The law says Kathleen Folbigg killed her four babies. Scientists say there’s reasonable doubt

With scientists weighing in on the vexed case of convicted child killer Kathleen Folbigg, will she finally be released?

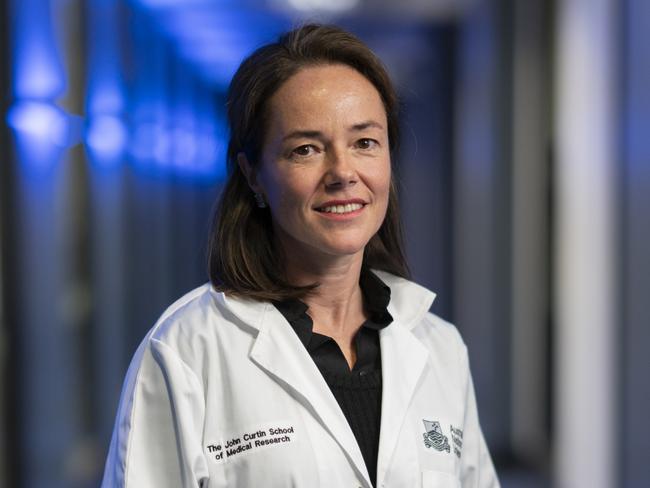

In the international scale of brainpower, Carola Vinuesa is a star. “You don’t get to be a fellow of the Royal Society if you are not a high‑achieving person,” says the nation’s former chief scientist Ian Chubb. “She’s a truly credible, smart scientist. I would rate her very highly. I would say that her peers rate her very highly.”

An expert in discovering genetic disease, and based until recently in Canberra, Vinuesa has spent years as an immunogeneticist, her achievements internationally recognised. Yet on the July morning before she is inducted into one of the world’s most auspicious scientific bodies, joining Charles Darwin, Albert Einstein and more than 80 Nobel laureates with a Royal Society fellowship, she feels the need to justify her credentials. “I have been doing this for a long time,” she says of her distinguished career. “We have serious science here.” That the subject behind that specific science is a mother convicted in 2003 of killing her four children has compounded Vinuesa’s attempts to have it taken seriously.

In the national discourse Kathleen Folbigg, dubbed the nation’s worst female serial killer, is a stoic woman with comparatively few admirers. “I think the public says, ‘Well, the courts have found her guilty, she should serve her time’,” says Anna-Maria Arabia, chief executive of the Australian Academy of Science and one of a growing scientific cohort concerned about the conviction of the now 55-year-old mother serving 30 years’ jail with a 25-year non-parole period. “It appears to be the grossest miscarriage of justice that we have ever seen in Australia since Lindy Chamberlain. It would make the Lindy Chamberlain case pale into insignificance.”

The scientific whispers behind that view have risen to a roar, and now an unprecedented number of Australian scientists is calling for the exoneration of the convicted multiple murderer, adamant that the case against Folbigg is circumstantial and that at least two of her children died from a rare genetic mutation. By stepping out of laboratories and into the world of justice, they assumed that their professional opinions, in many cases based on decades of experience, would be readily accepted. Instead they have encountered a lengthy stand-off of expertise: fact versus interpretation, black and white versus nuance, science versus the law.

