Opioids epidemic: the prophets of pain

A family’s reputation is in free-fall as it seeks to fend off claims of responsibility for the US opioid epidemic, which claims 130 lives in the country each day.

The Sackler family epitomised the American dream. In 1952 three brothers, Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond, bought a small company and transformed it into the US pharmaceutical giant Purdue Pharma.

The family became multi-billionaires in the mid-1990s with the advent of the company’s blockbuster drug, the opioid painkiller OxyContin. With a combined wealth of $US13 billion ($18.3bn), the nation’s 19th richest family spread its largesse into philanthropy, becoming a global benefactor of the arts.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a Sackler wing and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington boasts the Arthur Sackler Gallery.

But now the family’s reputation is in free-fall as it seeks to fend off claims the Sacklers played a key role in creating and driving the American opioid epidemic, which claims 130 lives in the country each day.

A civil suit filed in New York accuses eight members of the Sackler family of contributing to the opioid epidemic, with New York State Attorney Letitia James describing the Sacklers as “masterminds” of a scheme that “literally profited off the suffering and death” of Americans.

The Sackler family company, Purdue, now finds itself the subject of lawsuits from 36 states and more than 1500 US cities and counties accusing the company of helping create the opioid crisis.

Big pharma in spotlight

The legal cases, which seek penalties and damages against Purdue, are part of a sweeping attempt in the US to hold the powerful pharmaceutical industry to account for a crisis in which 400,000 Americans have died from overdoses involving prescription or illicit opioids since 1999.

In Minnesota last week, the state Senate voted overwhelmingly to increase fees sharply on makers of addictive prescription drugs to raise $US20 million to combat the opioid epidemic.

Last week Purdue agreed to a $270m settlement with Oklahoma’s Attorney-General in a deal that creates a national addiction centre.

The spate of lawsuits allege that pharmaceutical giants such as Purdue aggressively marketed their drugs while knowing they were dangerously addictive, and deliberately misled doctors who then prescribed them like lollies, creating a generation of opioid addicts.

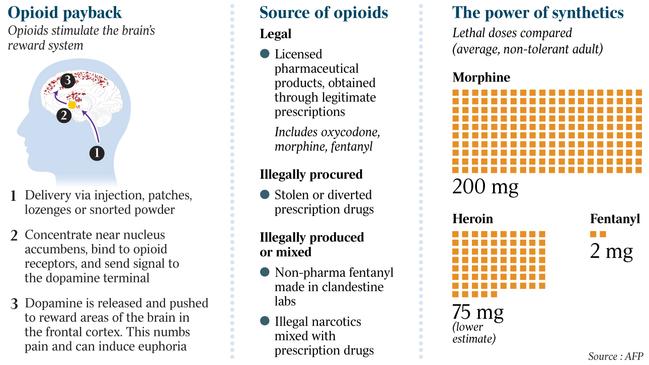

Once the pills ran out, many of these newly minted addicts moved on to other deadly drugs such as black-market heroin and, the deadliest of all, fentanyl.

A 251-page suit filed in New York paints the Sackler family as the human face of a drug industry that chose profits over lives.

The Sacklers deny the allegations, saying they are “a misguided attempt to place blame where it does not belong for a complex public health crisis”.

But the claims against the Sacklers include numerous damning emails from members of the family who still own Purdue through family-controlled trusts.

Project Tango

The suit alleges that not only did the Sacklers help to trigger the opioid crisis through their aggressive marketing on OxyContin but, when they realised their drug was creating a society of addicts, they sought further profits by trying to corner the market for anti-addiction drugs.

A secret project called Project Tango allegedly plotted to capitalise on the sale of the addictive OxyContin as well as new drugs to treat the addictions the company had helped create.

“Pain treatment and addiction are naturally linked,” a Project Tango document states.

The document says the company could make money from both pain treatment and addiction as an “end-to-end pain provider”.

It depicts a blue funnel with the fat end labelled “pain treatment” and the narrow end labelled “opioid addiction treatment”.

The suit states: “The Sacklers’ full understanding of opioids’ abuse and addiction risk is underscored by their willingness to research, quantify and ultimately monetise opioid abuse and addiction by pursuing the development of medications to treat the addiction their own opioids created.”

It cites a Purdue business slide that states of addicts: “It is an attractive market. Large unmet need for vulnerable, undeserved and stigmatised patient population suffering from substance abuse, dependence and addiction.”

The New York suit outlines the extensive efforts of the Sackler family to promote OxyContin from the mid-1990s, even after the family knew of its dangerous addictive qualities.

In 1996, Richard Sackler, vice-president responsible for sales, told a launch party for OxyContin that the drug would create “a blizzard of prescriptions that would bury the competition”.

“The prescription blizzard will be so deep, dense and white,” he said.

A 1998 company promotional video called I Got My Life Back, claimed the rate of addiction for OxyContin was “much less than 1 per cent”.

The lawsuit states: “Even while promoting these misrepresentations, Purdue knew that patients who used opioids prescribed were at risk of developing an addiction.”

Victims blamed

Purdue aggressively marketed its new drug. It held sales conferences around the country, handing out fishing hats, stuffed plush toys, and compact discs with songs with titles such as Get in the Swing With OxyContin to persuade a generation of US doctors that OxyContin was the best painkiller.

It spread the claim that Americans were suffering “an epidemic of untreated pain” and OxyContin was a long-lasting, safe and non-addictive alternative that would revolutionise pain management. Its sales teams monitored doctors and tried to persuade them to prescribe the drug whenever possible.

Sales of OxyContin soared from $US48m in 1996 to $US1.1bn in 2000, but by 2004 it also had become the leading drug of abuse in the US.

In 2001, when reports of overdoses were starting to soar, Richard Sackler adopted a new strategy of blaming the patients.

“We have to hammer the abusers in every way,” he allegedly says in an email.

“They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

Court documents say that when 59 deaths from OxyContin were recorded in a single state in that same month, Sackler wrote to Purdue executives: “This is not too bad. It could have been far worse.”

In 2006 the law briefly caught up with Purdue when it agreed to pay $US600m to resolve claims that it misled consumers.

But the New York lawsuit alleges the family still pushed the marketing of the drug afterwards, with Richard Sackler in 2011 arguing to his own executives that safety warning labels should be removed.

“Richard asserted to the vice-president of sales that a legally required warning about Purdue’s opioids wasn’t needed,” the suit states.

“He asserted that the warning ‘implies a danger of untoward reactions and hazards that simply aren’t there’. Richard insisted there should be ‘less threatening’ ways to describe Purdue’s opioids.”

‘Dispensed like candy’

Purdue’s marketing push for OxyContin was greatly assisted by rogue distributors who bought in bulk from manufacturers and sold them to pharmacies.

These companies, some of which were also named in the New York suit, were legally bound to monitor the quantities sold to each vendor and to alert regulators if the amounts seemed excessive.

But the suit alleges distributors turned “a collective blind eye as orders for opioids in New York skyrocketed”, causing addictive opioids “to be dispensed like candy”.

The Sacklers and Purdue have vigorously defended themselves from blame for America’s greatest public health crisis.

Purdue says the New York lawsuit “irresponsibly and counterproductively casts every prescription of OxyContin as dangerous and illegitimate”, pointing out that the US Food and Drug Administration has approved the drug for patients suffering severe chronic pain.

It claims the lawsuits “ignore the fact that the Sackler family has long been committed to initiatives that prevent abuse and addiction”.

But in the court of public opinion, the Sacklers have become the face of the corporate greed that helped create and fuel an epidemic that has indiscriminately afflicted every strata of US society — from the rich and poor to the old and the young.

Some in America’s philanthropic community are not waiting for the court verdicts to cast their own judgment on the conduct of the family that has bequeathed tens of millions to the arts and other causes.

New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which has been the scene of protests against the Sacklers, says it no longer will accept donations from the family. London’s Tate Gallery and New York’s Columbia University also have banned further contributions from them.

“We are at the point when we as a society need to know the truth about what the Sacklers know,” says Barry Meier, author of Pain Killer: An Empire of Deceit and the Origin of America’s Opioid Epidemic.

“We need to know when we walk past a museum that has the Sackler name on it or a medical school — what did the family know?

“I want to know about the decisions the family made that allowed them to make the money.”

-

Painkillers intensify America’s agony

A visit to the dentist to remove wisdom teeth changed Saige Earley’s life.

She dutifully took the opioids prescribed by her dentist to numb any pain afterwards. But when the pills were finished in 2017, the mother of a two-year-old boy from a small town in New York State was hooked. She moved on to heroin and then to the streets.

“A year later, after committing to recovery, Saige returned home, determined to stay sober and care for her child,” a New York lawsuit against the Sackler family and their company Purdue Pharma states.

“She rekindled her passion for dance, music and art and reconnected with her mother over homemade peanut butter cookies and late-night movies.”

But in September last year, when a friend died from an overdose, she panicked. “I don’t want to die. I don’t want to use. I don’t know how to do this any more,” she told a counsellor. She tried to save herself from relapse. She booked herself into a treatment facility in California and went to nearby Syracuse airport to catch her plane.

They found her body in a cubicle inside the airport terminal with a needle in her arm and her boarding pass in her hand. She was 23.

Personal tragedies such as Earley’s death unfold an astonishing 130 times a day in the US as it fights an opioid epidemic that has become a monstrous public health crisis.

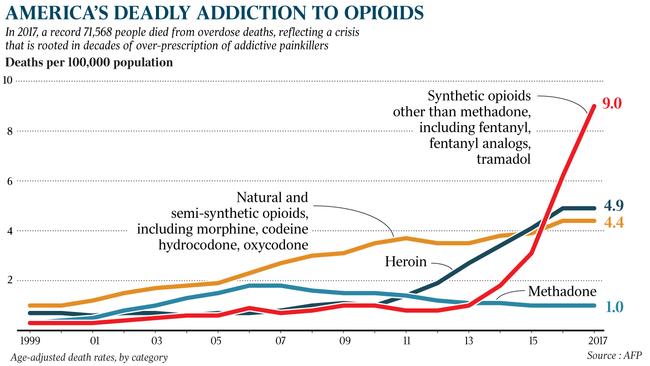

In 2017 a record 72,000 Americans died of a drug overdose, about 50,000 of which were opioid-related. Drugs now kill more people in the country than guns, car crashes or HIV ever have in one year.

Eleven million Americans — the populations of NSW and Queensland combined — are addicted to opioids. For the first time since World War II, the overall life expectancy in the US has fallen because of opioid deaths.

The opioid crisis is indiscriminate in who it targets. Because so many addictions are created by simple prescriptions from the family doctor for ailments ranging from headaches to sport injuries, the drugs afflict everyone — regardless of wealth, ago, race and whether you live in a city of the country.

The opioid epidemic developed in three phases. The first came in the 1990s with new opioid-based pain killers such as OxyContin coming on the market en masse. Around 2010, opioid addicts turned to heroin. The third and current wave began in 2013 as addicts turned to deadly synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2015 236 million prescriptions were written for opioids in the US, or about one bottle for each adult.

The International Narcotics Control Board says the US has 17.4 days of opioid use per person a year compared with only 6.1 days in Australia.

Even so, health authorities will decide within months whether Australia should clamp down on powerful painkillers to avoid a US-style opioid-addiction crisis.

A year after restricting access to codeine, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration is considering its options in relation to stronger drugs such as oxycodone, fentanyl and pethidine. Prescriptions of opioids in Australia are increasing and, according to the latest official data, annual deaths involving opioids nearly doubled to 1119 in the decade to 2016.

Cameron Stewart is also US contributor for Sky News Australia.