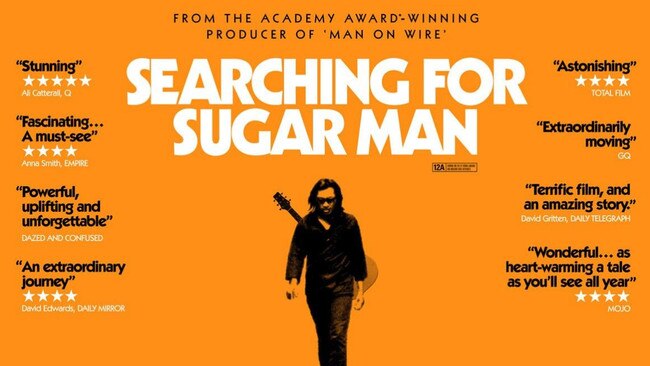

It is curious that reports of the death of the Mexican-American artist date his career rebirth to 2012 and the release of the Academy Award-winning South African documentary Looking for Sugar Man. By then, Nelson Mandela had been the country’s first black president for five years starting in 1994 and had retired. His no-longer apartheid country had long been welcomed back to the civilised world. In 2012, it was recorded that 2.4 billion people were connected to the internet.

So how was it that a group of South African music fans was so unaware of the fortunes of Sixto Rodriguez that they believed he had shot himself years before, after his first two albums failed to chart? And that their enthusiasm sparked a documentary whose makers vowed to track Rodriguez down – were he still among us.

In these sparsely populated ends of the Earth, Australians have always understood it pays to be worldly, to look out on our planet with interest because so much that is going on out there might never make it to our shores. These days the internet guarantees all of it, good and bad, will arrive.

The chaos theory that emerged in the early 1960s included the notion that a small, seemingly irrelevant event could have dramatic repercussions; the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Bermuda might lead to a hurricane in Florida.

The butterfly wings that flapped to revive the lost career of Rodriguez did so in that cluster of in-crowd record shops in Melbourne in the mid-1970s.

At Gaslight Records there was a thin but regular stream of customers seeking the Rodriguez album Cold Fact. At one point in late 1976, Melbourne radio station 3XY announced that 200 copies from South Africa had been delivered to a record shop near Swinburne University. By the time I arrived just after midday they were gone.

Rodriguez recorded just Cold Fact (1969) and Coming From Reality (1970). He waited for other songs to come, but they didn’t and the ’70s moved on without him.

They were hardly recorded anonymously: legendary Motown guitarist Dennis Coffey, who can be heard on dozens of hits including Edwin Starr’s War, Freda Payne’s Band of Gold and The Supremes’ Someday We’ll Be Together, oversaw the first. Chris Spedding – who recorded with Paul McCartney and Bryan Ferry, and produced the first Sex Pistols sessions – worked on the second.

The songs of social decay, drugs and hopelessness on the bad sides of big cities should have fitted snugly with the brief singer-songwriter era then in blood. But they were lost.

Rodriguez was the sixth son in a big family of poor but socially aware workers helping fire the furnaces of Motor City industries. The little-known singer campaigned on city issues and ran for mayor and the state legislature while studying philosophy at Wayne State University.

In June 1977 a small Melbourne record company, Blue Goose Music, licensed his music and issued the album At His Best, which included three unreleased songs. By the time it made it record of the year, its songs could sometimes be heard on radio.

The Rodriguez fan club grew across Australia and by March 1980 he was touring here for the first time with a mix of Detroit musicians and some locals including Melbourne’s Steve Cooney. (Cooney would move to Ireland, record with The Chieftains and Clannad, and marry Sinead O’Connor.)

The shows were low-key, and unforgettably powerful. In Adelaide, Rodriguez walked on in a camel suit with a pale blue shirt and a wad of papers he placed on a stand – his lyrics for the songs he had not sung in so long.

The Melbourne show was recorded and released in time for his second tour in 1981, on which he sometimes supported Midnight Oil. He played Perth on both tours, but the almost 40,000 South Africans living there must have decided to keep it from the relatives back home.

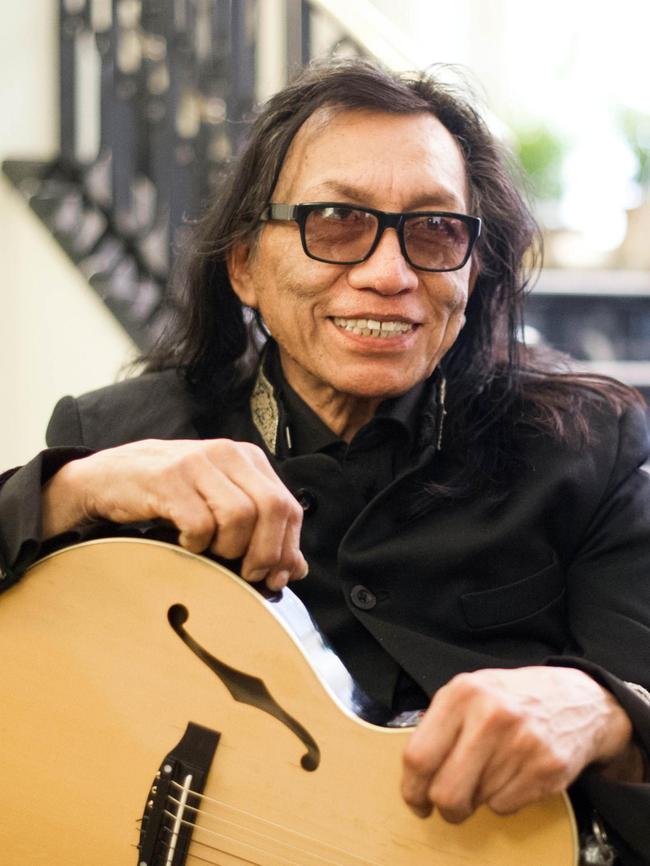

He returned here in 2007 and I finally spoke to him (mates had tried to link us up in Detroit in 1981 but Rodriguez never used a phone and neither could we find the Sugar Man, 33 years before the film).

He told me how much he believed he owed Australia. “The 1979 tour was the highlight of my (music) life until that point – it was so exciting.” He said that on returning to Detroit he became a fan of all things Australian, attending performances by Australian dance companies and going to see Midnight Oil, of course.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout