American-Australian alliance: Pacific forces reunite

The Battle of the Coral Sea captures the essence of a long alliance.

The recent 80th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea, in the words of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, shone a spotlight on the “unprecedented partnership” between the two countries, one that has survived world wars and a century of joint sacrifice.

On that occasion, it was the naval battle fought by US and Australian forces in the Coral Sea in 1942 that helped turn the tide of the war against Japan. Today, the joint strategic challenge facing both allies in the region is less dramatic but perhaps in the longer term, no less important.

The recent decision of the Solomon Islands to sign a security pact with China, one that could lead to the establishment of a Chinese naval base, is a move that has seized attention in Canberra and Washington. Beijing is engaged in a high-level diplomatic push to forge other bilateral agreements with Pacific island nations in a broadbased geostrategic push to influence the politics, economics and security balance of the South Pacific.

In this contest for influence in the region, geography does not change. The Solomon Islands and the oceans around them are just as strategically important now as they were when Japan was seeking a knockout blow against the US navy in the region in 1942.

No one appreciates the lesson of history repeating itself as much as Blinken, who last year became the first secretary of state to visit Fiji in 36 years, in a bid to help combat China’s efforts to influence the region.

In this environment, it was no surprise that Blinken harnessed the 80th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea to underscore the impact it had upon the war in the Pacific and also the fledgling alliance between the US and Australia.

“Eighty years ago, the United States and Australia formed an unprecedented partnership just months after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the bombings of Darwin and Broome,” Blinken said.

“This partnership has endured and strengthened as our nations have commemorated the 80th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea.”

Blinken described the five-day battle from May 4 to 8, 1942, as a “turning point” in the war in the Pacific.

“The battle paved the way for an alliance that today is a foundational underpinning to the stability of the region and for democracy in the Indo-Pacific,” he said.

“We remain committed to our shared values and a shared vision for the region for the years to come.”

It says much about the importance of the Battle of the Coral Sea that, despite the passing of eight decades, the conflict is still remembered as a pivotal moment in the forging of Australia’s most important alliance.

In 2017, for the 75th anniversary of the battle, the then president Donald Trump met then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull in a gala ceremony aboard the WWII aircraft carrier USS Intrepid in New York in a ceremony to mark the significance of the occasion.

So why does this single naval battle, the first in history in which the opponents never sighted each other, carry such weight today? The story of the Coral Sea endures because it is a potent blend of psychology, strategy, courage and luck.

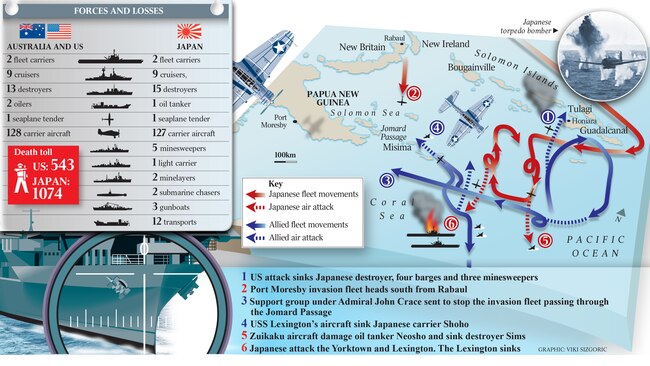

The battle took place following a decision by Japan in early 1942 to send a large invasion force to take Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea and Tulagi in the southeastern Solomon Islands.

From Port Moresby they could have launched regular air raids deeper into Australia and cut vital supply lines. To carry this out, the Japanese launched a flotilla of cruisers, destroyers and transports as well as a half-sized carrier, Shoho, and the aircraft carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku.

But the Allies had partially broken Japanese codes and on April 25, 1942, the Combined Operational Intelligence Centre in Melbourne concluded an invasion of Port Moresby was imminent. In response, the US sent two navy carrier task forces to the Coral Sea, including the carriers Lexington and Yorktown as well as a joint Australian-American cruiser force including HMAS Australia and HMAS Hobart.

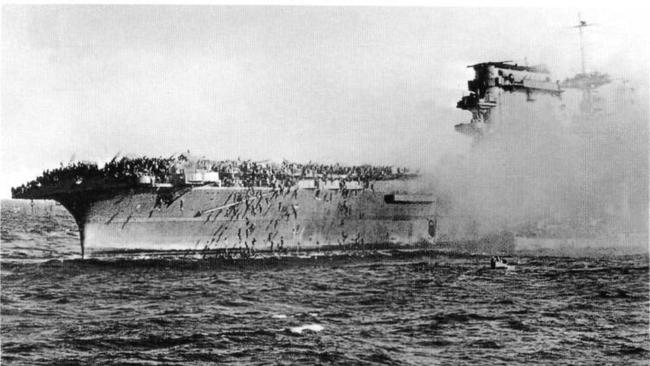

In two fiercely contested days of fighting, which involved aircraft bombing ships, the losses at first appeared to be roughly equal. The US air strikes sank the Shoho and the destroyer Kikuzuki and, heavily damaged the Japanese carrier the Shokaku.

The Japanese also lost 77 planes and 1074 men. The US lost the Lexington, the oiler Neosho and the destroyer Sims, and sustained damage to the Yorktown. It lost 66 planes and 543 men.

But in fact the battle was a devastating strategic defeat for Japan because it forced Tokyo to abandon its invasion of Port Moresby. More importantly, and luckily, the Battle of the Coral Sea meant the damaged Shokaku and its fellow carrier Zuikaku — which did not have enough aircraft after its losses in the battle — were unable to play a role a month later in the Battle of Midway.

Had they done so, the Japanese would have had six carriers to America’s three. Instead, Midway proved to be the decisive battle of the Pacific War, with the US inflicting a devastating defeat from which Japan never recovered.

The Coral Sea was also a major psychological victory for the allies. It was Japan’s first serious setback of the war and it shattered the notion of Japanese invincibility.

For Australia and the US, it showed how the two navies could work effectively together in war.

The late Gordon Johnson, a 19-year-old telegraph operator at the time, told me during the 75th anniversary Coral Sea commemoration in New York that major anniversaries were an important way for younger generations to learn the significance of what unfolded in the Coral Sea.

“I hope it makes people realise how important this battle really was,” Johnson said.

“It was probably more important than Gallipoli because if the Japanese had landed at Port Moresby they would have been on our doorstep. Where we fought was only 880km from Townsville – they really got very close.”

Speaking to the Australian parliament as the Battle of the Coral Sea was raging, the then prime minister John Curtin alluded to the fact that regardless of the result, the conflict would bring the Western allies together in the Pacific.

“I have no information as to how the engagement is developing, but I should like the nation to be assured that there will be, on the part of our forces and the American forces, that devotion to duty which is characteristic of the naval and air forces of the United States of America, Great Britain and the Commonwealth,” Curtin said.

Eighty years on, Australia, the US and Britain are members of a new AUKUS pact to help maintain peace in the region in the face of a rising China.

And once again, the Coral Sea and the Solomon Islands are the hot spots for this new era of strategic rivalry.

Cameron Stewart was the Washington correspondent for The Australian from 2017 to 2021 and New York correspondent from 1996 to 1999.

It is a sign of the enduring strength of the Australia-US alliance – and also of the troubled cycles of history – that after a gap of 80 years both countries are once again joining forces in the South Pacific to defend against a potent strategic rival.