Pandemic a poor excuse for delaying integrity commission

The PM promised us a federal anti-vice body, so where is it? It really does seem that this male-dominated government can’t do two things at once.

Scott Morrison claims that he and his government haven’t had the time they need to make it happen, using the floor of parliament to cite the pandemic as the reason. Given that he spent the full previous week in Queensland campaigning for the state LNP ahead of the election due at the end of this month, the hollowness of the excuse was there for all to see.

It has been a frequently used excuse in 2020. The pandemic has meant parliament couldn’t sit, we were told, the virtual world seemingly escaping the PM’s attention. Ironically on Wednesday morning this week he gave a speech about the importance of business embracing the digital world in the wake of COVID-19.

Nearly 12 months ago, federal Attorney-General Christian Porter received an exposure draft on legislation for an integrity commission, but this week he cited the need for extensive consultation before draft legislation could be presented to parliament. Again the pandemic was the excuse. Ain’t the virtual world grand. It really does seem that this male-dominated government can’t do two things at once.

What happens with the integrity commission going forward will be a fascinating case study in just how dominant the Coalition is in the wake of the pandemic. And how strategic it can be at outflanking opponents.

Trust in government has never been higher, benefiting incumbents at state and federal levels. The Labor Party federally is banking on that changing if the Coalition doesn’t move quickly on the integrity commission. Coalition strategists disagree, believing Anthony Albanese is clutching at straws and appears out of touch with the priorities of Australians: jobs and the economy, their material needs.

The scholar Ronald Inglehart identified the concept of “post-material” voting tendencies in his 1977 book The Silent Revolution. Its thesis was that as western societies saw material needs increasingly satisfied, post-material values such as the environment would rise up as important factors in how voters cast their ballots. Since that time, of course, elections have ebbed and flowed based on issues that could reasonably fall into one of these two categories. Depending on everything from conflict to recession to the individual circumstances of particular voting cohorts.

But in the wake of a pandemic that has thrust the world into recession and seen countless jobs lost and debt ballooning, it is hard to see voters putting too much stock in post-material tendencies. Which would mean Labor may be barking up the wrong tree when it comes to the integrity commission, unless it can link that debate to material voting preferences.

A Liberal Party donor receiving a sale price 10 times the value of land he sold to the Commonwealth as part of a purchase surrounding Sydney’s second airport could provide that link. It stinks and it sees political insiders getting rich at a time when mainstream voters are struggling to keep their families financially secure. But the link is still a long bow for Labor to draw, and people need to be paying attention, which they probably aren’t. That said, the issue will likely be in the government’s rear-view mirror as a strategic dilemma before the end of 2020.

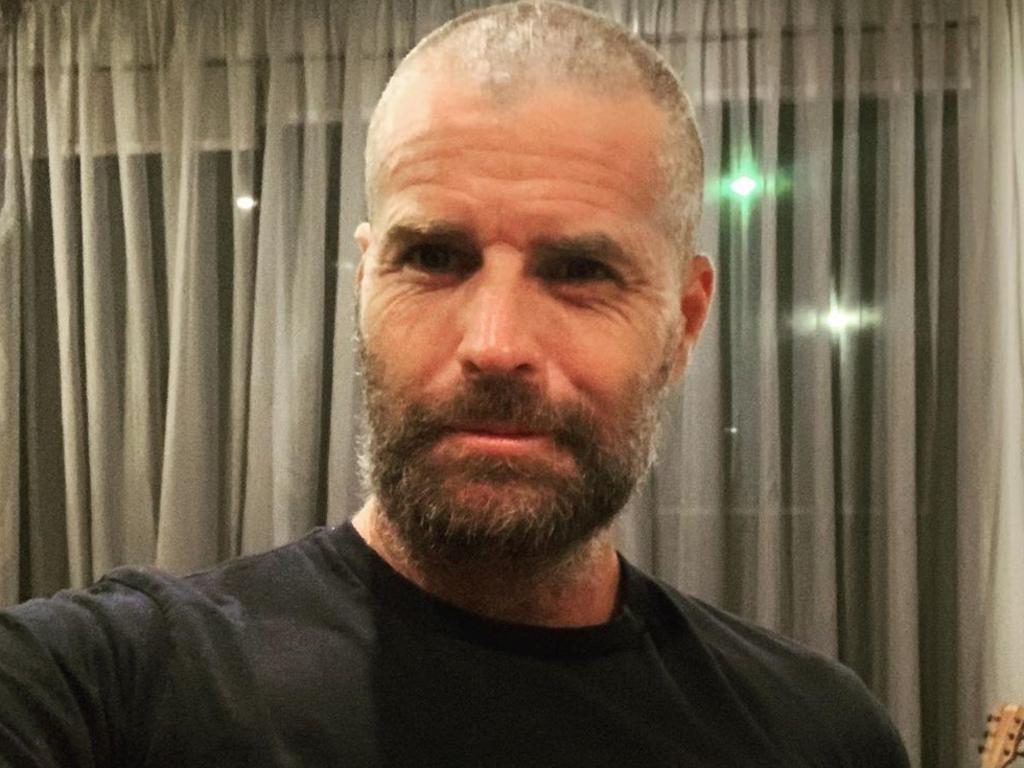

Crossbench MP Helen Haines is tabling a private member’s bill on Monday outlining her own version of a national integrity commission, and she has used the past 12 months to consult widely with parliamentary colleagues on both sides of the major party divide to gauge their support for what she’s proposing.

It is a fair and reasonable compromise between the government’s apparently undercooked options, which would largely see politicians and staffers immune from investigation by such a body, and the more radical models which could see careers ruined on ultimately spurious grounds, as some state anti-corruption bodies have done over the years. This is an important point. At the very least her bill should force the government to harden up its model such that any integrity commission isn’t just a toothless tiger.

The Haines bill will be tabled next week, but it won’t actually be debated before the final sitting week of the year in December.

There are government MPs planning to cross the floor to vote for the Haines bill to be debated, if the government seeks to shut that debate down. And in doing so, there is a good chance that if her bill is opposed by the government they will again cross the floor to see it passed in the House of Representatives.

Remember the Coalition holds only the barest of majorities in the lower house, even if its politically standing because of the COVID crisis is much stronger now. The Haines bill would certainly pass the Senate if the House passed it, because the Senate has already passed a Greens bill for an integrity commission, signalling where the numbers in the upper house rest. It isn’t so clear whether the Senate would pass an unamended government bill for a toothless integrity commission.

But all of the above is theoretical at this stage. The fact Haines is receiving backing from some Coalition backbenchers will hasten Porter and the PM into action with their own bill. To have it ready for tabling in December, before the Haines bill is due for debate. That should be enough to prevent colleagues crossing the floor. And you can bet between now and then the PM’s henchmen in the parliament will be hitting the phones to try to establish who are these rogue MPs willing to cross the floor.

For all the talk in Liberal circles that it’s the party which tolerates conscience votes in violation of party solidarity (when Labor officially bans such practices), if you do cross the floor in the Liberal Party you can usually kiss goodbye to frontbench promotion anytime soon.

The fact some MPs are willing to risk that tells you there are people of integrity in the government’s ranks. Perhaps their voices will grow louder as politics returns to normal and the pandemic fades into the background.

Peter van Onselen is the Political Editor at Network 10 and a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

The return of parliament for the first full week of sittings post the budget saw the Prime Minister batting away questions as to why he still hadn’t established a federal integrity commission. Despite having committed to doing so nearly two years ago, shortly after becoming PM.