Inside the hate-filled mind of a mass murderer

Even before police gave her the news, Janna Ezat knew her son was dead.

Even before police gave her the news, Janna Ezat knew her son was dead. She had spent the day of the Christchurch shooting at the hospital hoping for news of Hussein. Her heart would lift every time a hospital official emerged to read a list of the survivors, then sink again as she realised her son’s name was not among them. This went on for hours.

Calls to Hussein’s mobile in the minutes after the attack went unanswered, so in desperation Ezat and her husband, Hazim al-Umari, drove to the Al Noor mosque — or they had tried to.

A cordon of heavily armed police held them back. They walked across nearby Hagley Park to the Christchurch Hospital, hoping Hussein might be among the injured. Scores of panicked family members had the same idea.

PART III: Playing a deadly game

The city of Christchurch was in lockdown and those who had flocked to the hospital found themselves trapped there. Staff set aside the cafeteria to accommodate them. There were dozens of them. Some were crying, others were breaking down. A few had the blood of the dead on their clothes. In the corner police had set up a table and chairs to handle the crowds. After a few hours someone printed out a list of the wounded and stuck it on the walls.

“It was like stepping into a movie scene,’’ Hussein’s sister Aya al-Umari tells The Australian. “It was like floating between reality and fantasy.’’

At 6pm the lockdown ended and the Umaris headed back to the Al Noor Mosque. They knew they had no hope of getting through. The plan was to scour the side streets looking for Hussein’s car. That might give them a clue.

It was the last throw of a desperate family and in her mother’s heart Ezat knew it was futile. Hussein was a fit, handsome young man, known for his gallantry and self-confidence. Ezat used to joke that living with Hussein was like having a policeman in the house.

“The day of the shooting, before we knew if he was dead or alive, my husband and I were chatting to each other and said, ‘We know our son. He will never sit or escape. We know he will attack or he will do something’.”

They were right. Hussein was in the front row of the Al Noor mosque as Brenton Tarrant, 28, walked to the threshold and began shooting. As others fled, Hussein stayed. Footage taken by Tarrant and live-streamed on Facebook appears to show Hussein lingering by the doorway, perhaps in the hope of ambushing the killer. As Tarrant rounds the corridor into the mosque’s main chamber Hussein can be seen reeling in surprise, before being sprayed with bullets.

“Everyone was running forward and away and one of the only ones who turned to face the gunman was Hussein,’’ says his friend Ali Adeeb. “He was an amazing guy, kind soul, did everything the right way. He was the only one to go towards the gunman.’’

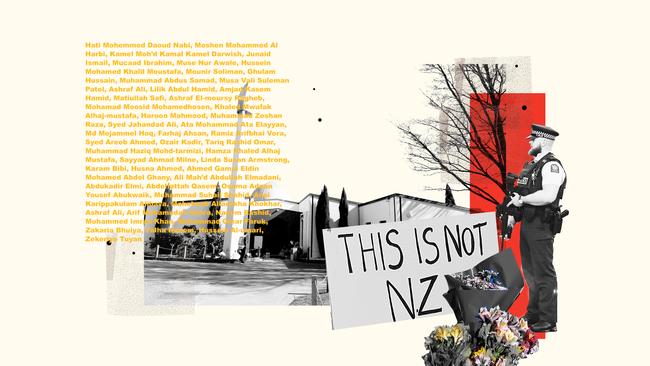

Tarrant attacked two targets that day — the Al Noor Mosque and the nearby Linwood Islamic Centre. He killed 51 people and injured 49. Most of the damage was at Al Noor, where the bodies lay in gathering piles on either side of the building’s main prayer room. A lucky few escaped through the plate-glass windows on either side of the mosque.

Mustafa Boztas had been in the mosque for a few minutes when the shooting started. He rushed to the window and as the bodies began to fall he lay still, playing dead. As a bullet pierced his leg and travelled through his midsection and into his liver, a strange calm overcame him.

“I thought of my parents and straight after I realised: I am at the mosque. I became normal, not scared. Calm. I figured I was to be a martyr. When I realised that I had no fear, nothing,’’ Boztas tells The Australian.

Boztas escaped. He ran down the side alley of the mosque where he came upon the body of a teenage boy with multiple gunshot wounds to his torso. Boztas tried briefly to revive him with CPR before giving up and closing his eyes. The boy was still clutching a mobile phone.

“I picked it up and I realised it was his mum,’’ he says. “She was crying. She’s asking for her husband and her son. I said, ‘I have no clue. I am new to Christchurch but there’s one young kid lying down here’. She started screaming. I put the phone down and I had to run.’’

How many did I kill?

When police took Brenton Tarrant into custody 19 minutes after he fired his first shot, the Australian had only one question for officers: “How many did I kill?” A source close to the arrest says Tarrant asked the question repeatedly, horrifying police who were just beginning to come to terms with the full scale of his violence. Tarrant had committed New Zealand’s worst mass murder, but in his mind it seems he was already measuring himself against his heroes — Anders Breivik, the rightwing terrorist who killed 77 people in a series of terrorist attacks in Norway in 2011 and Dylann Roof, the Charleston church shooter who killed nine African-Americans in 2015. The body count is the metric of modern terrorism.

