‘People shouldn’t feel embarrassed or ashamed to say No to Indigenous voice to parliament’: Kerrynne Liddle

Stolen Generations, family violence, child removal - Kerrynne Liddle understands the traumas in Indigenous communities because she has witnessed them first-hand.

South Australian senator Kerrynne Liddle is striding through the streets of Adelaide remarking on the scattering of Yes posters she has noticed springing on businesses and charities, at sporting venues and other public spaces.

It irks this Arrernte woman, born and raised in Alice Springs, that these bodies are campaigning publicly for a Yes vote at the upcoming voice referendum, assuming their staff, shareholders and customers are all of the one mind. Do people want political messaging on their morning milk run or while dropping their kid at weekend sport, she wonders.

Would employees or members of these organisations feel comfortable raising doubts or revealing they were inclined to vote No? “It’s a way of silencing people and I don’t like it,” she declares.

The first-term politician is heading towards Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, a body she once chaired, and on the approach Liddle notices Yes signs at the front door before it’s opened by interim chief executive and Yes advocate Phil Saunders.

As we browse the art being catalogued in a stocktake, he proudly tells her the national campaign for Yes23 was officially launched here on a hot February day before a crowd of about 600 people.

Instead of nodding diplomatically and staying shtum, Liddle seizes the moment and says what Saunders already knows. I’m a No, she declares in a way that invites discussion with no expectation that she can be persuaded to change her mind.

Saunders, a Bunganditj, Gunditjmara and Narungga man tells me he doesn’t understand why anyone would actively say no – that the voice is a step in the right direction that should be seen as a unifying moment for Australia. It’s an opportunity, he says, a gift for generations to come.

It’s clear that Liddle and Saunders will agree to disagree as they hug goodbye.

Are these exchanges awkward, I ask Liddle later? “Not at all,” she responds. She has thought long and hard about her position and she’s not afraid to raise it. “People shouldn’t feel embarrassed or ashamed to say what they feel.”

Saunders agrees on this point. “She’s entitled to her opinion. She’s one person in the whole tapestry of this debate,” he says.

“I deeply respect Kerrynne as a woman and a person doing great things. She happens to be an Aboriginal senator, but that’s not the crux of it. I respect her for her views even though I don’t agree with them.”

If only the entire voice debate were conducted in such a cordial fashion.

When Liddle won her Liberal Senate seat at last year’s federal election she had already decided she couldn’t support a constitutionally enshrined voice so it was something of a relief when her party landed on a decision to support recognition but oppose the government’s model for the voice.

Liddle’s professional experience – as a journalist with the ABC and Channel 7, small business owner, board member of various organisations as well as serving on the councils of the University of Adelaide and University of South Australia – is well known. She was also, briefly, a member of the Labor Party (“I worked out pretty quickly it was not the party for me”).

At 183cm tall she has a presence when she walks into a room and fixes people with her direct, confident gaze. People describe the 56-year-old as no nonsense and outcome focused.

Her lived experience, however, is less well known and that’s because she finds it difficult to discuss.

Liddle’s mother was a child of the Stolen Generations, taken from her family because she was fair-skinned. Her older sister was killed in a domestic violence incident. Liddle and her partner, Vince, fostered a child with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. She has witnessed and lived with the issues that Yes proponents say the voice aims to fix. How, then, did Liddle arrive at such a firm position against it?

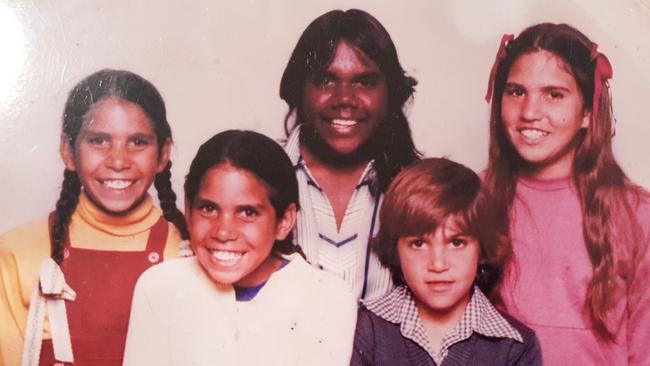

A pile of photos fans out on the table, the sort of faded, filter-free images that speak to a different time. There’s her mum, Jean, with the Queen and with Prince Charles, or smiling on the day of her marriage to Kerrynne’s dad Geoff, a construction worker whose hard work and sense of fairness permeated the family.

There are her siblings: Jamie, a captain with an international airline; the twins, Leanne, South Australia’s first female Indigenous police officer who went on to work on justice issues in the Northern Territory, and Lynette, an environmental scientist.

Older sister Jenny appears in one of the photos. She worked in education and Liddle’s voice breaks as she points to her sister and adds that she has passed away.

Tears threaten as she says it’s not something she feels able to discuss. “These things never leave you,” she saying, confirming that her sister was killed in a family violence incident. “The system failed her too.”

It’s the second time during our interview that her adviser has reached for the tissues. Liddle tries to keep emotion out of her delivery but it breaks through when talking about family, and the death of her mother – a nurse and social worker who worked to improve the lives of others in her beloved Arrernte country in central Australia – last year is still raw.

“My mum identified as part of the Stolen Generation but she used to say that experience didn’t define her,” she says.

Jean didn’t like to speak of that time. There are things her daughter doesn’t know, subjects that could not be explored with her mother or grandmother of those terrible times when Jean and her brother were removed from a loving home.

“Her case is quite well recorded, that they took her from her home and from parents who were looking after her very well. Mum and her brother, because they had slightly lighter skin, were taken to an elite boarding school in Melbourne, different boarding schools,” Liddle says.

“When you are separated from your mother under those circumstances it’s never, ever the same. Her mother was really affected by the fact that she had children, and then she had nothing. She didn’t know where her kids had gone.”

I ask how she feels now about what happened to her mother.

“Um, well, those things have a huge effect on … there is an intergenerational effect on that. It was an important part of her life and she dealt with it as best she could.

“She valued the family unit, she was incredibly protective and possessive of her children, and she took no prisoners. She didn’t have a big circle of friends because that’s what happens to people who could lose their friends, lose their family, lose their community, so those things are really important.”

Liddle veers quickly to safer ground, the lessons learnt watching her parents “show up, stand up, speak up time and again with courage and conviction”.

Parental and individual responsibility, reward for hard work, being the master of your own destiny – Liddle mentioned these in her first speech to the Senate because they are tenets she holds dear too. Hers wasn’t a materially privileged upbringing but she had the benefits of a stable home where education, family, connection to culture and community were paramount.

She pulls out class photos from Alice Spring High School and notes the number of Aboriginal children in her class. “There was a lot of success in educating kids then,” she says.

What has changed?

“I think it’s expectations. When I was growing up it was the norm to go to school and those people I went to school with did pretty well.

“In those days there was a police officer in the school, there was a nurse in the school, and the liaison officer would work with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal families. My mother was a liaison officer; if your kid wasn’t in the school she’d be knocking on the door to ask why.”

The family home was busy and it was a haven for other kids who needed safe harbour. So it was natural that as an adult Liddle would open her home to children in need too.

We look at a photo of three children – two are hers and a third is a little boy, “Joe”, an Indigenous child with complex needs including FASD whose parents were unable to care for him.

He had been cycled through various placements in the child protection system when Liddle and her partner Vince took him in, in a type of informal shared care arrangement with a family friend. She helped care for her sister Jenny’s child, too. They’re now terrific adults, she says, noting that Joe completed his certificate 4 in gardening. “That’s a big outcome for a FASD person.” Even when he struggles with poor mental health he has “handrails”, she says: stable people who support him. “That’s what’s important.”

As opposition child protection spokeswoman, how does she feel about the debate on Indigenous foster children and policies that state they should be placed with non-Aboriginal carers only as a last resort?

“The most important thing is that children are in a safe home. That’s the priority. You find a way to keep (cultural) connection. It may not be ideal but you find a way. The central thing is that kids have stable care, a sense of belonging somewhere.”

Early support for struggling families is vital, she says. “Nobody wants to lose their children. Nobody wants to harm their children. Having supports in place early, and people who are not fearful of asking for help, is critical to support children and parents.”

Liddle is careful with her words during our interview and emphasises that she doesn’t like to be defined by race. “I don’t come with an aspect that is just Indigenous,” she says. “I come as a mother, a female, a person who has run a business, a person who has been a Joe Citizen. I fear that there’s too much focus on race and that’s to our detriment.”

She wants to see the lives of Indigenous people improved and the yawning gaps to be closed. But she fundamentally disagrees with a constitutionally enshrined voice because she says it’s not clear how it will work or what it will achieve in a practical sense. She’s worried about permanence, about another layer of bureaucracy.

“I will always recognise these people have special rights and interests based on their areas of responsibility and their identity,” she says, gesturing to a photograph on her wall of three Indigenous elders.

“Let people be engaged on matters that are of interest to them but you don’t need to put that in the Constitution.”

Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney says it is important that the voice is a permanent, consistent body protected by the Constitution, safe from future governments that might abolish it at the stroke of a pen.

It would be focused on making a practical difference for the most disadvantaged people across key areas such as housing, jobs, health and education, and would be chosen by local communities for local communities. To vote Yes is an act of patriotism, she says.

“We need new perspectives to old challenges, perspectives that are connected to communities,” Burney said in her National Press Club address on Wednesday.

“We have everything to gain and nothing to lose by supporting the voice. Because the voice will be a mechanism for government and parliament to listen. It will be like a resource of local knowledge and solutions that can help us make better policies.”

Liddle counters that consultation and advice on matters that affect Indigenous communities already happens through existing forums and frameworks, going on to list the commissioners, ambassadors, advocates, working groups and expert panels tasked with providing input to governments.

“You can’t argue that this isn’t happening already and that it isn’t resourced to happen, and that expert people aren’t embedded in frameworks to continue to provide advice on these things. If we’re not leveraging enough from those groups, then look at the framework in which you get the information and input so it improves.”

She takes aim at government departments but also Aboriginal community-controlled organisations. “Go your hardest if you think that this pushback is racist,” she said in her first speech.

“I’ll continue to call out the double standards and disturbing assumptions and what I call reverse racism.”

If it were in her power to make one big change now for the benefit of Aboriginal people, what would it be? She goes immediately to her experience in business and governance: ensuring that new and existing programs and policies achieve what they are funded to do.

“I’d require all funding agreements to have measurable and integrated targets so they couldn’t operate in silos,” she says.

Responsibility and accountability. She repeats these words often in our interview, and it extends to her own side of politics. She’s critical of former Liberal MP Ken Wyatt, who recently hit out at Nyunggai Warren Mundine and Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, saying neither of the prominent No campaigners had been able to deliver meaningful solutions for Indigenous people despite having been in positions of influence in the past.

“Well hello, you were the minister and then the minister for Indigenous health,” Liddle says of Wyatt. He was a minister in your party during a long stint in government, I point out.

“I know. I don’t care whose party it is, we all need to be accountable.

“I can’t be responsible for (past decisions) but I am responsible for what I do and say, and I will always advocate for greater accountability along the supply chain. It’s in my DNA, it’s what informed me my entire life.”

How does she feel about the way the debate is proceeding?

“It’s terrible.’’ Is she worried about the aftermath of a No vote?

“No, I’m more concerned with us heading towards a referendum when the polls are saying 50 per cent – that’s a nation divided.”

She stops and thinks. “Regardless of result, there will be an expectation on all of us that there needs to be change. There is an expectation that the lives of people will be improved as a result of this process.”

On this, she is in complete agreement with Saunders, the staunch Yes advocate. “Whether it’s a Yes or No vote, there is still plenty to be done,” he says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout