In 2023, war photojournalist Andrew Quilty travelled with his cousin Simon Quilty to Tennant Creek to document the effects of climate change and poorly designed “hot box” homes on residents. Some of the Indigenous housing conditions the pair witnessed there shocked Andrew Quilty, who had spent years capturing the devastation of war in Afghanistan. In a cover story for The Weekend Australian Magazine, the nine-time Walkley award-winner wrote: “The living conditions for (Aboriginal) people in and around the town are, in many cases, worse than in some of the poorest communities in Afghanistan.” At Drive-In Camp 2km east of Tennant Creek – named for a shutdown drive-in cinema – Andrew Quilty photographed Dalabon-Kaytetye man Mr Camfoo, who had spent years living in a tin shed with a dirt floor and without running water, reliable power or windows. His bed was a crumbling foam mattress propped up on milk crates. Andrew Quilty’s unsettling portrait captured the depth of the elder’s poverty and of the Northern Territory’s housing crisis. Drive-In Camp’s sheds had been declared uninhabitable by the Howard government in 2007, but Aboriginal people continued to live there because of the acute housing shortage. Mr Camfoo was befriended by Simon Quilty, a doctor who worked in the NT for 15 years and campaigns for better housing and energy security for Indigenous people. The Indigenous elder died recently, and here SIMON QUILTY pays tribute to a “true bushman”, father and grandfather who “never held a grudge” despite waiting more than 20 years for the “proper house” he was ultimately denied.

I pulled up into his camp last week, the air full of heat and moisture with solid white clouds gently turning orange in the afternoon, building up to look like rain was coming.

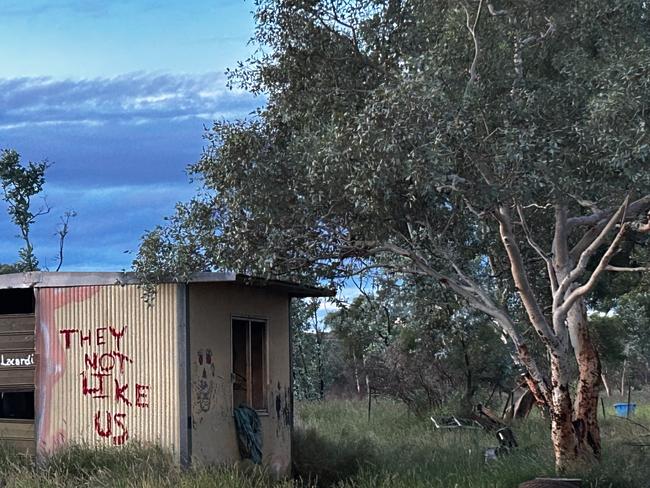

Mr Camfoo’s tin shed looked busier than usual, a group of boys wandering through the surrounding sand playing with sticks, an old Holden covered in red dust pulled up out the front, and striking new graffiti on one of the external walls, newly painted in red capital letters, “They not like us”. Two crystal clear and parallel meanings. Of course “they” are not like “us”, I thought. As if my family could survive such hostile conditions. And the way Mr Camfoo and his family have been forced to live, it can only be presumed that someone in control doesn’t like who he, or “us”, is.

His daughter, in her early 30s, came to my car window. He’s moved over that way, she said, pointing towards Peko Mine hill. A few hundred metres away I could see some kind of dwelling near two gum trees. I followed the tracks through the spinifex and there he was, sitting on his bedframe that he’d dragged out into the open. At first he didn’t recognise me in the work ute, but when I stepped out he smiled at me, hello my friend.

Mr Camfoo had been living in a tin shed, no insulation, no power, no water, dirt for the floor, for much longer than the five years I had known him. He was always my second or third stop to visit when I pulled into town, to say hello and have a cup of tea and talk about what was going on around town. He wasn’t good at numbers, but for more than 20 years he reckoned he’d been waiting for a proper house, something he’d never experienced. He didn’t mind though, he loved the bush, and he knew how to quietly wait.

He grew up in Arnhem Land in the 1960s. Rembarrnga and Dalabon people were treated with extreme brutality right up until the 1930s and beyond, and so I expect his parents would have suffered violence in a way now hard to imagine on Australian soil.

He’d married up to a Warumungu woman and moved to Tennant Creek in the 1980s, and there he’d stayed, his family moving into this tin shed in Drive-In Camp 2km east of town. Up until 2007 at least they had water, but when the government took over housing the shed was deemed uninhabitable and so, to move the occupants on, the water tank was removed. They had no choice but to stay in that little shed on the outskirts, hidden in the scrub.

When he needed water, if he had a car he’d fill the boot up with 20L plastic drums, and when there was no car he’d borrow his daughter’s pram and wheel the drums over to the Peko Mine tourism site where there was a tap.

Once when I visited he’d borrowed a small and well-used generator and a TV to watch the footy finals live from the MCG, but the only other power he’d regularly use was from faded and weather-beaten solar lights.

He’d told me he hoped to one day live in a house with power and water, but Mr Camfoo never was in a rush and never complained. As a Dalabon-Kaytetye man, an outsider on Warumungu country, he accepted that there were many other families from this country who deserved a house before him.

And so he patiently waited. The cold weather was OK, he reckoned, just light a fire, pull his bed out under the stars in the winter, it was all right. Summers were pretty brutal, though, when the sun beat down and the mercury hovered above 40C for day after week after month. The radiated heat under the tin roof was overwhelming at times but that was OK, he’d just set up a chair under a tree with a bucket of water and wait for the cool southeasterly breeze that heralded the dry season.

He would sit there and take note of everything: the family of peewees nesting each year, the honeyeaters, the flowering of the arid bush when it rained, the steadfast green of the snappy gums that succumbed only to the hottest years. And never would he complain. He had not lost his culture, and he was surrounded by country that, although he was a visitor on, he nevertheless loved as Mother Earth and had everything that he needed. He was a true bushman, like many of the old people who live in Tennant Creek, and he was my friend, a person who reminded me every time we sat together of the value of joy despite hardship.

I’d seen him only a few months earlier, still living in that old tin shed, but that night, as I was sitting close to him on his mattress, he told me his daughter had recently become homeless and so he moved out to make way for her children to have somewhere safer to stay.

There was an old busted caravan that had a makeshift corrugated iron awning once built for shade that had been abandoned years ago, and so he moved his mattress and his life to make way for his grandchildren. Purposeful downsizing, Tennant Creek-style. Of course he did, they were his grandchildren. As we sat there chatting, one of them rode past on an old BMX, smiling at his grandfather as he left snakelike prints in his speedy wake.

I left him as the dark arrived, see you tomorrow old man, I’ll bring you a coffee. He smiled at me, bo bo, he said, goodbye.

That night as I slept, the clouds turned to storm and in the early morning hours I was woken by a bang of thunder that shook me awake, the rain smashing down on my roof and bringing that magnificent smell of a desert coming to life, and I hoped he was not getting wet – that old caravan didn’t have any windows.

When I pulled in through the puddles the next day as I’d promised, he wasn’t there. His daughter and son came walking towards me from their tin shed looking distressed. He’s gone, they said, as I stepped out of the car. He’s gone. Last night, that old man, he finished up.

Mr Camfoo never held a grudge that his father and grandfather had their land taken from them with no exchange for a better life. He never complained about the predicaments he faced because he was not allowed to go to school and could not read or write, could not fill in Centrelink forms, didn’t understand this money business or the way non-Indigenous people accumulate material wealth by using knowledge that belonged to their ancestors and not his. He didn’t blame anyone. He didn’t have a problem with white people, never said a bad word of anybody, no government department or official, no driver of inequity.

He did, however, want a better life where his family would be given opportunities to shape their future and reliably feed and shower their children and keep them safe from the increasingly extreme summer heat, but I am pretty sure he knew this was unlikely, and he just accepted the way things are in Australia.

Rest under the stars in peace, Mr Camfoo. Your generosity of spirit, your kindness, your lack of anger and resentment to the way you were forced to live, your love for your family, your extraordinary resilience, were deeply inspirational to the many people who knew and loved you.

Mr Camfoo died on April 2. He leaves behind his old partner, six children and 13 grandchildren.

Simon Quilty is a doctor who has worked throughout remote Northern Territory for the past 15 years. He is now working with the housing organisation Wilya Janta (wilyajanta.org) and Warumungu people to design homes that are culturally and thermally appropriate for northern Australia.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout