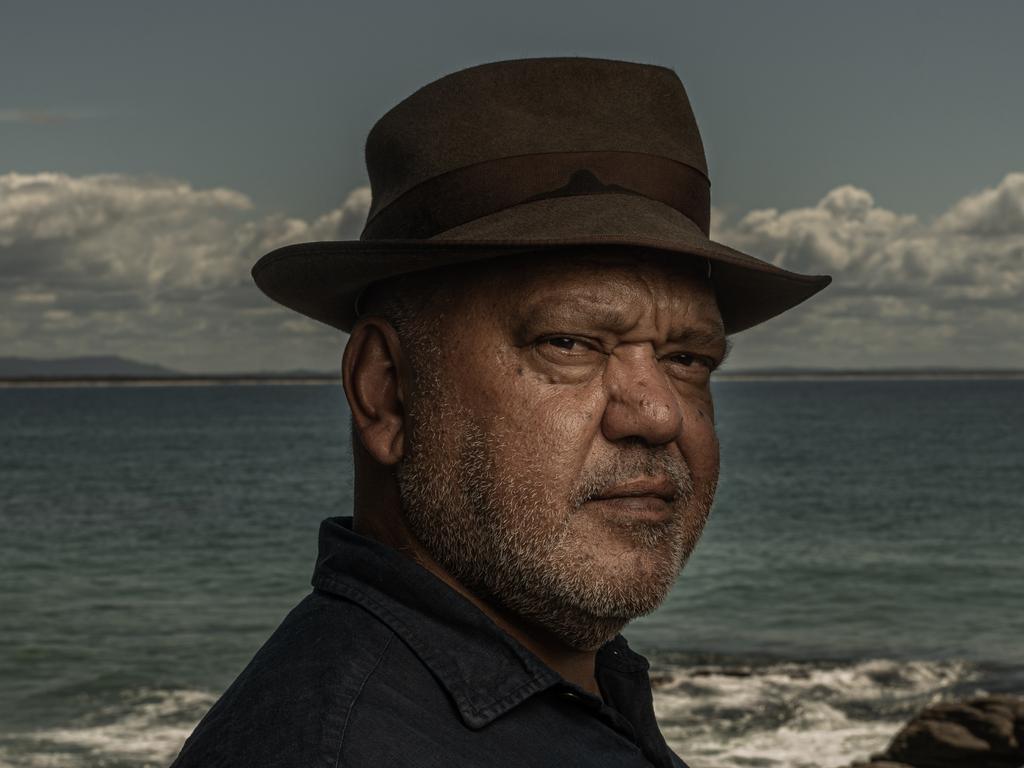

“Biggest pay cheque my father ever got, $45,” he says. “But love, food, blanket, bed, clean clothes, go to school, learn how to read, all of that, I had all of that.”

As he grew up, however, he realised the childhood he “wouldn’t trade for quids” was a world away from the experience of a growing number of Aboriginal children.

“What I increasingly got alarmed about as I grew up was the rising problem of grog amongst young men initially,” he says. “In the ’70s, the grog started to take off with the young men. Why? Free money, welfare, access to the pub, equal rights. It started to snowball with the young men. And then in the ’80s, the young women joining them. And once you get the young women joining them, it gets complicated because there’s children involved, young children.

“And the mother and the father, the grandparents, start to have to look after the young children. And then some of the older men start joining into the drinking and the whole thing snowballed. All of a sudden, some of our young people started ending up in jail. When I was a young boy, there was nobody in jail from my community.”

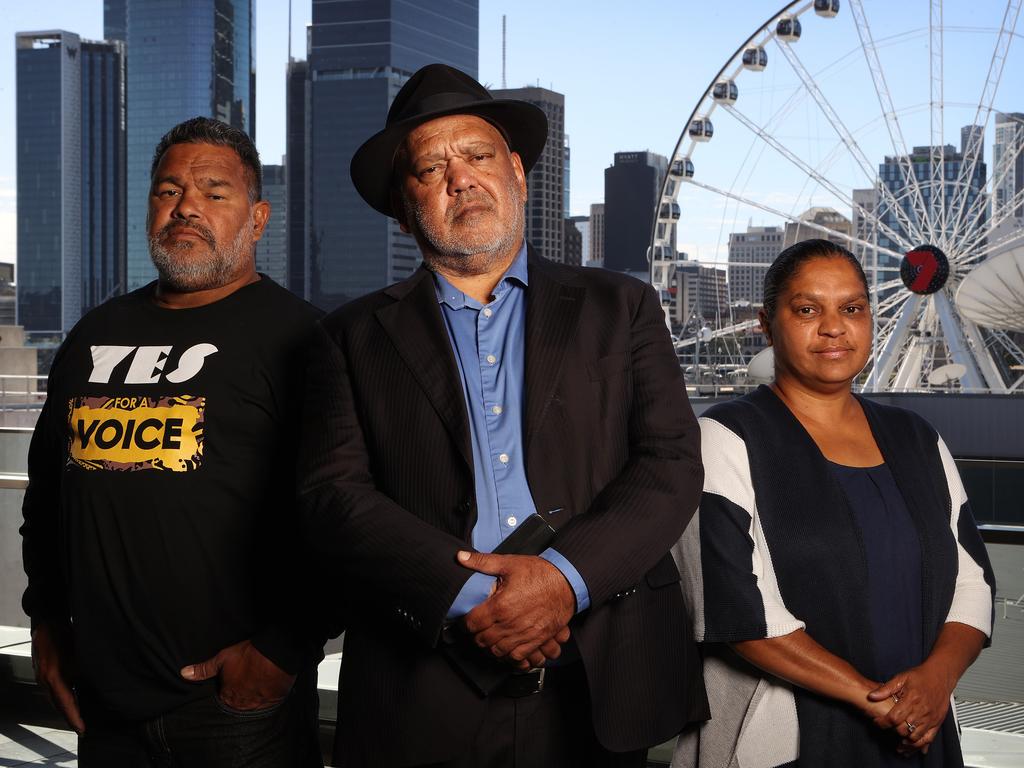

For Pearson, a voice to parliament is all about addressing these issues. Getting Aboriginal people off the grog, getting them working, getting children to school.

He believes the solutions to these issues can come only from people on the ground who understand the issues, not from politicians and bureaucrats who live thousands of kilometres away.

“I want the Cape York people to decide what we do about sending young people off to work,” he says, arguing that the voice should be weighted in favour of remote areas where the issues facing Aboriginal Australians are most acute.

“If the voice referendum is lost, then I’m most fearful about the future of remote communities. I really think this is our last chance to get it right before in the decades to come they become obliterated by the problem.”

Pearson has been at the forefront of the push for constitutional recognition since 2007, when prime minister John Howard first pledged support for a referendum on the issue. Asked why it has taken so long to come to fruition, Pearson replies: “Because it’s a blackfella issue. It’s hard to get a blackfella issue up.”

He is angry at what he sees as a betrayal from conservatives who had supported recognition through four terms of government but never managed to put the issue to the Australian people.

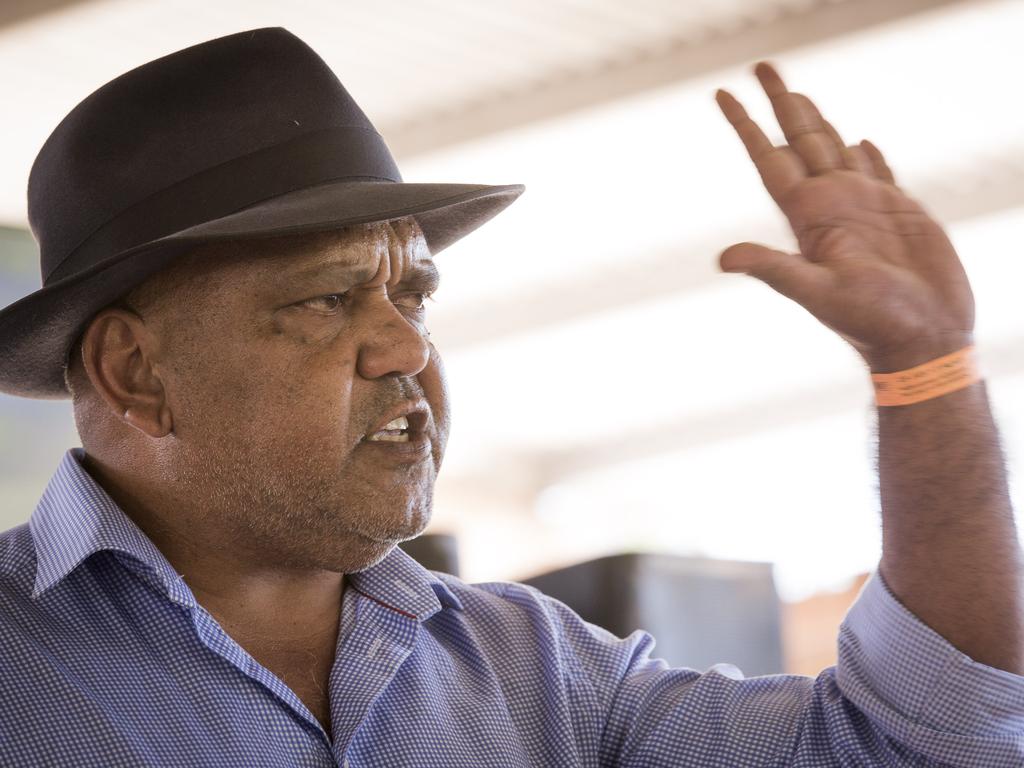

Pearson says he and his supporters have made many compromises along the journey. In fact, he says, the idea for the voice came out of one of those compromises.

The process set up by the Gillard government in 2011 had recommended inserting a non- discrimination clause into the Constitution. It faced fierce opposition from conservatives.

“The conclusion that some of us reached was no, the opposition was implacable and we needed to find a compromise,” he says. “And so rather than a provision that would allow us to go to the court to get the court to rule whether a law was discriminatory or not, we agreed with the idea that, well, why don’t you express your views? Why don’t you be in a position to give advice to the parliament about whether you find a law acceptable or not, what your views are?”

The idea was developed into the voice to parliament, which was adopted as part of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, signed off at the First Nations National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in 2017. But the voice is now the sticking point in a divisive debate some believe could set back to push for constitutional recognition.

Pearson is now at loggerheads with conservatives. But for decades he had won praise from many of the same people for his straight-talking views on Aboriginal affairs.

He has developed and pushed policies praised by conservatives including the direct instruction method in schools and the Cape York Family Responsibilities Commission, which can force parents on to income management if they neglect their children.

Pearson describes welfare as corrosive: “It hollows you, hollows the community out because you’ve got no more purpose any more,” he says. “The purpose of looking after your family and going to work and making sure that the children are the priority, making sure they attend school, all of those things that used to be par for the course when I was growing up, all those things are very hard now. School attendance has collapsed. We fill the jails. The child protection system is bursting at the seams.”

Pearson says he agrees on many issues with Country Liberal Party senator Jacinta Price and Warren Mundine, two leading figures in the No campaign. And he warns that if the voice works properly, some of its recommendations will be difficult for progressives to stomach.

“The progressives are going to have to learn,” he says. “They’re going to have to learn that actual solutions on the ground require a set of policies that Warren Mundine or Jacinta Price would support.”

That includes dismantling a system that has spent billions of dollars trying to address the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, with few tangible outcomes.

“Because what has happened is we’ve built an industry around these poor buggers,” he says.

“We’ve built a massive industry that’s consuming most of the money. A lot of that industry can go and we can turn it into much better things that support families.

“The empowerment of the family, in my view, is where everything ultimately must be focused.”

For Pearson, the voice will mean a brighter future for Aboriginal children: “My parents left me with the best memories, and that’s all I want for the present generation in my community,” he says. “I want them to have good memories about their families and their parents, like I did.”

The Voice: Australia Decides, hosted by Sky News Northern Australia correspondent Matt Cunningham, premieres on Tuesday at 8pm AEST on Sky News.

Noel Pearson’s family was dirt poor when he was growing up on the Cape York Peninsula.