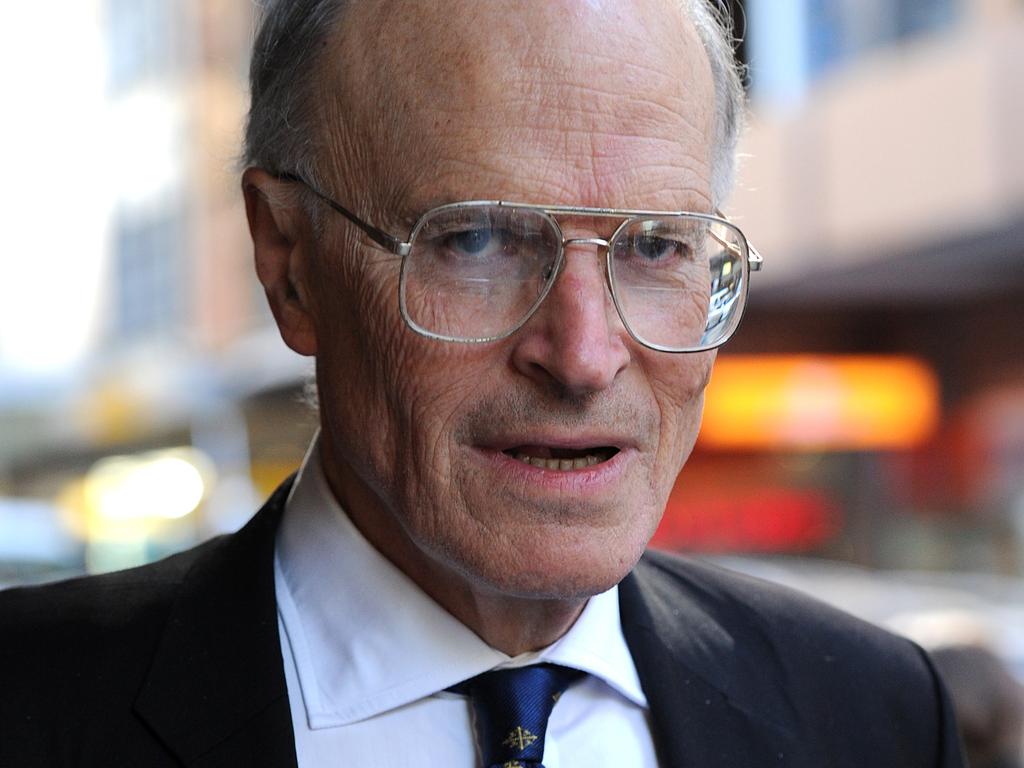

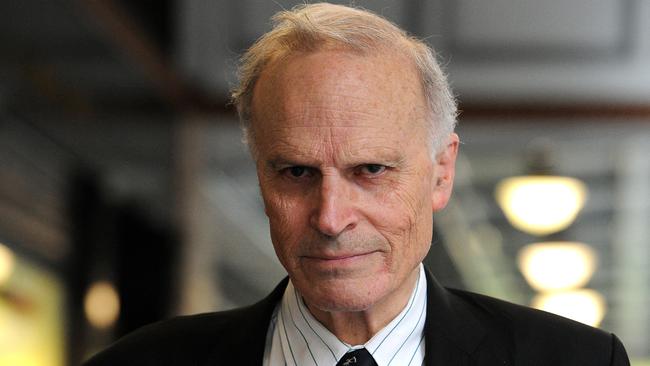

Dyson Heydon and the legal professions’ ‘dirtiest secret’

In courts, barristers’ chambers and law firms across the country, there are men now quaking in their boots.

In courts, barristers’ chambers and law firms there were men quaking in their boots this week.

Or, at least, female lawyers were hoping they might be.

The lid was lifted on what was described as the profession’s “dirtiest secret”.

A giant of the law — former High Court judge Dyson Heydon — had his reputation shredded, his name erased from Eight Selborne chambers where he worked.

Heydon “categorically” denies wrongdoing. However, an independent High Court investigation found he sexually harassed six associates, five who worked for him, during his decade on its bench.

The shameful toll of harassment was laid bare.

At least three of the women, among the best and brightest of their law school cohort, have left the profession after the most promising start possible to their careers — a High Court associateship.

None of it shocked those female lawyers this week.

They have watched for years as male rainmakers kept their jobs and unsavoury allegations were swept under the carpet — a small payout and a non-disclosure agreement often used to silence victims while serial offenders rose up the profession’s ranks.

Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins has been on a crusade to prevent the damaging use of blanket NDAs since she finished an inquiry into workplace sexual harassment that arose out of the #MeToo movement.

While she points out there is a place for confidentiality — women might be just as keen as men to protect their privacy — they also can be used to enforce a culture of silence.

“It can conceal the unlawful conduct, facilitate repeat offending, and the other thing that concerned me was there were no systemic lessons learnt,” she says.

Only two major law firms — Clayton Utz and Herbert Smith Freehills — were willing even to provide a limited waiver to their NDAs to allow victims to make a confidential submission to the Australian Human Rights Commission’s harassment inquiry.

Jenkins says NDAs should be drafted in more sophisticated ways, so they allow for the exposure of serial predators and provide exceptions; for example, for women to go to police or discuss traumatic events with their families.

Jenkins’s final report in March revealed sexual harassment was pervasive in every profession.

It is clear #MeToo has yet to achieve wholesale change in any sector.

But the legal profession has particular vulnerabilities, with its hierarchical structure and close working relationships.

At the pinnacle there are the judges, many with healthy egos and tenure until retirement.

They can seem almost untouchable, and mostly they are — just one judge has been removed from office in more than 30 years. There have been a stack of reports across many years exposing rampant harassment in the legal profession.

The most recent, from the Victorian Legal Services Commissioner in April, showed one in three respondents had experienced sexual harassment — the majority in the past five years and 25 per cent in the previous 12 months.

Law Council of Australia president Pauline Wright says lawyers depend on personal connections, both to win work and to advance up the chain.

“Baked into that process is a power dynamic where the more senior practitioners necessarily have power over the career progression of the less senior practitioners,” she says.

Even when women are brave enough to speak out, complaints can go nowhere.

As The Australian revealed this week, a NSW Supreme Court judge was told Heydon had made unwanted advances towards one of its young female employees two years ago but did not take any action.

Dhanya Mani, 26, was working as a tipstaff to NSW Supreme Court judge Guy Parker in 2018 when she told him about alleged harassment by Heydon.

Parker informed NSW Chief Justice Tom Bathurst only this week of Mani’s allegations.

The court says Mani did not ask Parker to take the matter any further, but she told The Australian that she had hoped when she raised the matter he would do something about it.

Bathurst has now asked the state’s judicial commission to prepare an education program for judges on what to do if an allegation is made. The court says judges were not previously trained on the issue because it was generally expected they would have been educated in their previous careers.

The High Court has refused to say when concerns about Heydon’s behaviour were first raised with its judges. However, the investigation by former inspector-general of intelligence and security Vivienne Thom noted that former High Court judge Michael McHugh was told about one of the alleged incidents by his then associate, Sharona Coutts. Coutts told the investigator that McHugh told her he had spoken to then chief justice Murray Gleeson.

That was back in 2005.

Another of Heydon’s former associates, Chelsea Tabart, allegedly went on to be harassed in 2012. She told The Sydney Morning Herald she left the law because the culture was broken from the top down and she did not feel she would be safe “from powerful men like Mr Heydon” even if she reported them.

Heydon remained on the court until his retirement in 2013.

He is also alleged to have groped former ACT Law Society president Noor Blumer at a university dinner.

The heads of the federal courts and tribunals issued a rare joint statement on Friday condemning sexual harassment as “unlawful and wholly unacceptable”.

The five chiefs — all men — said they were taking steps to review their policies and procedures to ensure they were effective and that all staff had the confidence to raise concerns or complaints.

High Court Chief Justice Susan Kiefel also has vowed to make changes that would prevent such misconduct in future. This includes a new HR policy and the appointment of a supervisor who could provide support to associates if needed.

Her strong statement this week — that she and her fellow judges were “ashamed” such behaviour could occur at the High Court and that the women’s accounts of their experiences had been believed — sent the message loud and clear to the profession that this sort of conduct would no longer stay under the carpet.

But many believe the changes do not go far enough.

The profession is pushing for an independent body that could handle complaints against federal judges.

Similar bodies exist in NSW, Victoria and South Australia.

The Law Council has been calling for a federal judicial commission since 2006. Labor backs the move. Even the Judicial Conference of Australia, which represents the nation’s judges, supports the idea, although some experts have flagged potential constitutional issues.

Attorney-General Christian Porter says he is “not closed-minded” to a judicial commission — but, then, he also said that in 2018 and nothing has happened since then.

The Law Council’s Wright says the “time is ripe” now. “We need to bite the bullet and ensure that we’ve got a properly constituted federal judicial commission,” she says. “It would be at arm’s length with the executive government so it doesn’t offend the separation of powers and it maintains judicial independence and integrity.”

The president of the Judicial Conference of Australia, Northern Territory Supreme Court Justice Judith Kelly, says the JCA also backs a federal judicial commission. “We’ve expressed our support for that for some time and we’ve had a policy in place now for a number of years, and that is very much our view,” Kelly says. At the moment, chief judges have few powers at their disposal to discipline judges.

As former High Court chief justice Robert French told The Australian this week: “There’s kind of a nuclear option, which is removal, and other than that there are not direct disciplinary powers.”

Such a body also could consider complaints about other forms of judicial misbehaviour or incapacity. Some judges have been found by appeal courts to repeatedly fail to provide fair hearings, others have been accused of insidious bullying, while some can take up to four years to deliver judgments.

Wright is also pushing for a protocol on judicial behaviour and conduct in the courtroom. She says the Law Council would be happy to contribute to it, but the process should be led by the federal courts.

“We think this is a really important ingredient in this,” she says.

The Law Council also is arguing for changes so the Sex Discrimination Act’s prohibition on sexual harassment also extends to judges and statutory office holders, and barristers and other self-employed people.

“Sexual harassment should be unlawful in all areas of public life,” Wright says.

Heydon, who led the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption in 2014, now faces possible disciplinary action that could result in him being struck off.

He also faces a possible criminal investigation; the Australian Federal Police confirmed on Wednesday it had received a request from ACT Director of Public Prosecutions Shane Drumgold SC to determine if he should face charges.

Heydon’s lawyers, Speed and Stracey, issued a categorical denial of the allegations and said the former judge had informed them that if any conduct had caused offence, the result was “inadvertent and unintended”.

“In respect of the confidential inquiry and its subsequent confidential report, any allegations of predatory behaviour or breaches of the law (are) categorically denied by our client,” the lawyers said.

“Our client says that if any conduct of his has caused offence, that result was inadvertent and unintended, and he apologises for any offence caused. We have asked the High Court to convey that directly to the associate complainants.

“The inquiry was an internal administrative inquiry and was conducted by a public servant and not by a lawyer, judge or a tribunal member. It was conducted without having statutory powers of investigation and of administering affirmations or oaths.’’

Three of Heydon’s female accusers will also seek compensation from the former judge and the government, although the women will need to gain the approval of the Human Rights Commission before civil action can be pursued in the Federal Court.

Media reports this week suggested that concerns about Heydon’s behaviour was some sort of open secret in the legal profession.

However, when the allegations emerged, many were simply gobsmacked — even those women who had led the charge to stamp out bad behaviour or held professional leadership positions.

Many senior female practitioners told The Australian this week Heydon had not been one of those men who had been the subject of quiet warnings from other women.

Those men are still out there, and they just might be quaking in their boots.