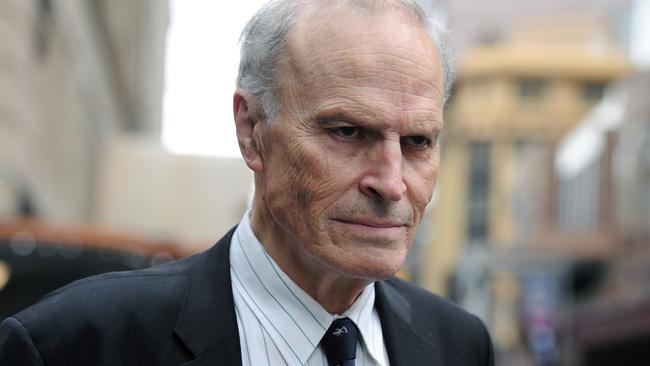

Dyson Heydon sexual harassment inquiry fair and lawful

The former High Court judge declined his chance to answer his accusers and has not explained why.

A workplace investigation conducted by the High Court found that the former judge sexually harassed six employees during his time on the bench. Further, media reports this week have detailed allegations from other senior legal figures of predatory behaviour by Heydon.

A statement from Heydon’s lawyers says he denies “emphatically any allegation of sexual harassment or any offence” and any allegation of predatory behaviour or breaches of the law. Further, “if any conduct of his has caused offence, that result was inadvertent and unintended, and he apologises for any offence caused”.

In a workplace, when a serious allegation is made against a worker, and yes, the former judge was a worker, the employer is duty bound to conduct an investigation and appoint an independent investigator to run it.

Workplace investigations need to be conducted by qualified people, without any connections to either party and with nothing to lose or gain from any outcome.

In this case, the High Court appointed Vivienne Thom. Thom, who has been disparaged as just a public servant and not even a lawyer, is a former inspector-general of intelligence and security, with qualifications in government investigations.

Mostly, lawyers are not appointed to conduct workplace investigations — in this case it could have been especially improper to appoint an investigator from the law because the law is a club and the former judge was a high-ranking member.

In investigations, once the victims and any witnesses have been interviewed, the allegations are collated. Then they are put to the accused, who must be offered an opportunity to respond and given reasonable time to do so.

In this case, a narrative has formed that somehow, the process was not fair to Heydon. This is incorrect. I contacted the High Court. A spokesperson has confirmed that prior to the inquiry, Heydon was consulted about the terms of reference and had input into those.

Then, the allegations were put to him in writing, for his response. However, Heydon then declined to participate in the process any further, and did not provide reasons why. He chose not to respond to the allegations.

So the complaints that the inquiry came to a conclusion without hearing from him are without merit.

In investigations, if a worker declines to respond to allegations put by the employer or their investigator, this is sufficient cause for dismissal. A refusal to respond is a fatally arrogant stance. It is seen as a repudiation of the authority of the employer and their right to conduct the investigation, a failure to help the employer resolve the matter, and a refusal to comply with the employer’s lawful and reasonable direction to engage in the process.

The suggestion this week, that the victims should have been cross-examined by Heydon or his representative to test the veracity of their allegations is outrageous. If this logic is to be followed, then every time an employer receives a complaint from a worker about another worker, they should set up little courts in their workplace, where people can pretend to be lawyers or even appoint lawyers to cross-examine each other.

An employer has no legal basis to demand complainants subject themselves to cross-examination. Importantly, if a victim of sexual harassment was, at the direction of their employer, subject to cross-examination by the person they have accused of the harassment, or that person’s representative, the employer would become liable for any further trauma or injury suffered.

In workplace investigations, once the accused offers their responses, the investigator makes a finding, often with recommendations. The workplace law system is not like the criminal law system. There is no requirement to prove matters beyond a reasonable doubt. Instead, the employer is allowed, providing a thorough and fair investigation has been conducted, and using the “reasonable person test”, to reach a conclusion and deem the alleged to be guilty or not.

In this case, the investigation concluded that Heydon engaged in sexual harassment and the employer has issued an apology to the complainants. The matter may yet end up in the criminal law system.

It is, of course, technically possible that the former judge is entirely innocent of all of the allegations against him. It is possible that every single woman has made the entire thing up. It is also possible that everyone else coming out of the woodwork to report that Heydon’s tendencies were an open secret is making it up too.

The entire thing may be a grand leftist conspiracy to strike a blow against conservatives.

However, I prefer to see this scandal as a workplace issue and not a sad episode in the tiresome culture wars.

In my opinion, the inquiry that made damning allegations against Heydon was conducted in accordance with workplace law and did not lack procedural fairness. Those pretending otherwise are misleading the public.

It was disappointing to hear former prime minister John Howard, via a statement, say “I stand by all of the High Court appointments made by my government” and “Dyson Heydon was an excellent judge of the High Court of Australia”.