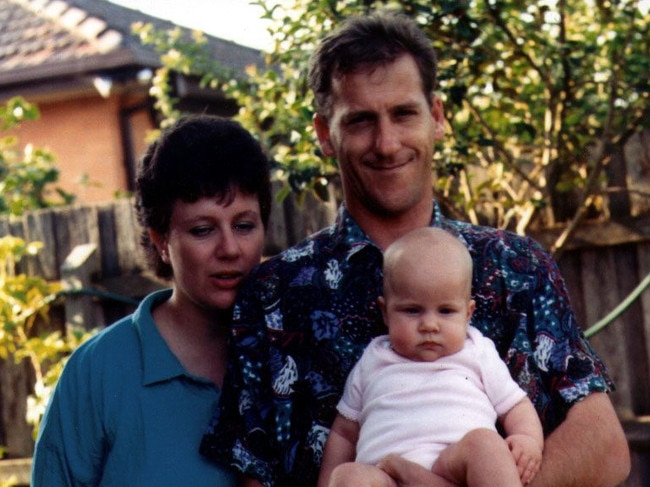

Over the course of one agonising decade, all of Craig and Kathleen Folbigg’s children died. Caleb lived for 19 days, Patrick for eight and a half months and Sarah for two months longer. Only Laura made it to her first birthday before her mother discovered her, too, unresponsive. “My baby’s not breathing,” Folbigg told an emergency operator in March 1999. “I’ve had three go already.” At 18 months and 22 days, her fourth child also died.

On any level, four babies dying is more than a lifetime’s quota of heartbreak. It is also one of the key points of agreement amid a divergence of expert opinions on the loss of Craig and Kathleen Folbigg’s family. As a devastating series of coincidences, the fatalities seem inexplicable. But they also share similarities. All the children died suddenly, at home, in their sleep, with no signs of injury, and each was found by their mother, who had endured her own childhood misfortunes. As a toddler, Kathleen Folbigg was made a ward of the state after her father murdered her mother, and she had an isolated childhood with few friends. At 18 she met Craig Folbigg, a forklift driver, at a disco. They married two years later, rented a flat in Newcastle, north of Sydney, and started a family.

But their joy at new parenthood lasted only days and precipitated an endless chain of anguish. Caleb’s death in early 1989 was ascribed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Almost two years later, Patrick, who had seemed healthy until seizures left him with brain damage at four months, was found to have died from asphyxia following an epileptic fit. The August 1993 death of Sarah, who at four and a half months had been thriving and developmentally normal, was also listed as SIDS.

By the time forensic pathologist Dr Allan Cala began an autopsy on Laura in March 1999, he was aware of the family’s triple tragedies. By then, Folbigg had packed away every photo of her children. “The death of Laura Folbigg cannot be regarded as ‘another SIDS’,” Cala wrote in his final report late that year, in which he listed Laura’s cause of death as undetermined. “The family history of no living children following four live births is highly unusual.” Although there were signs of heart inflammation, “this may represent an incidental finding. The possibility of multiple homicides in this family has not been excluded. If homicidal acts have been committed it is most likely these acts have been in the form of deliberate smothering.”

“It appears to be the grossest miscarriage of justice that we have ever seen in Australia since Lindy Chamberlain. It would make the Lindy Chamberlain case pale into insignificance”

By then police were already investigating. In April 2001, her increasingly rocky marriage over, Folbigg was charged with four counts of murder.

“There has never, ever been in the history of medicine any case like this,” crown prosecutor Mark Tedeschi QC told the jury at the NSW Supreme Court in Sydney two years later, noting the unlikelihood of four babies in one family dying of SIDS or minor illnesses, all being found soon after their death and by their mother. “It’s probably more common that a person has been hit by lightning than what has happened in this family.”

Accused of smothering her children, Folbigg insisted she was innocent. But due in significant part to incriminating passages from her diary – including “with Sarah all I wanted was her to shut up. And one day she did”; “obviously I’m my father’s daughter”; and “She’s [Laura] a fairly good-natured baby. Thank goodness. It has saved her from the fate of her siblings. I think she was warned” – in May 2003 a jury found her guilty of three counts of murder and one count of manslaughter, of Caleb.

“The evidence showed that natural but unexplained death was rare in the community and that there was no demonstrated genetic link to explain multiple deaths in a single family,” Justice Graham Barr found. He added: “The offender was not by inclination a cruel mother. She did not systematically abuse her children. She generally looked after them well, fed and clothed them and had them appropriately attended to by medical practitioners.” But her prospects of rehabilitation were negligible. “She is remorseful but unlikely ever to acknowledge her offences to anyone other than herself. If she does she may very well commit suicide. Such an end will always be a risk in any event.”

Folbigg was sentenced to 40 years in jail – one of the longest terms set for a female in NSW. Though the term was later reduced to 30 years, she kept trying to prove her innocence. But after almost 20 years of imprisonment, multiple unsuccessful appeals, several applications to the High Court, an inquiry, and a judicial review of that inquiry, Folbigg appeared to have exhausted all options. Not due for release before 2028, her fate seemed set. And then science intervened.

Could four children in one family just die? The terrifying possibility shadowed the case from the outset. The prosecution relied heavily on a now debunked concept known as Meadow’s Law, named after British paediatrician Roy Meadow, who fostered the notion that one sudden infant death was a tragedy, two were suspicious and three were murder, until proven otherwise.

In her 2011 book Murder, Medicine and Motherhood, Australian-educated academic Emma Cunliffe, whose PhD had focused on wrongful convictions for unexplained infant deaths, maintained that Folbigg “was tried at a moment in which there was a particularly strong emphasis on homicide as the most likely explanation of recurrent unexplained infant death within a family”. It was also a moment in which those unexplained deaths were disproportionately blamed on mothers.

The book had a profound effect on a highly respected forensic expert in Melbourne. Professor Stephen Cordner, then head of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, reviewed Cunliffe’s book for the Journal of Forensic Sciences and was impressed by its rigour. Over the following year, a lot of it in his spare time sitting at his kitchen table, Cordner probed the Folbigg case. Compiling a 100-page report – the longest in his long career – he concluded that all the children appeared to have died of natural causes: Caleb and Sarah likely due to SIDS, Patrick from an unexplained life-threatening event, and Laura from myocarditis, inflammation of her heart.

Referring to a “homicide hypothesis which in fact has little forensic pathology content”, he acknowledged that an infant could be smothered without leaving any evidence. But he added: “In my view, much of the forensic pathology discussed at the trial is misconceived, based as it is on a flawed understanding of asphyxia… Ultimately, and simply, there is no forensic pathology support for the contention that any or all of these children have been killed, let alone smothered.”

As for the supposed impossibility of four siblings dying of natural causes, he noted that “two or three unexplained deaths in the one family probably occur more frequently than the same number of hidden homicides.” He added: “The very existence of the enigma of SIDS demonstrates how little we know about why some babies die… If the convictions in this case are to stand, I want to clearly state there is no pathological or medical basis for concluding homicide. The findings are perfectly compatible with natural causes.” In 2015, Folbigg’s lawyers included Cordner’s report in a petition for an inquiry into her conviction. Three more years passed before NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman announced a review headed by former District Court judge Reg Blanch.

Around the time of the 2018 announcement, Carola Vinuesa was at work at the Australian National University in Canberra when she was contacted by a former student, now a lawyer, who had completed his honours in immunology and wondered about the merits of seeking a genetic cause for the babies’ deaths. Vinuesa had not heard of the Folbigg case, but agreed it was worth probing given that medical advances were identifying so many more genetic causes of rare diseases. Nor was she as surprised as others at the multiple fatalities, which are not unheard of in her field; just a month earlier she had been referred the case of a Macedonian family in which four children, aged between 20 days and four months, had died, and a genetic cause had been found.

In October 2018, Vinuesa and some colleagues began searching for possible genetic causes for the deaths of the four children. They soon found that Folbigg had a mutation in the CALM2 gene that had never been seen previously. As a new discovery, this specific mutation was not yet documented. But other mutations in this gene had been linked to heart problems and were known to cause sudden death in children. As some of the country’s leading scientists would later attest in a widely publicised petition, mutations in this gene group “are one of the best recognised causes of sudden death in infancy and childhood, both while asleep and awake”.

Vinuesa sent her findings to Folbigg’s lawyers and late in 2018 she was invited to join one of two expert teams at the just announced Blanch review, investigating genetics and advancements in DNA since the trial. Soon after, Sarah and Laura were found to have the same CALM2 gene mutation as their mother. (The mutation was not found in the boys, who had originally been deemed to have died of natural causes, Caleb to SIDS and a floppy larynx, and Patrick as a result of severe epilepsy.)

Despite her acclaim, Vinuesa’s proficiency did not extend to little-known mutations of the CALM2 gene. So she began to scour the globe for expertise, and in mid-2019 she contacted Italy- based Professor Peter Schwartz, a world leader on life-threatening heart problems resulting from CALM mutations. He was also curator of an international registry, compiled to understand more about CALM mutations and containing details of 74 people (now 134) with irregularities in that gene. From it Schwartz learnt of a family whose genetic mutation and circumstances appeared almost the same as Folbigg’s: two young children of a seemingly healthy mother had cardiac arrests, one of them fatal. As Schwartz soon replied to Vinuesa about Folbigg’s case: “My conclusion is that the accusation of infanticide might have been premature and not correct.”

Schwartz’s findings were relayed to inquiry head Reg Blanch but by then the hearings had ended, and evidence and submissions were closed. Given the significant advances in genetics since Folbigg’s trial nearly 20 years earlier, during the inquiry two teams of experts had probed genetic variants, as the final report would reveal. Although they did not have a sample of Craig Folbigg’s DNA, a Sydney team believed that the available evidence did not meet the threshold to say that the CALM2 genetic mutation caused disease that could kill, and certainly not in such young children. It was also hard to reconcile two babies’ deaths with a variant that was also present in their healthy mother. (The dissenting experts contacted for this story either did not respond or declined to be interviewed.) Vinuesa’s Canberra team, on the other hand, considered that the variant found in Folbigg and her daughters was likely pathogenic and therefore capable of causing disease.

“In my view, much of the forensic pathology discussed at the trial is misconceived, based as it is on a flawed understanding of asphyxia… Ultimately, and simply, there is no forensic pathology support for the contention that any or all of these children have been killed, let alone smothered”

“Professor Vinuesa is a very experienced and eminent researcher and is, I guess, approaching this in the way that you might approach a research project, thinking about possibilities, expanding the different areas of knowledge that we currently have,” genetic pathologist Professor Edwin Kirk, a member of the Sydney team, was quoted in the inquiry’s final report, describing the differences between the two groups. “Whereas our approach is more focused on known disease associations.”

When that report was released in July 2019, Blanch found there was no reasonable doubt about Folbigg’s conviction, based largely on interpretation of her diaries and the rarity of multiple SIDS cases in one family. While the new information from Schwartz meant it was now plausible that the girls might have had a cardiac condition “that raises a possibility it caused their deaths”, he found that “there is no reported case of a death of such nature – asymptomatic sudden cardiac death in infancy during a sleep period – being associated with a calmodulin variant. If so associated, Sarah and Laura’s deaths would be the first and second reported cases of their kind.”

On their differences about the genetic variants Blanch chose to “prefer the expertise and evidence of the Sydney team”, adding that “on the evidence before the inquiry I find that there is no reasonable possibility that any of the Folbigg children had a known or recognised pathogenic or likely pathogenic genetic variant which caused their deaths”. The only conclusion reasonably open “is that somebody intentionally caused harm to the children, and smothering was the obvious method”. He concluded: “The evidence at the inquiry does not cause me to have any reasonable doubt as to the guilt of Kathleen Megan Folbigg for the offences of which she was convicted. Indeed, as indicated, the evidence which has emerged at the inquiry, particularly her own explanations and behaviour in respect of her diaries, makes her guilt of these offences even more certain.” There had been, it seemed, no miscarriage of justice. Again Folbigg appealed. In March last year, the NSW Court of Appeal deemed that the inquiry’s conclusion was not at odds with scientific evidence.

The Australian Academy of Science is the nation’s oldest learning academy and a leading authority on scientific endeavours, its members more accustomed to the intricacies of clinics than court rooms. “Carola, as a highly respected fellow of the academy, after that inquiry she came to myself and the academy and basically said, ‘What can we do about this? We haven’t been able to present these scientific facts’,” says molecular biology professor John Shine, the pioneer of gene cloning who recently finished his term as president of the Australian Academy of Science. “What else could we do but petition for her [Folbigg’s] release based on that evidence? Because this is the right thing to do.”

