Nineteen years in maximum security: did Kathleen Folbigg do it?

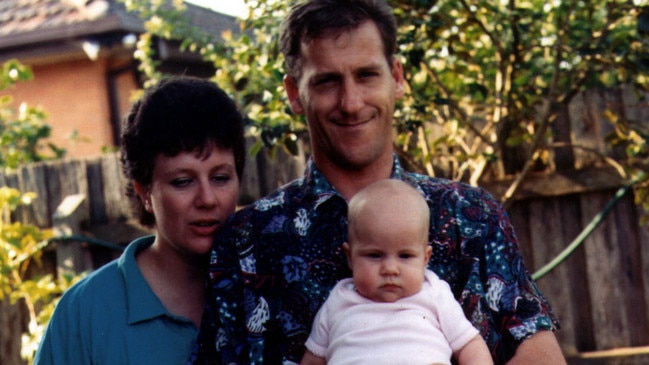

The woman once viewed as Australia’s most notorious child killer, Kathleen Folbigg, has been in jail for nearly two decades. Now the weight of science could free her.

One year ago this week, in a world first, two Nobel prize winners backed a petition to the Governor of NSW calling for the pardon and release of a woman once viewed as Australia’s most notorious “child killer” – Kathleen Folbigg.

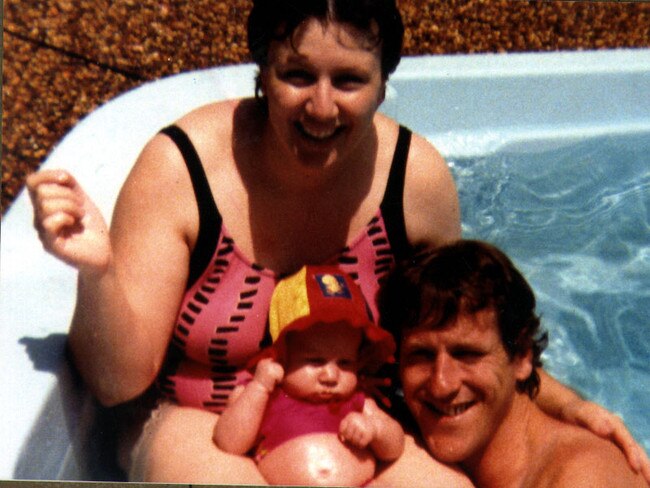

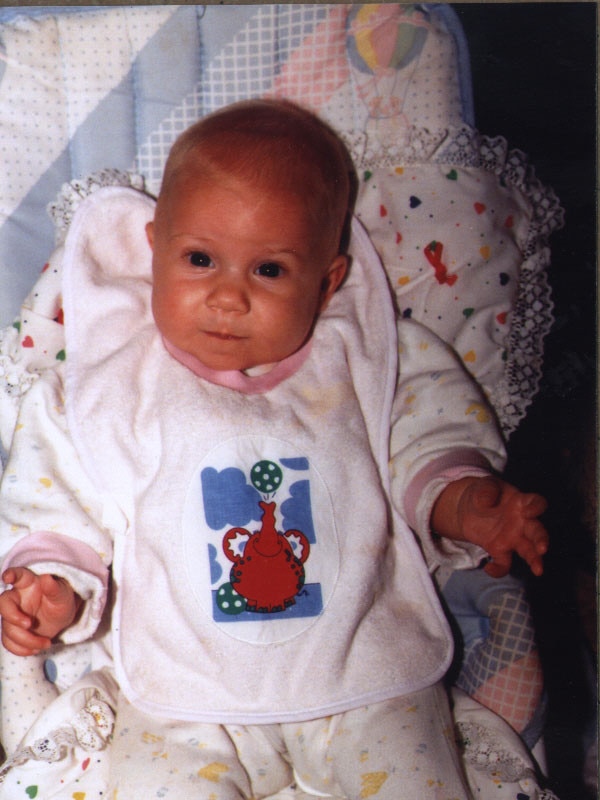

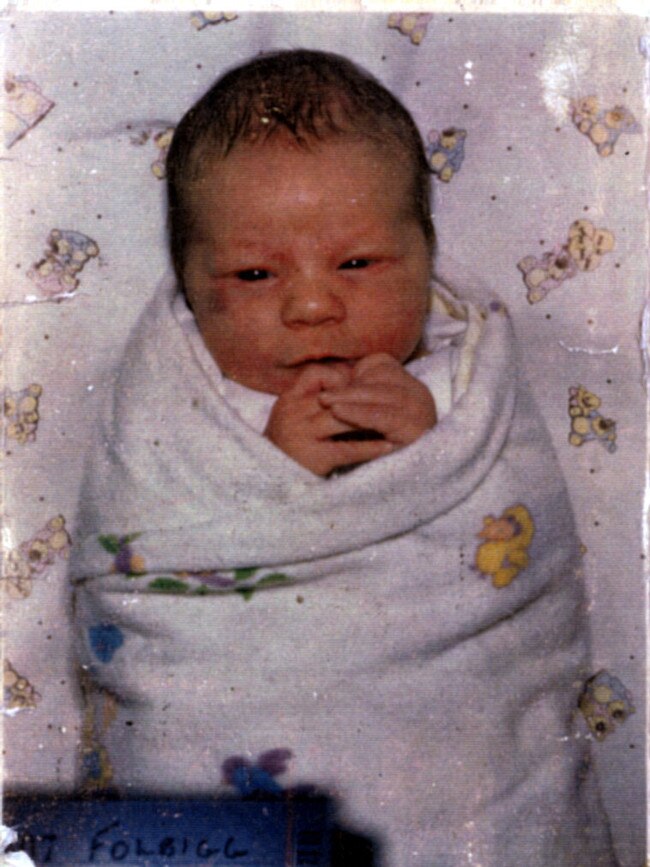

Folbigg was convicted in 2003 of murdering her babies, Patrick and Sarah, and her toddler, Laura, and of the manslaughter of her firstborn, Caleb. Her convictions have been examined in two appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal, one special leave application to the High Court of Australia, and one independent judicial inquiry.

The prosecution’s case, that she had smothered all four of her children, rested on circumstantial evidence, and on the assertion that ambiguous entries she had made in her diaries were “virtual” admissions of guilt. Folbigg has consistently denied harming her children in any way.

Last year’s petition was endorsed by the Australian Academy of Science, and supported by more than 150 scientists, including Nobel laureates professors Elizabeth Blackburn and Peter Doherty. It argued, with the benefit of fresh genetic evidence, that Folbigg “has been wrongfully incarcerated because the justice system has failed her”.

Twelve months on, the petitioners are still awaiting a decision.

The responsibility for that decision lies primarily with NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman, rather than with the Governor, Margaret Beazley. She acts on the advice of Speakman and the NSW parliament’s Executive Council, which is comprised of cabinet ministers who meet in secret.

Speakman, to the dismay of the Australian Academy of Science, has rejected its offer to provide a panel of expert geneticists to work with him in exploring and explaining the fresh evidence highlighted in the petition.

