Republican National Convention: Turning down the heat under cauldron of political discord

American flags are suddenly flying from cars in heavy Democratic areas. These may merely signify a short-term surge of sympathy, but there is a tension boiling just below the surface.

The attempted murder of Donald Trump indicates not only a string of failures (or worse) by his security team but also a nation on a knife-edge as a divisive election campaign enters its final months.

Even in the deep-blue district where I live, in a Rocky Mountain state that has not voted for a Republican president in 20 years, a remarkable number of “Trump 2024” flags are suddenly flying from houses and cars. These may merely signify a short-term surge of sympathy or grudging respect for the former president’s steadiness under fire. But the reaction also reflects a tension, boiling just below the surface, that could break out at any time.

Initial reports suggest Trump turned his head a split-second before the shooter’s bullet struck him so it passed through his ear rather than his skull, missing his brain by millimetres. Both he and the nation may have dodged a bullet, given the likelihood of severe civil unrest, or worse, had Trump been assassinated.

This was clearly in President Joe Biden’s mind as he responded that evening, twice calling Trump by his first name and claiming to be “grateful” that he was safe. The next day, from the Oval Office, Biden called on Americans to “lower the temperature in our politics”, saying “we are not enemies”. Biden or, more likely, his speechwriter may have been echoing Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.” When Lincoln spoke those words, on March 4, 1861, the opening shots of the civil war lay only five weeks in the future.

In his Oval Office address, Biden claimed that violence has no place in American politics, that “this is not who we are”. This, of course, is not strictly true.

Since Lincoln’s murder in 1865 there have been at least eight further assassination attempts against American presidents, three of which also succeeded. In 1963-81 (a period bookended by the murder of John F. Kennedy and the non-fatal shooting of Ronald Reagan), Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were both murdered, presidential candidate George Wallace was paralysed by an attacker’s bullet, there were two shooting attempts against Gerald Ford and a hijacker tried to fly an airliner into the White House to assassinate Richard Nixon.

As Bryan Burrough notes in his 2015 book Days of Rage, during a single 18-month period in 1971-72 the FBI reported 2500 terrorist bombings on US soil, more than five a day.

Biden himself entered office after months of nationwide rioting and political violence that left 26 people dead and hundreds injured, and cost billions in property damage. He was inaugurated behind a barrier of razor wire, with 15,000 troops on the streets of Washington, effectively placing the capital under military occupation, after Trump’s supporters stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

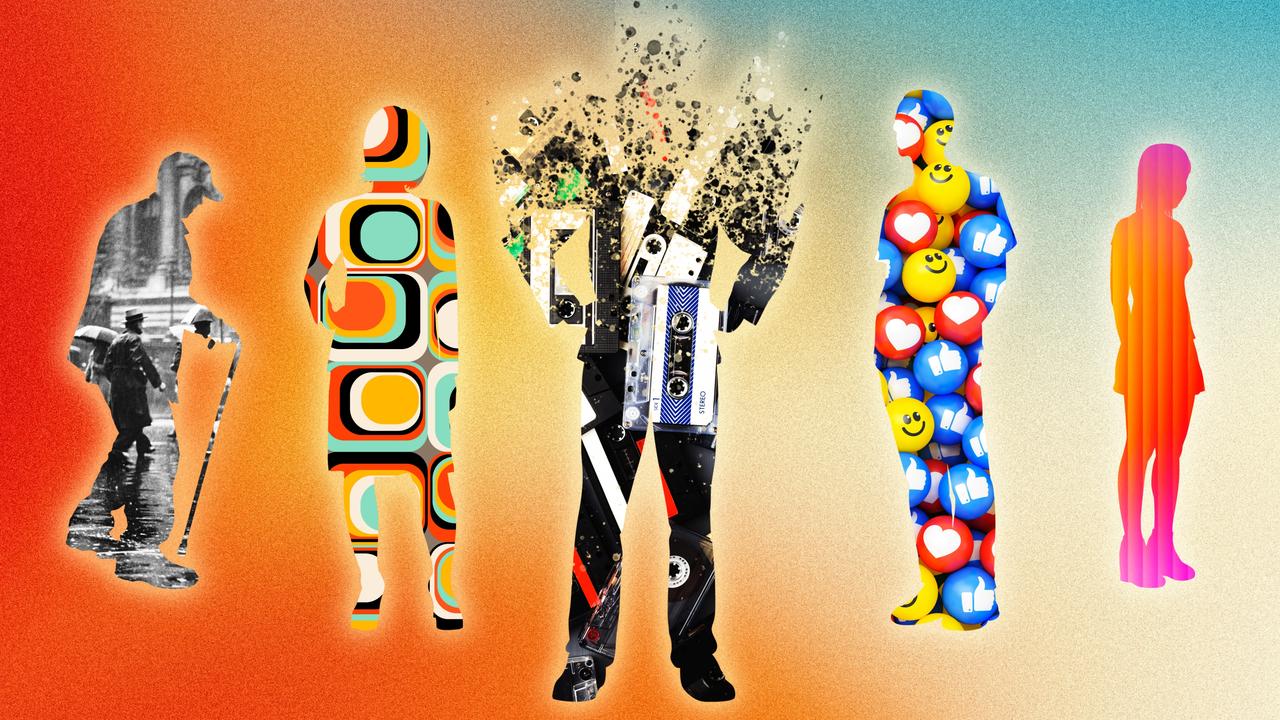

Thomas Matthew Crooks, the 20-year-old who allegedly shot Trump, would have been three months shy of his 12th birthday when Trump launched his campaign for president in June 2015. His entire adult life would therefore have been spent in a sharply polarised society, marinating in lethally intense rhetoric demonising Trump and Trump voters as racist and a threat to democracy on one side, and crudely vitriolic rhetoric from Trump and his supporters on the other.

Crooks might have seen Biden’s recent call to put Trump “in a bullseye”, heard him liken Trump’s rhetoric to that of the Nazis, seen last month’s New Republic magazine cover depicting Trump as Adolf Hitler or read Mike Godwin’s Washington Post article titled “Yes, it’s okay to compare Trump to Hitler. Don’t let me stop you.”

He might have heard celebrity role models – Robert De Niro, Kathy Griffin, Snoop Dogg, Madonna, Mickey Rourke – talking about how they would like to kill or seriously injure Trump. As a young teenager, Crooks might have heard Biden, then vice-president, say: “If we were in high school, I’d take (Trump) behind the gym and beat the hell out him.” Crooks might have seen Biden’s 2022 speech in nearby Philadelphia, where the President described Trump as representing “an extremism that threatens the very foundations of our republic”, an “assault on American democracy”, part of a “battle for the soul of this nation”.

A fortnight ago, Crooks might have read in the Huffington Post that the “Supreme Court Gives Joe Biden The Legal OK to Assassinate Donald Trump”.

This is not to justify Trump’s own inflammatory rhetoric during the same period, which could fill volumes. Neither is it to take sides on the substantive question of whether, indeed, the former president does represent a deadly threat to US democracy. It is merely to recognise that rhetoric has real-world consequences, and that the alleged shooter’s animus against Trump did not fall, fully formed, from a clear blue sky.

Likewise, none of this diminishes Crooks’ responsibility for his own actions. Neither, in itself, does it imply that Democratic politicians, celebrities and media personalities seriously sought to encourage someone to assassinate Trump.

But it does suggest that many of the same individuals’ current calls for calm and to “lower the temperature” are motivated more by fear of retaliatory violence from Trump’s supporters than by any deep change of heart.

It also invokes a certain cognitive dissonance: as journalist Stephen L. Miller wryly noted on X, “Every Democrat and media outlet tonight is like “Thank God Hitler is okay and wishing Hitler a speedy recovery.’ ”

Politicians worldwide run the risk, whenever they meet the public, that someone may do them harm. This is not restricted to a term of office – former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro survived a stabbing while campaigning in 2018, and former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was shot dead in 2022.

British parliamentarians Jo Cox (in 2016) and David Amess (in 2021) were both murdered while meeting their constituents. This year, South Korean Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung was stabbed and Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico shot, both surviving assassination attempts.

Interacting with ordinary voters is not optional but essential in a democracy. As a result, to engage safely with the public, political leaders rely on security teams that include personal bodyguards, an advance team scouting routes and locations for potential threats, and (at major events such as political rallies) a perimeter cordon and site security team.

In the US, the Secret Service is responsible for protecting the current head of state, former presidents, and other senior officials, but at events such as the Butler, Pennsylvania rally where Trump was shot, the service works with state and local law enforcement. Typically, the Secret Service is responsible for close-in protection, while concentric rings of security – typically, an inner cordon staffed by state police and an outer cordon controlled by local law enforcement – surround the main venue. Entry points are controlled and attendees must pass through airport-like scanners. Drones may observe rooftops around the venue, while counter-snipers are positioned on rooftops with high-powered optics to spot any threat.

Ideally, a single command post ties the security system together, with representatives from each agency sitting shoulder to shoulder in an operations centre, maps and video feeds creating a so-called common operating picture, and a unified radio communications network linking different security teams.

For major events, rehearsals and tabletop exercises are employed to wargame possible incidents ahead of time.

As details emerge, it seems that co-ordination in this case was lacking, at best, and that rules of engagement (perhaps also lack of a common communications net) may have slowed the response. Video from the event appears to suggest Secret Service snipers had Crooks in their sights before he fired but allowed him to shoot Trump before returning fire, indicating a potential hesitation over unclear rules of engagement. Local law enforcement allegedly also had personnel inside the building on to whose roof Crooks climbed, possibly using a ladder, to establish his shooting position.

Members of the public seem to have alerted police to Crooks’ presence well before he fired, but no move was made to get Trump off the stage, suggesting lack of unified communications, confusion as to whether Crooks belonged to one of the various security organisations, or both.

With different law enforcement teams blaming each other, Biden has called for an independent inquiry. Unsurprisingly – given current distrust and Biden’s previous rhetoric against Trump – Republicans plan to conduct their own investigation, rather than rely on the findings of a Department of Homeland Security whose secretary, Alejandro Mayorkas, the House of Representatives impeached in January over the illegal entry of at least eight million immigrants across the US border in the past four years. (Mayorkas was acquitted in April, along party lines, in the Democrat-controlled Senate.)

Mayorkas also has been the subject of complaints from independent candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr (whose father, then the Democratic presidential frontrunner, was assassinated in 1968) that the Department of Homeland Security denied repeated requests for protective security. Similar complaints have been made by Robert O’Brien, Trump’s former national security adviser, who claims he was denied protection by the department despite threats from Iran. In the wake of the Trump assassination attempt, Biden approved a security detail for Kennedy, but the Department of Homeland Security clearly is not seen as independent or impartial by Biden’s political opponents.

Thankfully, Australia has never lost a prime minister or federal MP to political assassination.

At least four state parliamentarians have been murdered, including Percy Brookfield (1921), Albert Whitford (1924), Hyman Goldstein (1928) and John Newman (1994), though in at least two of these cases the motive was personal rather than political. The Sydney Hilton Hotel bombing in 1978 was an attack on the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, not an assassination attempt against one political leader.

Further back, the shooting of Prince Alfred in 1868 by Henry O’Farrell was perhaps the closest Australia has come to a politically motivated assassination attempt on a public figure, albeit well before Federation.

Australia is far from immune to the threat of political assassination; arguably, no nation is. That said, we have four big advantages compared with the US.

The first is that Australian institutions – in particular, politically independent judiciary and non-partisan police – are far more trusted than in the US.

The Australian Federal Police, for example, has a reputation for impartiality. ASIO, from time to time, has been accused of heavy-handedness or a politicised approach to security intelligence – the 1973 raid on ASIO by attorney-general Lionel Murphy is a case in point – but no breakdown of trust has recurred in more than half a century. Governments of all political persuasions have trusted police and intelligence services to carry out the direction of elected leaders, accountable through parliament to the Australian people.

Of course there has been controversy over effectiveness, or the appropriateness of authorities such as ASIO’s recently debated questioning and detention warrant powers. But, crucially, neither the AFP nor ASIO is widely seen as being in the pocket of one particular political party, or targeting that party’s domestic political opponents.

In contrast, before the US mid-term election in 2022, only 50 per cent of American adults surveyed trusted the FBI “to do what is right” all or most of the time, with 50 per cent trusting the bureau only “some of the time” or “hardly ever”. The same survey showed a partisan divide, with Democrats expressing dramatically higher trust than Republicans, and younger people across both parties expressing lower trust than older voters.

In January this year, 25 per cent of American adults in a separate poll said they believed FBI operatives probably or definitely organised and encouraged the 2021 Capitol attack. This suggests that, however sincere political leaders may be in walking back previous inflammatory rhetoric, large segments of the US population now lack confidence in the impartiality of law enforcement.

This is dangerous ahead of yet another fraught election. Several Republican politicians have called for the breaking up of the FBI (which performs law enforcement and domestic intelligence functions), so a Trump victory this November arguably threatens the institutional survival of the FBI.

Any perceived partisan slant to the bureau’s behaviour – as in 2020, when the FBI sat on the knowledge that Hunter Biden’s “laptop from hell” was genuine, even as 51 former intelligence officials falsely claimed it was Russian misinformation – could undermine stability at a crucial moment.

A second advantage for Australia is that our borders are secure. This is not a question of illegal entry or undocumented migration, though this is a source of controversy that has raised the political temperature in the US, Europe and elsewhere. Rather, in an environment of great-power conflict, hybrid warfare and targeted assassination of political leaders by nation-states, a large uncontrolled influx creates cover for infiltration by external actors seeking to destabilise a society.

Between October 2022 and February last year, US Customs and Border Protection encountered more than 4200 Chinese migrants illegally crossing the southern border, including “hundreds of military-aged males”.

Earlier this year, FBI director Christopher Wray briefed congress on a surge in border crossing by known or suspected terrorists over the past five years, and Customs and Border Protection intercepted an alleged Hezbollah bombmaker crossing the border. Such an influx not only makes it easier for hostile foreign actors to enter a country but also brings suspicion on all foreigners (or anyone perceived as foreign), increasing internal tension.

Third, most obviously, Australia has far lower levels of gun ownership than the US. As several recent stabbings have shown, even in the absence of firearms a determined or deranged attacker still can inflict significant death and destruction. But the widespread availability of long-range, rapid-fire weapons in the US enables a degree of damage that dwarfs anything seen in Australia since the 1990s.

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent nationwide rioting and unrest of 2020, numerous armed militias stood up in the US, often linked to local communities. There was also a substantial increase in gun purchases, primarily from left-leaning or liberal population groups – an unprecedented surge in first-time gun buyers, particularly African-Americans and women, that continued through 2021. (Right-leaning and conservative populations were as well-armed as their left-leaning counterparts but were already thoroughly armed before the pandemic.)

Even since the 2020 surge subsided, gun purchases continued apace: in the first quarter of this year, the most recent for which data is available, Americans purchased 5.48 million guns, roughly 1.3 million a month. Obviously, in a society as heavily armed as the US, prevalence of firearms makes protecting politicians much more difficult.

Finally, though it may not always seem so, Australia has much less inflammatory political rhetoric, a far greater degree of national consensus and greater shared commitment to peaceful political dialogue than the US. This is not something to be taken for granted – erosion of peaceful norms happens slowly and imperceptibly at first, but once it takes hold it can be extraordinarily difficult to reverse, as this week’s events have shown.

Australians of all persuasions owe it to ourselves to prevent that erosion from happening.

David Kilcullen served in the Australian Army from 1985 to 2007 and was a senior counterinsurgency adviser to General David Petraeus in 2007 and 2008.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout