Folbigg’s question of innocence or guilt will be in the genes

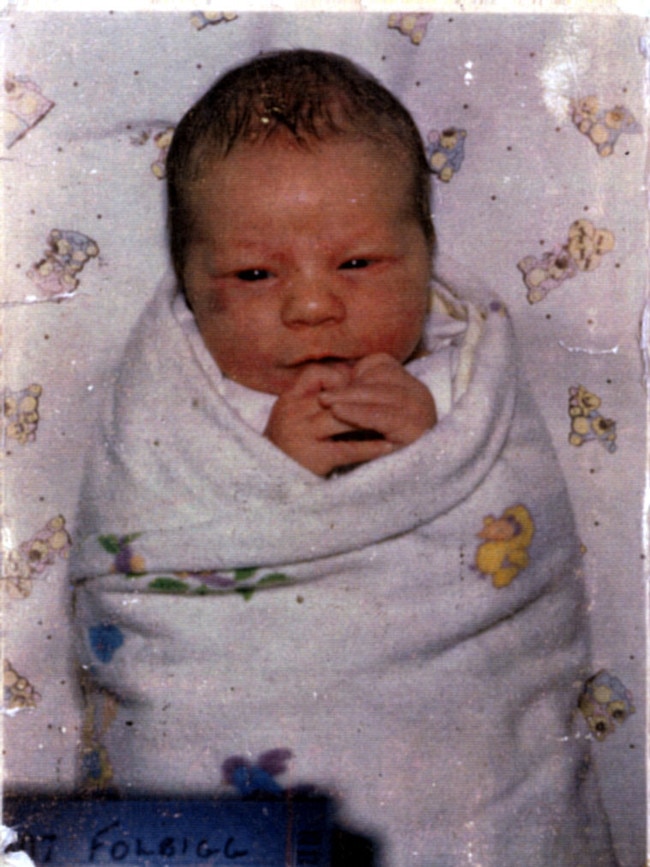

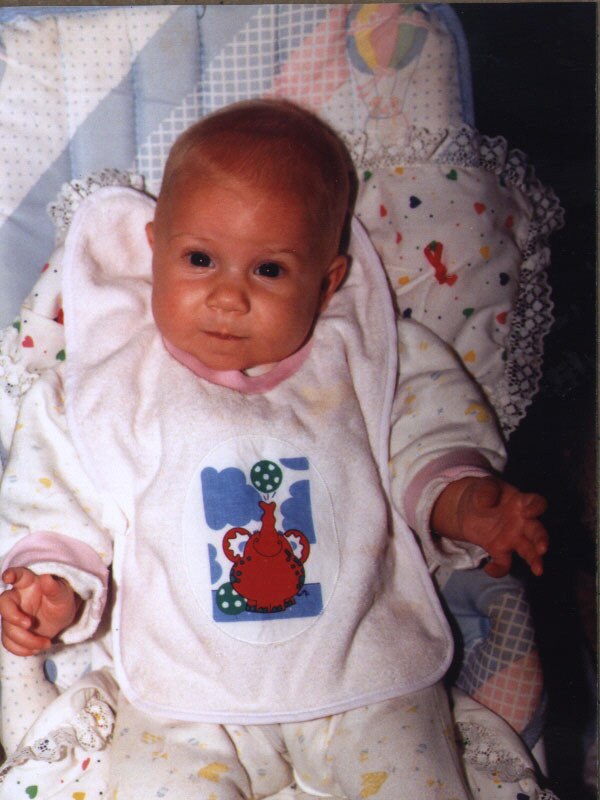

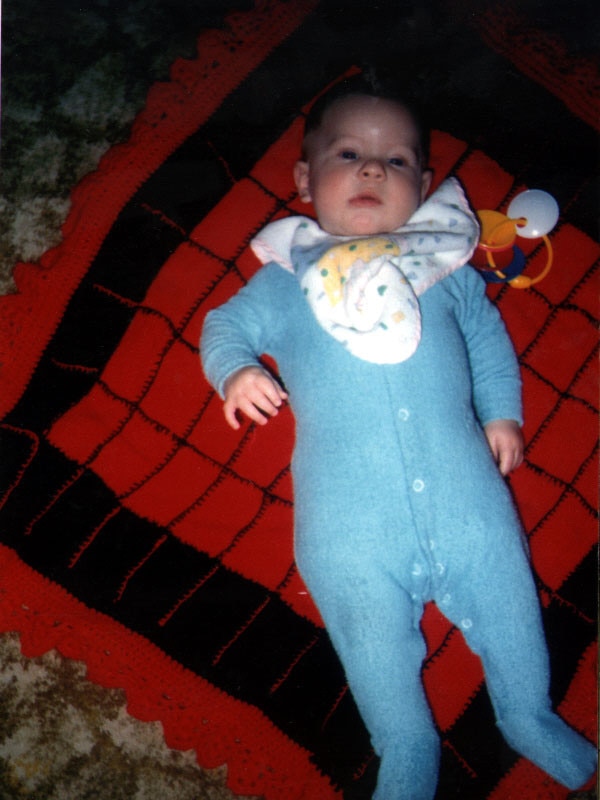

Did the genetic variant carried by convicted child killer Kathleen Folbigg — and which, scientists say, she passed on to two of her children — trigger their deaths?

“It all comes down to this!” is a well-worn refrain all too familiar to fans of MasterChef and reality television.

On Monday, in a far more sober setting, the guilt or innocence of Kathleen Folbigg, a mother convicted of killing all four of her children, will come down to this: did the genetic variant she carries and which, scientists say, she passed on to two of her children trigger their deaths?

That judgment will be made by a former chief justice of NSW, Tom Bathurst AC KC, as he presides over a fresh inquiry into her convictions that could see her walk free after 19 years in prison.

In 2003, Folbigg was convicted of the murder of three of her children, Patrick, Sarah and Laura, and the manslaughter of her firstborn, Caleb. Two subsequent unsuccessful appeals and a judicial inquiry in 2019 failed to clear her name.

She has been in prison ever since and continues to protest her innocence.

The trial took place at a uniquely ill-fated time for Folbigg. The police investigation was triggered by Laura’s untimely death in 1999, and their suspicions were buttressed by the views of a British pediatrician, Sir Roy Meadow, that in a single family, “one death is tragic, two is suspicious, and three is homicide unless proved otherwise”.

By the time she came to trial four years later, this theory had been debunked and any reference to it was ruled inadmissable.

But that didn’t prevent the prosecutor, Mark Tedeschi, from articulating Meadow’s Law – as it came to be known – in a roundabout way.

Rather than quote it directly, he compared the births of Folbigg’s four children to piglets being born to a sow – with wings attached. Could all four deaths be from natural causes, he asked rhetorically. Yes, they could but, equally, pigs might fly, he inferred in his closing address. It was, he suggested, fantasy to think otherwise.

But Tedeschi’s assertion that there had never been a reported case of three infants in a family dying from natural causes was wrong. Other confirmed cases of multiple infant deaths from natural causes in a single family were recorded before 2003.

Meanwhile, as the science of genetics has advanced exponentially in the two decades since 2003, so, too, has the realisation that unique events do occur for genetic reasons.

In 2019, a previous inquiry into Folbigg’s convictions ended with the commissioner, former NSW District Court chief judge Reginald Blanch, declaring that the evidence he had heard “reinforces Ms Folbigg’s guilt”.

Genetic sequencing formed part of the evidence presented to that inquiry, confirming that Folbigg and her daughters, Sarah and Laura, were born with a cardiac mutation, CALM2 G114R, which scientists say can cause lethal cardiac arrhythmias and which later experiments would show “likely precipitated the natural deaths” of Folbigg’s two daughters.

The scientists concluded that Folbigg was a mildly symptomatic carrier and that fatal arrhythmic events were triggered in both Sarah and Laura as a result of “intercurrent” infections at the time they died.

Sarah had a respiratory infection and had been given antibiotics, while an autopsy found Laura to be suffering from myocarditis – an inflammation of the heart muscle that can be fatal.

Caleb had respiratory difficulties from birth attributed to laryngomalacia (a floppy larynx) and died at 19 days of age, while Patrick develop a severe seizure disorder and blindness from four months of age, and died during an epileptic fit four months later.

Carola Vinuesa and Todor Arsov, from the Australian National University, who together found the novel variant in the CALM2 gene, will be key witnesses to these genetic findings, as will Michael Toft Overgaard and Mette Nyegaard, from Aalborg University in Denmark, who have continued to conduct experiments demonstrating that the mutation is damaging and likely capable of triggering fatal arrhythmias in young children while they sleep.

Last year John Shine, a former president of the Australian Academy of Science, said: “We have very strong, robust scientific evidence that the mutations in these children could certainly have played a major role in their susceptibility to sudden death.”

Describing Folbigg as “a victim of the genetic lottery”, he added: “She’s extremely unlucky because the chance of having the particular mutation she’s got is very, very low. It’s almost non-existent in the rest of the population.

“However, once you have that mutation in the family, then your genetic blueprint has that mutation. And so the chance of passing that to your children and their children is incredibly high.”

This assertion, from one of the world’s foremost genetic experts, lies at the heart of next week’s hearing. But, even with the new science in this case, it won’t be a walkover for Folbigg or an automatic affirmation of the petition lodged with the Governor of NSW last year and endorsed by more than 150 scientists and science advocates – among them, three Nobel laureates – calling for her pardon and release.

Contesting the hypothesis that the genetic mutation triggered the deaths of her daughters will be one of the scientists who was sceptical of the theory at the last inquiry in 2019. Pediatric cardiologist Jonathan Skinner, from the University of Auckland, told that inquiry there was no convincing evidence for the presence of any known form of cardiac inherited disease as a potential cause for the sudden death of the four children.

This, though, made no acknowledgment that mutations in the calmodulin genes have killed children in similar circumstances, with these deaths recorded in an international registry curated by a world-leading expert in the genetics of cardiac arrhythmias, Peter Schwartz. Schwartz will be another key witness at this inquiry.

Two separate hearings will form the basis of this inquiry: the first, starting on Monday, will launch into the genetic evidence. The second hearing, next February, will continue examining the genetic evidence, and also will hear from psychiatrists and psychologists who will give their opinions on the diaries that, at her trial, helped to convict Folbigg.

It’s an exercise that her supporters confidently predict will bury, once and for all, the notion that the diaries contain “virtual” admissions of guilt to having killed her children.

In the end, it all comes down to this: will the genetic and psychiatric evidence raise “reasonable doubt” about Folbigg’s convictions?

Even if it does, there still may be a long, hard road ahead for her. The eventual outcome may be a pardon, which of itself will not ensure that her convictions are quashed.

There is, some argue, another factor in play here – the crude political consideration of setting free a mother once labelled “the most hated woman in Australia”.

Mark Speakman, the NSW Attorney-General, has praised the “stoicism” of Folbigg’s former husband, Craig, who has consistently declined to provide a DNA sample that would help the scientists establish whether the couple’s two boys also might have carried a pathogenic genetic variant.

And while acknowledging the need to hold a fresh inquiry, he commented: “I can well understand why members of the public may shake their heads and roll their eyes in disbelief about the number of chances Ms Folbigg has had to clear her name, and why does the justice system allow someone who has been convicted of multiple homicides yet another go.”

The signs are the Liberal NSW government is unlikely to free Folbigg if it can help it ahead of next year’s state election in March – and potentially the ultimate responsibility for deciding Folbigg’s fate may then fall to a Labor attorney-general. How sad if, in the end, it all comes down to politics.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout