Playing a deadly game

The Christchurch shooter was immersed in a world where fantasy mixed with an unhealthy obsession.

Commander Rockwell was a formidable force in the online gaming community. He had spent more than 120 hours playing Battlefield 4 — a war-based first-person shooting game where kills are highly prized — notching up awards for being a “killing machine” and “trigger happy”.

His character was named after George Lincoln Rockwell, the notorious founder of the American Nazi party, Holocaust denier and segregationist.

But unknown to many of his former online gaming friends, Commander Rockwell’s real name was Brenton Tarrant, the white supremacist terrorist behind March’s Christchurch attacks.

It is into this online world — which should have been a hobby of Tarrant but became an unhealthy obsession — that authorities in Australia and New Zealand will trawl as they continue to investigate his background.

PART II: The fight against darkness

Those who played with him through the years make it clear they believe there’s a huge difference between gaming and real-world violence, but at least some he counted as online friends appear to share his toxic beliefs.

He last logged into his Steam online gaming account 10 days before he opened fire at two mosques. On the notorious 8chan message boards he also frequented, he was online just minutes before he killed 51 people.

He carried out those attacks with a GoPro video camera strapped to his head — the vision live-streamed and watched in the same way gamers watch top players of first-person shooting games online.

Tarrant provided commentary of his own massacre as if he was partly in a video game and partly back on the 8chan message boards, playing up to his anonymous online audience.

And when police arrested him on a Christchurch street minutes after he fired his last shot, there was one thing he wanted to know.

“How many did I kill?”

For Tarrant, it was not an odd question to ask.

In the game Battlefield 4 alone, he made 4198 kills by the time he last logged out of the game a year ago.

Of those, 503 were from headshots, his longest “kill-streak” is recorded as 25 and he took 36 “dog tags” — by killing other players in “knife attacks”.

He started playing the first-person shooting game — where players can play as the US, China and Russia in matches involving up to 64 players — in Grafton in 2013. That was just one of more than 120 games he has owned since 2004 where he would shoot “soldiers”, zombies and terrorists for hours on end.

It was into this online world — as well as the 4chan and 8chan message boards — where Tarrant descended following the death of his father, Rodney, in 2010.

“Gaming is addictive because everyone is a winner,” his mother, Sharon Tarrant, told the New Zealand Herald last month. “You are not learning about the real world where things don’t go the way you want it. You have to work hard and communicate with each other, but young people have lost that ability and go into spaces that are psychologically harmful.”

She told the newspaper she tried to convince her son to cut himself off from the “dystopian sorts” he was meeting online but it didn’t work.

“All of those people on the dark web encourage each other, it’s frightening.”

Alt-right meetings

The Australian has delved deeply into Brenton Tarrant’s online world, tracking him across games, message boards, websites, usernames and social media accounts.

It has uncovered an anonymous claim made in the days after the attack that Tarrant attended a meeting of alt-right figures at a Sydney pub in 2017, after meeting an organiser on the “book club” forums of controversial US neo-Nazi website the Daily Stormer. If true, it would be the first known evidence of physical contact between Tarrant and members of Australia’s far right.

“We only exchanged 3 messages and met for once for about 3 hours at a pub,” the anonymous poster wrote on 8chan on March 24. “He only mentioned that he travelled a bit, nothing specific. His favourite subject was crypto (cryptocurrency) trading. He seemed to have had some pretty advanced knowledge. Definitely above 120 IQ.”

The poster subsequently claimed to have been a member of the alt-right Dingoes crew, made infamous by their podcasts, and said: “I for one salute this courageous c..t for his heroic efforts.”

Attempts to confirm his presence at such a meeting have been unsuccessful. But The Australian found earlier posts from the archives of the Daily Stormer website and 4chan that suggest members of the Daily Stormer book club and the Dingoes organised “meet-ups” in Sydney.

And, according to the 8chan post, Tarrant had used the name “shitpostwaffen” on the Daily Stormer forums — a name that was referred to in another 8chan post praising Tarrant’s actions in New Zealand that appeared days earlier. That was just one name linked to Tarrant, who has also gone by Barry Harry Tarry, ferretbiter and ferretlicker.

On gaming platform Steam and on 4chan — the message board abandoned by more extreme posters in favour of 8chan after 4chan began cracking down on some of the content being shared — he hid much of his horrendous virtual hatred in private communications and on “/pol/” — the “politically incorrect” boards.

Isolated from anyone who could be referred to as a close friend, a partner or a lover, this is where Tarrant found a home.

‘Best bunch of cobbers’

It was 8chan’s /pol/ board where Tarrant felt most comfortable announcing his attack.

He did have a Twitter account with few followers where he shared links to his manifesto, photos of his guns and other assorted links. He also live-streamed his attack on Facebook.

But it was 8chan and its anonymous users who made sure it reached a wide audience.

“Well lads, it’s time to stop shitposting and time to make a real life effort post,” Tarrant posted on March 15. “I will carry out and (sic) attack against the invaders, and will even live stream the attack via facebook.

“The facebook link is below, by the time you read this I should be going live.”

He thanked the others on the forum, describing them as “top blokes and the best bunch of cobbers a man could ask for”.

Both the post and his manifesto nod to the language and vulgarity of the now-defunct forum, which was a hotbed of sexist, racist and bigoted comments, all made anonymously. Even when he first appeared in a Christchurch courtroom — where he has since pleaded not guilty to 51 murders, 40 counts of attempted murder and one terrorism charge — he flashed the “OK” symbol with his hand — a gesture that 8chan users have successfully linked to the white supremacy movement to provoke reactions in others.

When 8chan was knocked offline last month after another user, Patrick Crusius, inspired by Tarrant, killed 22 people at a Texas shopping centre, many of its members returned to 4chan and other forums to share their views. It was also on 4chan that “Alan”, who claimed to be from Russia, shared a macabre trophy last month: a handwritten letter from Tarrant, sent from his New Zealand jail cell.

The letter was initially dismissed by other 4chan users as fake, but after prison authorities confirmed it was from Tarrant, “Alan” was being widely praised on the website.

It is written as though it were to be read by a child. He listed his three favourite places in Russia and his favourite Russian songs. He also wrote about his political beliefs, describing his views as being most like those of 1930s British fascist Oswald Mosley.

And despite writing six pages about himself, his travels and his beliefs, he asks no questions of “Alan” or shows any interest in ongoing correspondence other than to say: “In the future, if you wish to write or contact me you can just email the prison.”

It is nearly impossible to trace the authors of posts on either 8chan or 4chan.

But there has been some spillover of Tarrant’s views in his social media accounts.

The Australian uncovered connections to members of the Australian far right in the days following the attack, including to a Gold Coast machinist, Marcus Christensen, who received a five-star review from Tarrant on his business’s Facebook account. Christensen, who had a mural of Mosley in his workshop, revealed Tarrant had been “in the community for over two years”.

Days later, the ABC revealed Tarrant had used his Facebook account to repeatedly praise far-right extremist Blair Cottrell in 2016.

But he ramped up his public social media posts in the days before the attacks. According to an online archive of his Facebook page, between December 30 and the start of March, only four posts were created and not hidden from public view: a photo of a Romanian cemetery and three photos taken in Pakistan.

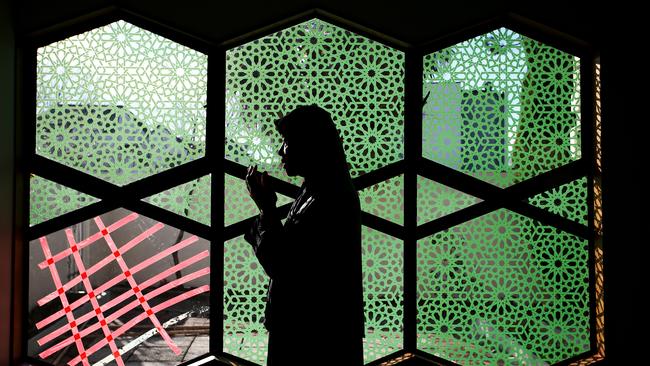

But on March 13 alone, he added at least 146 photos and two videos to a Facebook album titled “Open in case of Saracens”. “Saracen” was a word used by Christian writers in the Middle Ages to describe Muslims during the Crusades.

Games without friends

Tarrant was sparing when it came to adding gaming friends. One database that collects historic Steam data suggests that since signing up to the platform in 2004, he has had about 30 friends in total — although the number may be higher as his profile is partly private. Only one account now lists “Commander Rockwell” as a friend.

Besides Battlefield 4, online logs record Tarrant as playing first-person shooting games such as Team Fortress 2, Half-Life 2 and Killing Floor.

One gamer, the Melbourne-based “Adonikam”, was briefly and unknowingly friends with Tarrant on Steam about nine years ago after meeting in a zombie-based game.

“I may be confusing him with someone else … if it is who I’m thinking of we probably were running together in the DayZ Arma 2 mod, which was like a zombie-survival kind of game,” he said.

“It was essentially just like a game where you had to survive in the woodland, but there were zombies there trying to kill you and other players would also try to kill you for your gear. I would have been playing with him as a teammate because the only way to get someone’s information in that game is to say it over a microphone.”

Another former online friend, New Zealand-based Steve Crossland, said he never knew the person behind the Steam account but guesses they connected in one of the few non-racing car games he played, Battlefield.

“I hadn’t seen him for a long time — like years — on Steam. But I had no idea,” Crossland said.

“To be honest, back then it was probably through a Battlefield game. I didn’t know it was, but you’d play against someone. And after the game they can look you up and add you as a friend or whatever if they had a good game. So that’s probably what it is.

“I just remember the name — I used to see him. When you’ve got a Steam contact, every time they go online it pops up. You’d see the name all the time but not necessarily know them.”

It’s a sentiment shared again and again by those who dealt with him in the online world he substituted for real-life connection — every person who spoke with The Australian said they didn’t really know him.

Forum talking point

Months after the attacks, members of the NZ Hunting and Shooting Forums were still in shock.

On the day of the attacks, one “thread” of posts about the attacks was deleted by administrators. The reason for the deletion: “The person in question was/is a member here.”

Not long after that, another member of the forum claimed to have met Tarrant at the Bruce Rifle Club near Dunedin, where he found him “pleasant to talk to, no profanities, well spoken, polite with no mentioning of racism or political views”. That user did not respond to a request for comment.

Tarrant’s online identity has been kept secret on the forum but users have continued to discuss his activities. One user said in June that he had spoken with a detective about his own trading of firearm parts with Tarrant.

“He bought and sold quite a bit of shit, so his entire transaction history was trawled through according to Mr Detective,” he said. “(It) was a legal transaction, just my little brush with the devil. Ironically, the mags I bought off him are now the only legal centerfire mags I now own.”

There was one user who showed an interest in only two items being discussed for sale on the forum. One item was a magazine that can hold 30 rounds, posted for sale in February last year, for $65 bought in person cash or $70 if it needed to be sent to the buyer. The other, posted on the forum on December 28, 2017, was a special drum magazine that could hold 60 rounds.

Both were designed for use with the deadly AR-15 assault rifle.

Photos of similar magazines were posted online by Tarrant before the attacks, covered in white handwriting, along with his own AR-15.

It’s unclear whether the user was in fact Tarrant. On the forum, he only offered his username: CommanderRockwell.

Praised as a ‘saint’

Tarrant rarely offered his real name online, yet he has now become a haunting figure, lurking in the darkest corners of the internet. He has been named as an inspiration by a series of right-wing extremists who have carried out their own attacks around the world since the Christchurch shootings.

The former 8chan crowd praise him as a “saint” — but fail to acknowledge that he is a loner who failed to leave an impression on many of those he met.

But from that solitary life behind a computer screen, cutting a sad figure in the cold of New Zealand’s South Island, Tarrant connected with one teenage boy in Sydney via the gaming platform Steam.

How they found each other in July last year is unclear. But what is apparent is their shared love of far-right ideology and 8chan’s vitriolic form of discussion.

“The Professional Kebab Removers” was the name of the group created by the boy on Steam the day after the Christchurch attacks. The group’s profile picture was an image of Tarrant and a crude drawing of a British crusader.

On its page, which now has been removed by Steam, links to Tarrant’s video of the attack, his manifesto and the 8chan post he put up minutes before the shootings were posted.

The group had only one member — the teenage boy known only as Antipodean, who The Australian understands dropped out of a inner-western Sydney school about two years ago.

Another student, whose mobile number was briefly shared by Antipodean on Steam in 2015, said he had no idea about the boy’s beliefs and barely had anything to do with him. Among the other posts or usernames the boy has used are “Gas the kikes race war now” and “Ching Chong”, as well as photos of people like Mosley and Nazi soldiers.

The student who went to school with him said he intended to report the boy to police, and declined to provide any further information to The Australian.

How Tarrant came into contact with the boy — who The Australian unsuccessfully sought for comment — is unknown but one former Steam friend said the 4chan message board played a part in his connection to the Australian.

“I don’t know which it could be and it’s annoying me because the name ferret licker is ringing quite a big bell,” Scotland-based programmer Kyle Motherwell said of how he connected with Tarrant.

“I either met him in game whilst on Steam and ended up with him on my friends list or I met him on 4chan’s /v/ board — which is a place for discussing games.”

Motherwell had no idea about the gamer’s identity or political beliefs — if he did he would never have accepted him as a friend.

His connection to Tarrant is believed to have occurred several years ago, possibly before the Australian became radicalised, and online records suggest they stopped being online friends at least a year ago.

“I don’t recall ever interacting with him, but if I did he was most likely behaving normal,” he said. “Based on his manifesto, I doubt he would if (he) ever advertised it much outside of anonymous boards.

“Pol is a place that is full of people like him.”