With the greatest respect, ‘Yes’ voice camp needs to think like a conservative

The PM and co won’t win mainstream support for the Indigenous voice to parliament referendum by lecturing or admonishing opponents.

One of my best mates, like me, was on board with the Adelaide Crows from their inception, as were his three boys from the cradle onwards, but one of them now captains Port Adelaide.

There are deep-seated rivalries here, commitments so strong they foster enmity. But our love of each other, and the great Indigenous game, overcomes visceral intolerance and we all get along.

One of those fine Collingwood fans I count as a friend is senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. To give a sense of our familiarity, most of you knew her only as Jacinta Price until at our place for a meal one night her husband, Colin, asked me why I didn’t use Jacinta’s “skin” name. We discussed her preference, and I began using Nampijinpa Price on air. Before long my Sky News colleagues were checking pronunciation and using it too, and soon even the ABC followed suit.

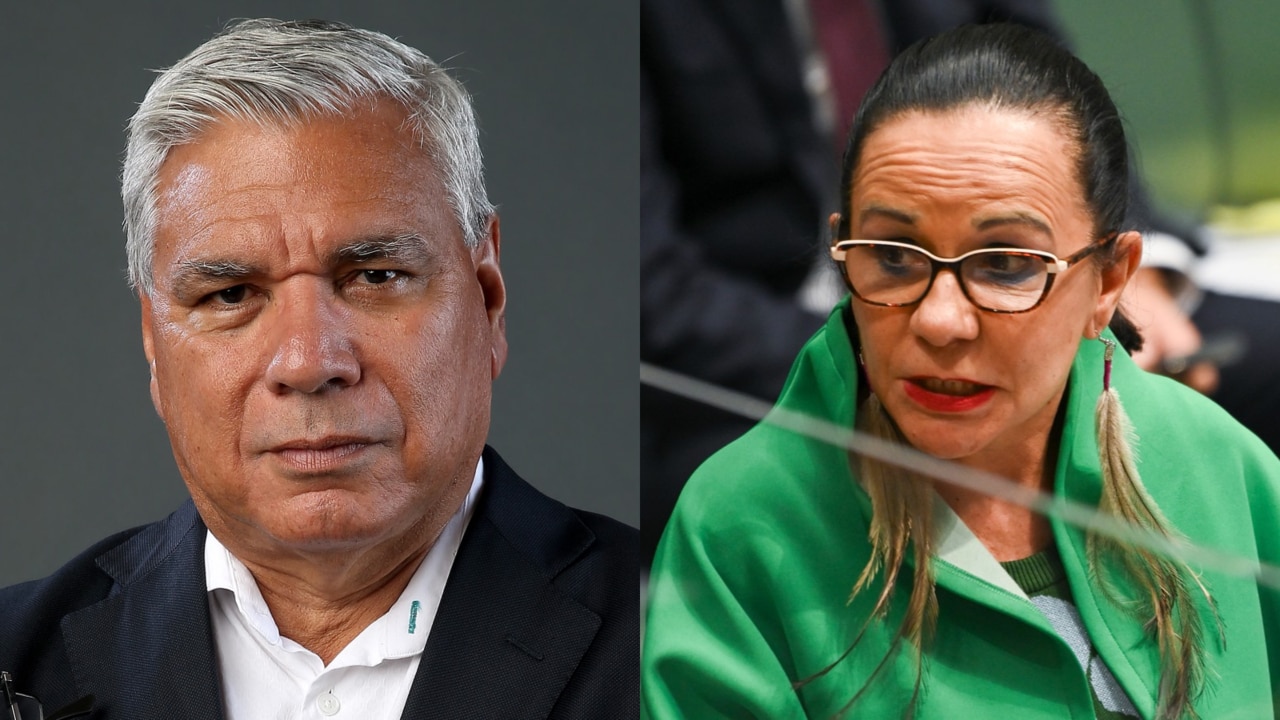

With Nampijinpa Price emerging as the leading national opponent to the Indigenous voice, and me having a long history of voice support and advocacy, the debate has tested our friendship much more than footy rivalry (despite Collingwood’s narrow and controversial recent victories over the Crows). When voice opponents say supporters are creating a racial divide, likening the reform to apartheid, it is difficult for supporters like me not to take this as a personal slight – likewise when voice supporters like me deride opponents as divisive fearmongers, they too, understandably enough, take offence.

I do not want to be too flippant with my footy analogy; obviously the voice debate deals with infinitely more important and substantial differences. But it still provides something of a model, where we might show more respect for our common ground rather than our differences.

The debate will intensify in coming months and it needs to become more civil and rational. There always will be outbreaks of abuse and overreach on either extreme, but the mainstream arguments need to focus on reasonable and factual propositions, accepting that supporters and opponents will mostly all be people of goodwill.

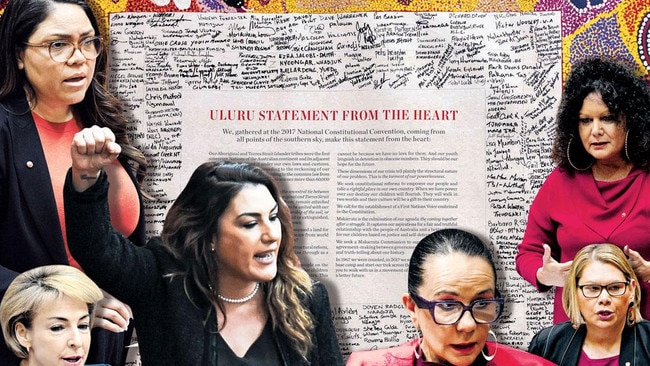

We saw the overreach play out starkly this week when Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney ruined a reasonably effective speech by demonising voice opponents, accusing them of importing Trump-style, divisive politicking from the US.

Not to be outdone, the next day we saw Advance Australia run a No campaign advertisement in The Australian Financial Review that borrowed heavily from the ugly Jim Crow-era racial condescension – Nine Entertainment apologised for publishing the racially charged artwork.

Both sides can and should do better. To be frank, this is more important to those who support the voice than those who oppose it because the uglier and more divisive this debate becomes, the less likely it is that the majority will vote Yes.

Besides, the proponents are the ones advocating change, so the onus is on them to bring people with them. Too often they have done the opposite.

And it has all been so stubbornly predictable. The left-of-centre proponents have ignored the warnings, and pleadings, about how to run the campaign.

In these pages in June last year I warned that Anthony Albanese risked claiming the voice “for the green-left side of politics and thereby diminishing the prospect of bipartisan endorsement”.

Then in January this year I said: “The voice now is often framed as a moral cause (as the left is wont to do) rather than a rational or practical one, so that, in their eyes, robust debate is unnecessary, and opponents can be demonised.”

On air and in print I was not the only one accusing the Prime Minister of expecting “pontification from the elites” to do “the heavy lifting” for the Yes case.

“It is almost as if the institutional left wants to make it as hard as possible for mainstream voters to support this constitutional change,” my column lamented in January. “As the year progresses, and the Albanese government is overwhelmed by other problems, such as the ongoing energy and cost of living crises, it might lose voters’ trust on the voice.”

Tragically for the Yes case, this is exactly how the campaign has played out over the ensuing six months. There has been no obvious attempt to correct the advocacy.

So let me have another go at offering some public advice to Albanese, Burney and the other leading lights of the Yes campaign. They need to campaign in the style of conservatives rather than use the tactics of progressives. After all, they have the support of most on the left; it is the mainstream they must win over.

The modus operandi of the left is to campaign on emotion and demonise opponents as morally inferior or intellectually substandard. The left promotes political fashion and identity issues above practicality and rational arguments.

This is anathema to conservatives and to most people who lean slightly to the right-of-centre, which is where you find most mainstream Australians who tend to cherish values such as choice and personal responsibility. These voters do not want to be lectured or admonished over the voice – they want to know more about how it might work and why it might be important for their country.

The campaign has been devoid of detail, strategy and leadership. So let me offer a five-point plan for how the Yes case needs to turn the campaign around.

And, by the way, this needs to be led by the Prime Minister. No matter how much Albanese wants to portray this as a campaign for others, he leads the government proposing this referendum, he claimed it as a Labor ideal in his victory speech on election night (unwisely in my view) and he must now be at the vanguard of the campaign, despite his many other challenges. So here are my five key points for the Yes camp:

● Campaign like conservatives, not progressives. Avoid the emotive posturing and moralising of the left, and focus instead on the practical and the logical. Respect doubters and opponents rather than demonise them; point out misconceptions or factual errors (such as the nonsense that this would embed race in the Constitution or change the way the whole country is governed), but deal with the erroneous arguments rather than attack the assumed motives of the people making them.

● Establish and repeat the underlying rationale of the voice. This has not been communicated effectively so far. The voice is not an end in itself but a means to an end. Explain how a long process of consultation about reconciliation and recognition decided that the best way to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution is through enshrining a voice that can lead to practical outcomes. This is not a gift to Indigenous Australians but a way to improve the whole nation. Use more non-Indigenous advocates to make these points.

● Emphasise two central facts that put the lie to most of the scare campaigns. The clarity of the constitutional changes, as endorsed by most constitutional experts including two former chief justices of the High Court, confirm that the voice will be advisory only, without any power of veto or direction; and its structure and operations will always be directed and controlled by the parliament.

● Provide more detail. If not a draft bill, outline the structure and operations of the voice as the Albanese government would like to legislate it after a successful referendum. Trust voters to understand this can all be remodelled and refined by parliaments in the future, but share with them an outline of the voice as Labor would like to implement it.

● Expose the fatal flaw of the Coalition case. There is a stark contradiction that undermines Coalition objections to the voice. The Coalition supports a legislated voice and argues that it would be a useful and safe way to foster Indigenous input into the issues that affect Indigenous Australians. Yet the Coalition also argues that exactly the same body legislated under a new constitutional clause would be racially divisive and dangerous. This is illogical. If an Indigenous voice is worthwhile and non-threatening under legislation, then a constitutional clause that merely requires it to exist can only be a good or neutral reform. It cannot fundamentally change the merit of the idea.

This was never going to be an easy reform to deliver. The lack of bipartisan support increases the degree of difficult exponentially.

But the merit of the idea can win out if proponents engage intelligently with the electorate instead of expecting them to go “with the vibe” or follow the lead of the elites.

A handful of the finest people I know are Collingwood supporters – no, seriously. One of them even came to our wedding all those years ago, and it was noted this was the first time any gathering of our clan had included someone with such an odious association. Still, we also had a few monarchists among us that night, and my brother-in-law now seems enamoured with the Magpies too, even though his son was drafted by St Kilda.