By then 27 world-leading scientists, including Vinuesa and Schwartz, had published a peer-reviewed study in an Oxford University Press medical journal, EP Europace, concluding that the Folbigg girls likely died from a lethal cardiac mutation that disrupted their heartbeats. (The study found a different genetic mutation in the boys that was known to cause lethal epilepsy in mice.)

On the back of that report, last year nearly 100 scientists, including Shine and Australian Nobel Laureates immunologist Peter Doherty and molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn, signed a second petition and called for Folbigg to be pardoned: Blanch’s conclusion, they said, “runs counter to the scientific and medical evidence that now exists. This is because a natural cause of death for each of the children has been ascribed by qualified experts.”

As the petition was passed to some of the country’s most eminent scientific minds, Shine was amazed at their enthusiasm. “They really wanted to be involved. They wanted to sign it. And that’s a very diverse group of people. I don’t think I have ever seen them agree on anything before. They were very independent minds. But once they saw the data and the science, they knew it was right.” It was not the first time science had stepped into the world of justice; after the second inquest into the death of Azaria Chamberlain, leading immunologists signed a petition questioning supposed blood samples found on items belonging to the baby’s later exonerated parents. But this was the widest and possibly the loudest intervention.

“The evidence seemed to be very strong and convincing,” says former chief scientist Ian Chubb, who had never previously signed a petition calling for the overturning of a murder conviction in his decades-long career. “I thought there was enough room for doubt and that there should be another inquiry.”

The 14-page document declared that the case against Folbigg was “entirely circumstantial”, based on flawed logic that the likelihood of four children dying in one family of natural causes was virtually impossible. “…a reasonable person should have doubt about Ms Folbigg killing her four children. Deciding otherwise rejects medical science and the law that sets the standard of proof,” the petition stated, adding: “Ms Folbigg’s case also establishes a dangerous precedent as it means that cogent medical and scientific evidence can simply be ignored in preference to subjective interpretations of circumstantial evidence.”

Not everyone, however, was convinced. As the number of names on the petition increased, some in the Australian scientific fraternity were concerned by the strength of the voice and conviction being afforded the petition when many of the signatories were not cardiac or diagnostic experts. As one dissenter says: “Many of the scientists have no business getting into this… It would be like you or I finding a document that made complex comments on structural engineering. Most of the people have no competence to make comments on this issue.”

The deaths of the Folbigg children have been are current issue for NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman, who in May this year decided against recommending a pardon for Folbigg, opting instead for a second inquiry. “Notwithstanding that Ms Folbigg has already had numerous attempts to clear her name, this new evidence, and its widespread endorsement by scientists, cannot be ignored.” The second inquiry, headed by retired NSW Supreme Court chief justice Tom Bathurst QC, begins in November.

Regardless of its outcome, some senior scientists are pushing for changes to the way in which their expertise is considered by courts henceforth. Shine doesn’t feel that scientific knowledge has been properly taken into account in this case in particular. “One of the big problems I believe in the system is that whilst the court does hear views from different science experts at the time, they are usually experts appointed by the defence and the prosecution to in a sense bolster their end case.” He believes it would be much more effective for courts to appoint their own independent scientists. “In this case there was an eminent scientist who happened to have been involved by chance, whereas that won’t always happen.”

At the moment in Australia there is no dedicated body to consider new scientific evidence after the appeals process ends; much of the scientific help that Folbigg has attracted has occurred by happenstance, with scientists or doctors beavering away voluntarily in their spare time or offering to help. A possible solution is a criminal case review commission, similar to those established in Norway, the UK, Canada and New Zealand, so that decisions are not left to an elected official but made by an independent body that can in turn suggest independent experts. “The way science is changing, it can get ahead of the law,” says Chubb. “But it doesn’t mean it should be ignored.”

As for those who are adamant that the science, in this case, overwhelmingly favours a grieving mother rather than a mass killer, might they in fact be trying to find medical answers to explain away multiple murders? In an enduring case riddled with controversy, one medical expert thinks this may be the most ridiculous theory of all. “Why would you waste your time?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout