American-Australian alliance: Friends and allies forge future path

Seventy years after the ANZUS Treaty came into force, the US and Australia face a renewed period of uncertainty in the Indo-Pacific.

Beijing’s security agreement with the Solomon Islands, and the extraordinarily aggressive intercept by a Chinese fighter jet of an Australian P-8A maritime surveillance aircraft in the South China Sea on May 26, indicate the shape of the deep troubles that surely lie ahead.

As US congressional mid-term elections loom, as the US defence budget remains relatively stagnant, as Russia’s brutal war against Ukraine grinds on, the bipartisan consensus in Washington remains strong that the Communist Party government in China provides overwhelmingly the greatest challenge, and threat, to the US in the years and decades ahead.

The US remains the world’s largest economy, its most advanced hi-tech centre, with the world’s biggest and most powerful military.

With a population of more than 330 million people, a huge land mass, territories in the Pacific and an unrivalled global network of alliances, the US will remain the world’s leading power as far as the eye can see.

Equally, there is no doubt that China, with 1.4 billion people, the world’s second-largest economy and second most powerful military, is mounting a huge and systematic push to get the US military out of Asia and to become itself the predominant, hegemonic power.

Australia and the US have been formal military allies since Robert Menzies’ great foreign minister, Percy Spender, negotiated the ANZUS Treaty that was signed into being in 1951 and came into force in April 1952. As a result of being part of the British Empire, Australia was allied with the US during World War II, which has allowed Labor sometimes to claim authorship of the alliance. US and Australian troops fought together in World War I as well.

But the US has been central to Australian strategic thinking since the first days of the nation. Australia federated in 1901 as an act of national security. From the start, many of the best Australian minds were fully seized with the idea of promoting a US role in Asian security to the benefit of Australia. After the US-Spanish war of 1898, Washington took control of The Philippines and became an Asian power.

Alfred Deakin, against the wishes of the British, convinced Teddy Roosevelt to send his Great Fleet to Australia as part of its global voyage in 1908. This won overwhelming popularity in Australia, greatly enhanced momentum for the building of an Australian navy and even saw Roosevelt make the first presidential statement committing American effort to Australian security.

So the US has been central to Australian thinking, and planning on security, for as long as Australia has been a nation.

Now Joe Biden in Washington and Anthony Albanese in Canberra need to manage the alliance through its most challenging and uncertain period.

The recently deposed Morrison government deserves credit for Australia’s part in two significant diplomatic advances involving the alliance. One was the elevation of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – involving the US, Japan, India and Australia – to a heads of government level.

The other was the establishment of AUKUS, which groups the US, the UK and Australia for the purpose of greater military technology exchange, and in particular furnishing Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.

The Quad and AUKUS are both important diplomatic initiatives. Yet so far, they exist primarily in the arena of symbolism and signalling, whereas events and confrontations in the Indo-Pacific are so intense now and frequent that it seems that hard power, its reality and the perception of it, will be more important than symbolism.

The elevation of the Quad to leaders’ level was an initiative of the Biden administration and a very good one. Although the Quad is obviously a reaction to Beijing’s regional aggressiveness, it nonetheless tries to have its own positive agenda beyond just security questions. This is a little more doubtful as an effective strategy than it might seem at first.

On the one hand, it is good for the Quad to address the wider region positively and not just in terms of countering China.

It is good for the Quad to combine on certain specific projects, such as providing Covid vaccines, although in fact the Quad was slow in implementation of this.

It’s also good to try to provide the co-ordination of infrastructure financing such that there is an alternative to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

But recent meetings of the Quad have seen it adopt an ever bigger multilateral co-operation agenda that looks like it might become as feckless and unimplementable as all the other acronymic bywords of bureaucratic inactivity that populate the diplomatic world. It should focus mainly on security co-operation.

AUKUS is in some ways more perplexing. Nuclear-powered submarines are more powerful than conventional submarines. They go further, faster, stay underwater longer and carry more weapons. But despite the Morrison government’s confidence that they could be acquired or produced quickly, there is no basis to have any faith in this proposition.

The Royal Australian Navy never brings a new class of naval vessel into service on time. And Australia is starting from scratch in nuclear matters.

If the first boat were to come into service by 2038, which new Defence Minister Richard Marles says is more or less inconceivable, that still means the whole project has to proceed at warp speed through five Australian electoral cycles and four US presidential cycles. And everything has to go just right.

The case for an interim conventional submarine capability is overwhelming, given how badly submarine acquisition has been handled in Australia by both sides of politics since the last Collins-class boat was completed. Peter Dutton’s post-election claim he could have bought two Virginia-class submarines this decade lacks credibility. It contradicts much the former government said previously. If real, and not just magical thinking, it should have been advanced before the election.

Similarly, it’s hard to imagine that AUKUS has produced a revolution in the sharing of military

technology among three allies who were already as intimately allied as it is possible to be.

One big AUKUS announcement was that the US and Australia would collaborate on the development of hypersonic missiles. This announcement sounds impressive until you realise that we have been collaborating intimately with the US on hypersonic missiles for many years. Instead, AUKUS looks to be all about signalling. The US signals its continued commitment and activism in the Indo-Pacific.

The UK gets a validation for its post-Brexit global role. Plus the US and Britain can salivate at the prospect of earning tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars for the sale of submarine technology. And Australia gets to signal that it has big, powerful friends willing to back it diplomatically, politically and with military hardware.

That is all extremely valuable, but it is no substitute for the hard decision to increase defence spending and to prioritise it on weapons and capabilities – missiles, drones, smart sea mines, unmanned ships and underwater vessels and much else – which can be produced or acquired quickly and can make a battlefield difference within the next five years.

So far, the Biden administration has had a strong declaratory and diplomatic position in the Indo-Pacific. And it has broadly maintained defence spending. But the US navy is now smaller than China’s, though still more powerful.

The US is not increasing military spending in a way that lets it build the ships its navy needs, or to transform its military forces into structures that could clearly defeat Beijing’s asymmetric war-fighting strategy.

One weakness the Biden administration has is its lack of a serious trade and economic agenda for the region. Donald Trump is blamed for pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, but it was Barack Obama who declined to even attempt to get the TPP ratified in congress.

The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is anaemic. It is not a trade treaty, so involves no binding commitment from the US, and it does not directly address trade barriers.

However, a deeper question haunts US policy in Asia. The US leadership is certainly convinced of the need to counter Beijing but there is serious isolationist sentiment on the Right and the Left in US politics. Countless memoirs from senior officials in the Trump era reveal how often the former president was on the brink of ripping up US alliance commitments.

He was prevented from doing so by stubborn and responsible officials. If Trump becomes president again, would he display the same instincts? Would he appoint the same officials who constrained him last time?

Meanwhile, Democratic primaries show the party moving ever further leftwards. Biden is almost certainly too old to run for president again. If a younger Democrat president comes from the left of the party, their priority may be overwhelmingly on domestic social spending, not military spending or alliance engagement. And whoever governs the US will be constrained by the staggering debt it is acquiring.

There is a further factor. The first administration of Obama was much better in Asia than was Obama’s second administration. This had multiple causes but one was the presence in the first administration of Kurt Campbell as assistant secretary of state for Asia and the Pacific. Campbell was the intellectual godfather of Obama’s pivot to Asia. He was not there in the second Obama administration and its Asia policy fell away.

Today, Campbell is the highly influential Indo-Pacific Co-ordinator in the Biden administration and has been an engine in Washington’s involvement in AUKUS. Will he serve in the next administration, and if not, will his replacement have anything like his energy and drive?

None of this is to cast doubt on the strength and utility of the US alliance for Australia. The US is the most benign and generous super power the world has known. Its power, and its commitment, are not infinite but the US has been the best ally Australia could possibly imagine.

It is likely that whatever happens, some at least of the Washington leadership would always consider Australia a core US national interest.

Yet given the relative gain in Chinese power, the emergence of Russia as a renewed strategic competitor, Iran edging closer towards a nuclear weapon and North Korea continuing to expand its nuclear arsenal, it could well be that the US is required at some point to deal with multiple security crises simultaneously.

The uncertainty of this strategic environment demands that Australia give life to what was once a governing mantra, achieving defence self-reliance within an alliance framework.

The US alliance is overwhelmingly in Australia’s interests. It also expresses our human and democratic values. It is the coin of much influence that Australia has in Asia, and in the world. For example, Paul Keating often boasts of the influence he had in Asia. His core Asian policy was the promotion of APEC and especially its elevation to a summit. But the simple truth is that it was Bill Clinton who convened APEC at summit level.

Many of Australia’s regional achievements paradoxically involve Canberra convincing Washington to do something. Similarly, our influence in Washington is a substantial part of our consequence in Southeast Asia. It is impossible to know what Beijing has in store for the region. It is clear, not only from the Solomon Islands security agreement but from Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi’s extraordinary eight-nation tour of the South Pacific, that Beijing is working diligently to establish a military base in the South Pacific. This would be a devastating blow to Australian security.

Canberra, Washington and Wellington will work overtime to make sure it doesn’t happen, but there is at least a 50 per cent chance that it will happen anyway, despite our best efforts.

Similarly, there is every chance Beijing will succeed in establishing bases in Southeast Asia, notably in Cambodia.

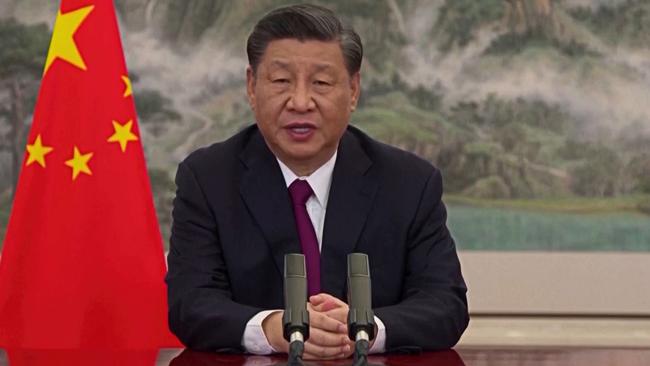

Western analysts are unanimous in their assessment that Xi Jinping wants to take control of Taiwan during his reign in China. Moscow’s setbacks in Ukraine may make Beijing more cautious, or it may result in Beijing designing military action against Taiwan that it can complete much more quickly than Russia’s campaign in Ukraine. These matters are unpredictable. What is clear is that Australia needs to make a much greater effort, over a much shorter timeframe, to get substantial, meaningful, lethal, deployable, offensive and defensive asymmetric defence capabilities as soon as possible.

Given that the decade ahead is perhaps our most dangerous, this is probably more important than nuclear subs a long way over the horizon.

The US alliance has been central to our security for 70 years. The US itself has been a key part of our security for more than 120 years. It is an alliance genuinely based on shared interests but also on deeply shared values. It will likely have a future as important as its past. It will be much better, however, if Australia can contribute much more in its own right militarily.

Australia’s strategic future is now subject to two great and new uncertainties. First, what is the limit of China’s strategic ambition? And second, what is the strength of the US strategic commitment?