Forcing political change through violence, the tactic of older groups like the IRA and the PLO, has given way to unbridled killing. Tarrant’s dream of a racially purified West is identical in ambition to the worldwide caliphate dreamed of by Islamic State. Both are utopian fantasies that justify any degree of suffering in their cause. Violence, once a means to an end for terrorists, has become an end in itself. “I only wished I could have killed more invaders,’’ Tarrant wrote in his manifesto, in a Q&A section that anticipated questions about his attack.

Among the many questions to be considered by the royal commission set up to investigate the Christchurch attack, is this: How did a man who posted regularly on right-wing hate sites, who donated money to overseas extremist groups, and who was known to be acquiring large numbers of high-powered firearms, escape the attention of security authorities?

The failure to flag Tarrant as a potential threat would appear to be a straightforward case of intelligence failure. His travel patterns alone might have aroused suspicion. The question is: whose failure was it? Tarrant was an Australian citizen living in New Zealand and travelling all over the world. The dots were there to be joined but because they fell across jurisdictions in Australia, New Zealand and Europe, nobody appears to have joined them.

Tarrant had some contact with right-wing figures in Australia. He had a high regard for Blair Cottrell, the leader of the United Patriots Front, a far-right group at the forefront of the Bendigo mosque protests four years ago.

“Never believed we would have a true leader of the nationalist movement in Australia, and especially not so early in the game,’’ Tarrant wrote on the UPF’s Facebook page in 2016.

Pastiche of hate

But Tarrant’s real inspiration came from the racist ideologies that have roiled Europe, spurring the growth of far-right parties and extremist movements. He was particularly fascinated with the Identitarian movement, a neo-fascist group that originated in France in the 1960s and which has since spread across Europe, fuelled by rising concern over migrant numbers.

Identitarians subscribe to “the great replacement’’ theory, a term Tarrant gave to his own manifesto. Proposed by French political scientist Renaud Camus in his 2011 book of the same name, it argues white Europeans are being bred out of existence by Muslim migrants by virtue of their higher birth rates.

Identitarians don’t field candidates in elections and their membership in France only runs to about 1000. Their goal is to influence public opinion. They are opposed to assimilation and believe migrants should be forcefully repatriated to the country of their birth. Identitarians do not consider themselves racist, per se. Rather, they see all races as having their own place on Earth.

“In my mind a rainbow is only beautiful due to its variety of colours, mix the colours together and you destroy them all and they are gone forever and the end result is far from beautiful,’’ Tarrant wrote.

Identitarianism has been implicated in some of the worst acts of right-wing violence, Tarrant’s included.

Tarrant donated to two such groups — Generation Identity in France and the Identitare Bewegung Osterreichs, its Austrian affiliate. The sums were small., no more than $US2500 ($3648). But to a fringe-dwelling movement like the Identitarians they were substantial. The IBO’s leader, a smooth-talking hipster named Martin Sellner, emailed Tarrant, thanking him for his generosity and inviting him for a beer or a coffee should he ever find himself in Austria. There is no evidence the two ever met, although a source close to Tarrant says he spoke of changing his travel dates in Austria by four days so he could meet someone “really famous”.

Jean-Yves Camus is a French political scientist and an expert on far-right groups, including the Identitarian movement. He agrees Tarrant was influenced by Identitarian ideology but cautions against assigning too much weight to them. He says Tarrant’s beliefs were a pastiche of Nazism, neo-Nazism and other right-wing ideologies. This, he says, is typical of the digital generation of extremists, who are less doctrinaire than their predecessors.

“Those people don’t stick to one ideology,’’ Camus tells The Australian. “They take pieces from the Identitarian movement, the fascist movement, the neo-Nazi movement. They borrow from the United States, from Europe. This you can do right away from the computer. You don’t have to go to a bookshop, you don’t have to be a member of any group.’’

The constellation of slogans, memes and names Tarrant inscribed all over the rifles he used in his attacks speaks to the breadth, or rather the narrowness, of Tarrant’s travels across the right-wing ideological landscape. “Kebab remover’’ was a reference to notorious Serbian commander Radovan Karadzic, who massacred Bosnian Muslims during the Balkans conflict. “14’’ referred to the so-called “14 words’’ of notorious white supremacist David Lane. (“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children’’) “1565’’ was the year the Ottoman Turks were repelled in the Siege of Malta.

To Tarrant these were symbols of a carefully thought-out philosophy, which he hoped would explain his actions to the world. They were a cut-and-paste job of rightwing memes, Old World bigotry and recycled hate speech. Tarrant’s “ideology” was as tired as it was nasty.

Life in New Zealand

Tarrant moved to New Zealand in 2017. He rented a modest one-bedroom flat in Dunedin, on New Zealand’s South Island, where he kept to himself and made little impression on his neighbours. People would see him walking to and from his car, usually with a gym bag in hand. The previous tenants had been party animals and one of the first things neighbours noticed about the new resident was his bin was always empty. It seemed Tarrant wasn’t much of a drinker.

The most notable thing to happen to Tarrant was a minor bingle caused when a neighbour’s car rolled into the back of his. It was the most trivial of accidents but when Tarrant approached the car’s owner she bellowed abuse at him. As the epithets rained down a neighbour who witnessed the exchange says Tarrant, who was blameless, remained completely unflappable.

“He didn’t even square off,’’ says the neighbour, who asked not to be named. “His body language was calm, totally calm.”

Hunting, fishing, hiking and shooting are serious pursuits in Dunedin, and Tarrant seems to have been attracted to the city’s robust outdoor culture. Dunedin boasts no less than six gun clubs. As you drive through the main drag, huge gun shops dot the strip malls to your left and to your right.

Tarrant was a member of at least one of those clubs, the now defunct Bruce Rifle Club, about 20 minutes south of Dunedin. On a thin ribbon of land that stretches off into the hills, the range is buttressed by a creek on one side and thick bush on the other. It is an isolated, beautiful place; eerie and silent, save for the occasional rustle of animals and the whistle of wind through the brush. Tarrant came here often, honing the skills he would use to deadly effect on March 15. When The Australian visited, the range was empty and calls to the club’s president and secretary were not returned. The club has shut up shop and its members want nothing to do with Tarrant.

Tarrant owned at least five high-powered weapons, all of which he bought legally. At least four were purchased online. Peter Breidahl visited the range back in late 2017. An experienced hunter and marksman, Breidahl says he was horrified by what he saw. “From top to bottom those people were wrong. They were blatantly Islamophobic,’’ he tells The Australian.

Fixation with Port Arthur

Breidahl recalls one conversation with a group of shooters, one of whom he says was Brenton Tarrant. The subject was the 1996 Port Arthur massacre, a staple of right-wing conspiracy theorists who believe Martin Bryant’s shooting was a government plot aimed at robbing gun owners of their firearms.

Exhibit A in this theory is Bryant’s unusually high “kill ratio”. That is, the high number of people killed as against the relatively small number injured. It is a wild hypothesis, demonstrably wrong, and even Tarrant seems to have given it short shrift. Instead he appears to have used the Port Arthur massacre as a tactical learning experience.

“He was talking about how Martin Bryant had cornered people in the booth and how he managed to make so many head shots in such a rapid pace,’’ Breidahl says.

“This is a guy who had clearly studied how Martin Bryant had done it in great detail.’’

Breidahl’s recollection could not be verified and other members of the Dunedin shooting community tell a different story. They reject the notion that the Bruce Rifle Club was overrun with weirdos and say there was nothing to flag Tarrant as dangerous.

“All I’ve heard about the guy is that he was always very helpful, he didn’t turn up in Rambo-style gear,’’ says John Fooks, a clay-shooting coach in Dunedin who heard of, but never met, Tarrant. “He just turned up as an ordinary guy. He would help set things up. He would help tidy things up at the end of the shoot. Just what any other club shooter would do. He didn’t stand out as a raving lunatic.’’

On New Year’s Eve 2018, Sharon Tarrant arrived in Dunedin with her partner, Gerald Tory. It was the last time Sharon Tarrant would see her son outside Auckland Prison, where he now resides. The visit was brief, just two days, and for Sharon Tarrant it was more intervention than a holiday. Sharon Tarrant wanted to know everything about Brenton’s life in New Zealand. She had become desperately worried about her son, who had left Grafton nearly a decade earlier and save for a few rest stops hadn’t been home since. His endless travelling had left him socially isolated. His politics had become hate-filled and bitter. His racism was, as one source close to him put it, “at full throttle”.

During the two-day trip Tarrant argued constantly with his mother.The Australian has been told he refused to eat at restaurants run by Muslims, and railed against Turkish people, who he regarded as being at the forefront of Islam’s assault on the Christian West. He was just about out of money. After nearly a decade on the move the walls were closing in.

It didn’t matter. The loose plan he had long harboured was finally taking shape.

Restoring hope

Five months after the Christchurch attack and the Al Noor Mosque has been completely restored. The windows terrified worshippers smashed to escape have been repaired. The divots left by the barrage of rifle fire have been patched over. The blood has gone from the carpets. When The Australian visited most of the survivors from that day were in Saudi Arabia making Haj, the holy pilgrimage to Mecca. Their travel was funded by the King of Saudi Arabia, one of the many gestures, large and small, that have been showered on survivors and their families.

In the mosque’s main chamber, a few feet from where Tarrant stood as he pumped round after round into his victims, a handful of worshippers pray quietly. Behind them a toddler scampers impishly, peering out to where Bostaz found a dead 15-year-old boy whose last terrified act was to call his mother. Sunshine floods the room. The faithful murmur their prayers and smile politely at visitors.

The race war Tarrant hoped to ignite with his act of terrorism has yet to materialise. The hatred that drove him has been met with compassion, even forgiveness. “God will do whatever he wants with him,’’ Hazim al-Umari says of the man who murdered his son. “But for us, as Muslims, forgiveness is the highest degree of belief.’’

The only visible sign Tarrant was ever there is the shrine at the mosque’s gate.

Where Tarrant left bullets, New Zealanders have left flowers.