His office has remained tight-lipped, saying only that the petition and its accompanying submissions are “complex and voluminous”, and that a decision will be reached as “promptly” as possible.

‘An innocent woman’

“There has been compelling, fresh evidence for over a year now which supports Ms Folbigg’s innocence,” her lawyers, Rhanee Rego and Dr Robert Cavanagh, told The Weekend Australian.

“The delay is astounding, the process opaque and the lack of willingness to work with scientists, inexplicable. We very much hope the Attorney-General provides his advice to the Governor soon and shows leadership by ending Australia’s worst miscarriage of justice.”

For Blackburn, it is profoundly wrong to deny justice by denying science. “Do those who would deny Kathleen Folbigg’s right to scientific evidence deny that the planet Earth revolves around the sun?” she asks.

Academy president John Shine says: “The petition requesting the NSW Governor release Kathleen Folbigg based on the new evidence has been awaiting advice from the NSW Attorney-General since March 2021.

“Ms Folbigg’s continued incarceration is untenable and it is time that the NSW legal system accepts that a miscarriage of justice has occurred. The power rests with the NSW Attorney-General to not only right this wrong but to bring about the legal reform required so that no person finds themselves in a similar situation.”

On Friday, Speakman’s office insisted that the process of a petitioner applying for the exercise of the royal prerogative of mercy “is not a secretive process”, adding: “The fair and transparent nature of the process is precisely the reason it would be inappropriate and unfair to the petitioner for the Attorney-General to consider material provided by someone other than the petitioner or their legal representative or to hold private consultations with other members of the public. To the extent that the petitioner has sought to rely on any material from the Australian Academy of Science, she has been provided with that material and put forward that which she sought to rely on.”

In a message delivered to The Weekend Australian, Folbigg said: “I am saddened and extremely disappointed that there is no response at the 12-month mark from Mr Speakman in relation to the pardon petition and the overwhelming supporting scientific and medical evidence … I am an innocent woman, and a mother who has lost her family under heartbreaking circumstances, still sitting in a maximum-security prison after nearly 19 long and challenging years.”

NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet has been alerted to the case by Peter Yates, chairman of the Centre for Personalised Immunology at ANU, where much of the work to uncover the fresh genetic evidence was carried out.

“In my discussions with the Premier, I expressed my deep concern about the improper incarceration of Kathleen, and that whilst NSW is a state which supports and creates great science, in Kathleen Folbigg’s case that support for the best science does not seem to have been found in the office of the Attorney-General,” Yates said.

Leon Kempler, chair of Questacon’s advisory council and prominent science advocate, decried the delay, describing it as “an international embarrassment”.

“An innocent woman, Kathleen Folbigg, languishes in jail and the Perrottet government remains indifferent to the cruelty of their inaction,” he said.

British research

Folbigg’s trial in 2003 took place following a series of miscarriages of justice in Britain where evidence had been given – wrongly – arguing that multiple infant deaths in a single family must be homicide, unless proven otherwise. The false assumption was characterised as “Meadow’s Law” after British paediatrician Roy Meadow, who gave evidence in court against some of the accused women that was later discredited.

In subsequent years it would be shown that statistically, multiple infanticides in a single family are as rare – if not more so – than multiple deaths from natural causes – in particular SIDS.

A recent study, conducted through Britain’s Care of Next Infant (CONI) program, examined the clinical case records of infants who died suddenly and unexpectedly over a 15-year period.

A team led by British paediatrician Dr Joanna Garstang concluded: “The SUDI (Sudden Unexpected Death in Infants) rate for siblings is 10 times higher than the current UK SUDI rate. Homicide presenting as recurrent SUDI is very rare.”

In one family where the deliberate smothering of three infants by a parent was suspected, the authors wrote: “All three had marked pulmonary haemorrhage on post-mortem examination … There were longstanding child protection concerns with this family.”

No signs of smothering were detected in any of the Folbigg infants. Nor was Folbigg subject to any child protection concerns over the 10-year period from 1989-99, when her children died, one after another.

Folbigg’s legal team argues: “Speculation about the rarity of four deaths in the one family from natural causes led to a default conclusion of murder in the Folbigg case.”

The fresh genetic evidence, the team argues, painstakingly analysed over the past two years, points to the conclusion that she can no longer plausibly be considered to be guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

Diary ‘discredited’

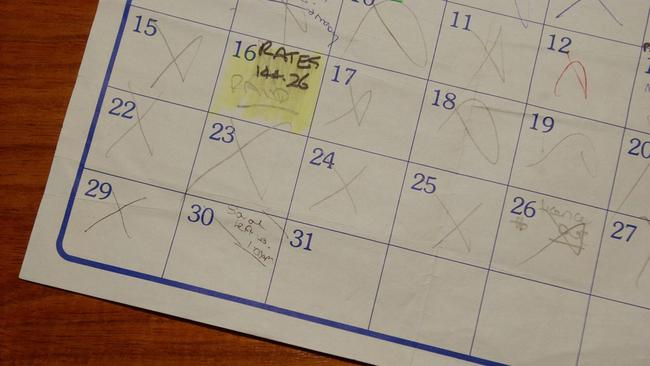

Folbigg’s legal team is adamant the diary evidence that played such a significant role in her convictions is also now completely discredited.

Six separate experts working pro bono have recently written reports disputing the allegation that Folbigg’s diaries contained “virtual” confessions of killing her children.

The latest expert to do so, clinical and forensic psychologist Dr Katie Seidler, has worked with violent offenders in NSW prisons for over two decades.

She says: “There are no clear disclosures of any criminal or violent conduct in Ms. Folbigg’s writings.”

Repeated delays

This isn’t the first time a petition lodged on Folbigg’s behalf has encountered a delay.

Speakman and his predecessor, Gabrielle Upton, took three years to decide on a previous petition lodged in 2015. In 2018, Nicholas Cowdery QC, who was NSW DPP when Folbigg was charged and convicted, described the time it had taken as “an inordinate delay in dealing with the matter”.

Attached to that petition was a comprehensive re-examination of the children’s deaths by world-renowned forensic pathologist Professor Stephen Cordner, who concluded that: “Ultimately, and simply, there is no forensic pathology support for the contention that any or all of these children have been killed, let alone smothered.”

In August 2018, Speakman announced at last that an inquiry would be held into Folbigg’s convictions.

Professor Carola Vinuesa – currently a Royal Society Wolfson Fellow at the Francis Crick Institute in London – told the inquiry that, following the genetic sequencing of decades-old samples, it had been discovered that Folbigg’s two daughters, Sarah and Laura, carried a novel cardiac genetic mutation known as CALM2 G114R, which could have been fatal.

But the inquiry’s commissioner, former NSW District Court chief judge Reginald Blanch refused a request from Professor Peter Schwartz, a world expert in the genetics of cardiac arrhythmias, to examine this evidence further, concluding instead that overall, the evidence he had heard “reinforces” Folbigg’s guilt.

Cause of death

In 2020, Danish scientists carried out experiments on CALM2 G114R, which demonstrated that the mutation was pathogenic.

The resulting peer-reviewed article in the prestigious Oxford journal Europace, authored by 27 scientists from around the world, concluded that the CALM2 G114R mutation was the likely cause of death for Folbigg’s two daughters.

Vinuesa goes further, asserting that, based on established guidelines, there is a “greater than 99 per cent certainty” that the mutation was responsible for the deaths of Sarah and Laura.

New appeal for inquest

This week, tiring of the delay in a decision on last year’s petition, Folbigg’s legal team asked NSW State Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan to hold a coronial inquest into the deaths of all four children.

The team says: “The new compelling genetic evidence indicates the official causes of death recorded for Sarah and Laura are now outdated, and an official finding is required so that the death certificates can properly reflect how they died. In Ms Folbigg’s case, the fresh scientific and medical evidence needs appropriate consideration.

“It is, therefore, in the interest of the administration of justice that an inquest be held into the children’s deaths to determine finally how the children died.”

Solicitor Rego and barrister Cavanagh, who together wrote the submission to the coroner, told The Weekend Australian: “Ms Folbigg has always maintained her innocence. She strongly asserts that she did not smother her children, and now science and medicine have provided explanations for all four children’s deaths.

“Ms Folbigg is asking the state coroner to look at the science and medicine, and to make the findings that her children died of natural causes.”

The Attorney-General’s office defended the time taken to consider the petition. In response to detailed questions from The Weekend Australian, Speakman office said in a statement that since the Attorney-General received the originating petition in March 2021, Folbigg’s advisers “continued to provide additional material over the next nine months”.

“The Attorney-General has therefore been in possession of all the material on which the petitioner presently relies for under three months. Suggestions that the Attorney-General has been in possession of a complete petition for any longer are inaccurate.

“The material provided as part of the petition consists of approximately 5100 pages and consideration of that material and the updated grounds is a process that must be taken with great care and diligence; as is the case with all petitions. As such, the Attorney-General has instructed the Crown Solicitor’s Office to obtain the advice of senior and junior counsel on the matters raised in the petition.”

Review commission

Folbigg’s case has highlighted the growing support in many countries for criminal case review commissions that work independently, with substantial powers to investigate alleged miscarriages of justice.

Dr Robert Moles, Associate Professor at Flinders University, says: “In the UK, referrals from a CCRC, which was set up in 1997, have to date overturned more than 100 murder convictions, including the historical convictions of four people who had been hanged.”

Similar CCRCs have been set up in Scotland, Norway and, more recently, New Zealand. Canada too will now set up a Miscarriages of Justice Commission.

But none, so far, has been set up in Australia.

Cowdery says there is a lot of support for the establishment of a CCRC.

“I think it’s an idea worth exploring. It’s working very well in the UK and in Scotland. and New Zealand has a similar body. It is planned for Canada. We should give serious consideration to setting up one here,” he says.

Meanwhile, Folbigg waits. Her legal team has recruited legal heavyweight David Bennett QC, a former commonwealth solicitor-general, to help take her case forward. Currently in her 19th year behind bars, Folbigg will be eligible for parole in six years.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout