Images by Andrew Quilty

The words “Jesus Christ” and an image of the crucifixion are painted on a rusty metal shutter that serves as a window in Steven Camfoo’s tin shed home. This simple yet cleanly-executed painting depicts the three crosses at Calvary, with emphatic pairs of quotation marks highlighting Jesus’s cross.

It’s an unselfconscious declaration of Christian faith, and it stands in almost shocking contrast to the despair that seems to engulf Camfoo’s home in Tennant Creek, which is captured in a powerful photographic series by internationally celebrated photo-journalist Andrew Quilty. From the dirt floor to the crumbling foam mattress and bed supported by milk crates, to the torn bedspread stretched across a corrugated tin wall – a forlorn attempt at home decoration – Quilty’s photos underline the severity of the remote Indigenous housing crisis.

In 2022, the photojournalist returned to Australia after a nine-year stint in Afghanistan, where he covered the devastating impact of decades of war on the Afghan people. His images – including a portrait of seven schoolchildren from the same family who all lost limbs when a grenade exploded – could hardly be more moving or confronting.

Indeed, Quilty’s images have been published and acclaimed across the globe; he has garnered a Sony World Photography award, a World Press Photo prize and nine Walkley awards including the highest honour in Australian journalism, the Gold Walkley.

His 2022 book, August in Kabul, was a first-hand account of America’s final, inglorious days in Afghanistan.

Yet he was “shocked” by what he saw in Tennant Creek during a recent photographic assignment on the effects of climate change – from ruinous floods to enervating heatwaves – on ordinary Australians, and how local communities are devising solutions to deal with this. He writes: “The living conditions for (Aboriginal) people in and around the town are, in many cases, worse than in some of the poorest communities in Afghanistan; even in temporary camps for those displaced by the war. The combination of increasingly hot summers due to global warming and poorly-designed homes means that some areas in Central Australia are becoming unlivable.’’

Rural and remote Indigenous housing has long been an intractable problem for federal, state and territory governments: in 1987, the inaugural president of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Justice Marcus Einfeld, famously wept during an inquiry into racial unrest and appalling living conditions – including dilapidated housing, water rationing and leaking sewage – at Toomelah, a small Aboriginal community in northern NSW. (Einfeld was later sentenced to two years’ jail for perverting the course of justice over a speeding ticket, but Toomelah locals remained grateful for his advocacy.)

But as Quilty notes, Tennant Creek’s housing crisis isn’t just about a shortage of dwellings so acute it forces elders like 58-year-old Camfoo to live in sheds. As the changing climate produces longer droughts and record streaks of heat – 2019 saw the highest average daytime temperatures yet recorded across the Northern Territory, according to the Bureau of Meteorology – experts say remote Indigenous homes are being turned into “hot boxes” that endanger the health and inflate the power bills of sick and impoverished residents.

Quilty covered the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires and “jumped at the chance” to do a photo series for the Climate Council on solutions to climate change driven by heavily impacted communities in northern NSW, Far North Queensland and the Northern Territory. He travelled to Tennant Creek with his cousin, Simon Quilty, who worked as a doctor in the Territory for 15 years and says the Indigenous housing shortage, “grossly inadequate’’ dwellings and rising temperatures are exacerbating illnesses including rheumatic heart disease, kidney disease and Covid.

Simon Quilty says that in late 2021, Covid “roared through these communities because people were sheltering indoors in extremely hot weather’’, sometimes moving into neighbouring houses with airconditioning. The specialist physician, who has worked at Katherine Hospital, says that on 45-degree days, “there’s a point where it gets so hot (inside remote Indigenous houses in the Territory), it’s incompatible with life. The residents have to leave, and then they move into another house that becomes even more ferociously overcrowded.’’ Such overcrowding, he says, often leads to social conflict.

Andrew Quilty discovered that Camfoo’s home is in “Drive-in Camp, named after the long-since shuttered drive-in cinema nearby in Tennant Creek. Camfoo has lived here for around 10 years because, he says, he would have to wait five to six years for (housing) availability in Tennant Creek.” There is no rubbish collection, electricity or running water, so “Camfoo collects water in plastic containers pushed in a baby’s stroller’’ – the stroller also features in Quilty’s unsettling visual essay.

Simon Quilty, the brother of Archibald-Prize winning artist Ben Quilty, knows Camfoo and says “he is a dignified man who never complains’’. The physician, who now practises in northern NSW and is campaigning for better housing and energy security – including solar panels – for Indigenous residents, says there are “still probably 20 or 30 tin shed houses in Tennant Creek” and some in Katherine.

He says Tennant Creek’s tin homes were “rightly condemned” during the Howard Government’s 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response Intervention. Services were cut off and a water tank was removed. “But people had nowhere else to go so they stayed,’’ he says. “They put their name on a (housing) waitlist and they are still on a waitlist.’’

Like Camfoo, Warumungu traditional land owner Norman Frank Jupurrurla once lived in a tin shed home without running water or a toilet in the remote settlement of Utopia, 230km northeast of Alice Springs. The former community ambulance driver now lives in a Besser block family home with his wife, Serena, an Alyawarre woman, and their two youngest children at Tennant Creek.

While this house is obviously superior to his tin shed home, Jupurrurla, who has kidney disease and undergoes 15 hours of dialysis every week, says that during recent summers, it was unbearable inside his house when the power was periodically disconnected and the airconditioning stopped working. “I normally just sat under the sprinkler or with the hose over my head,’’ he says, adding that “after six or seven really hot days, when you go to turn the shower on, it (the cold water) is boiling hot’’.

Now, the 50-year-old community leader has joined forces with Simon Quilty, Melbourne design firm Office, Darwin architects Troppo and the Indigenous-run Julalikari Council Aboriginal Corporation to develop climate-friendly and culturally sympathetic houses on his ancestral land outside the Tennant Creek township. This modest yet radical venture is called the Wilya Janta Housing Collaboration and Jupurrurla explains with an air of quiet authority: “Wilya Janta means in my language Warumungu, standing strong, that’s how you want your house to be. Our housing structure, we should be working along with the architects to live in a way we want to live, in a culturally appropriate way. We want to live in a house that can stand for this climate.’’

From tin shed dweller to climate pioneer. In late 2021, Norman Frank Jupurrurla became the first public housing tenant in the Northern Territory to have solar panels installed on his roof and the effects of this have been transformative – for his wallet, anxiety levels and health.

About 10,000 mostly Indigenous public housing tenants in the Territory use a pre-paid system for their electricity. The scheme prevents residents from running up unsustainable power bills: if their credit runs out, their power is disconnected until their meter is topped up again. However, a spike in temperatures and energy use leads to frequent and lengthy disconnections. In the 12 months before solar panels were put on Jupurrurla’s roof, he was disconnected from his pre-paid meter 12 times. After the panels were installed, there were no disconnections.

“Without panels on the roof, I suffered. I had to look around for money nearly every second day to put power in, but today it’s like it’s nothing,’’ says the Julalikari Council board member.

Before the father and grandfather had his panels installed, it was deemed technically impossible to connect Territory pre-paid power users to solar panels: Jupurrurla’s breakthrough followed years of negotiations with private companies and bureaucrats. “Keep on shaking the bush,” is his mantra, “or nobody will listen to you.’’

According to one disturbing study by Jupurrurla, Simon Quilty and Alice Springs’s Tangentyere Council, from 2018 to 2019, the average remote Indigenous household was disconnected from power 10 times a year for up to 10 hours at a time. When this happens, perishable food in refrigerators can rot and potential lifesaving drugs – including insulin – can be denatured, while oxygen concentrators break down, says Simon Quilty.

He says: “With this energy insecurity the solution for a lot of people is to just not own a fridge. Poverty means that often, it comes down to a choice between power and food. It’s surprising how often in really hot weather, people choose power over food.’’

He concedes that in recent years, the Territory government has built houses with improved insulation. However, he claims “houses like Norm’s have incredibly poor thermal design and construction’’ – the eastern-facing wall has no eaves – which increases internal heat and power bills. “If you don’t aircondition on a 45C-degree day, the inside of the house goes well above 50C degrees – and many people think he’s got a good house. Power bills (for homes without solar panels) are extreme. … It doesn’t have to be this way. You could have houses that were appropriate for the climate and the culture.’’

Between December 2018 and January 2019 Tennant Creek experienced 23 consecutive days of temperatures above 40C degrees, breaking the previous record set in 1938, according to the Bureau of Meteorology. While there was recent flooding in the Territory and 2021 and 2022 brought above-average rainfall, in 2021 parts of the Barkly district that takes in Tennant Creek “had daytime temperatures in their highest 10 per cent of long-term records’’, BOM reports show.

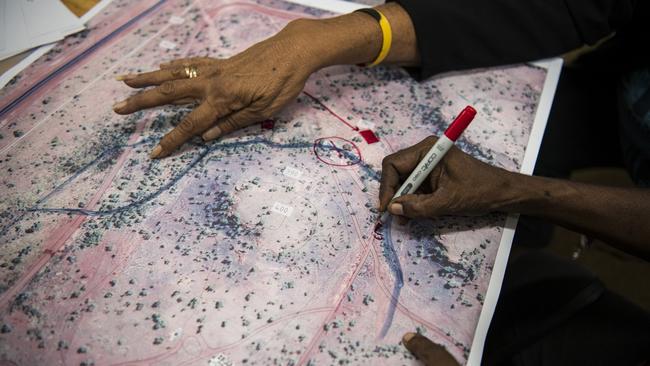

Under the Wilya Janta plan, three demonstration houses are to be built, and it’s hoped they will represent a new paradigm of Indigenous housing; one that can deal with the extremes of climate – from chilly outback winter nights to summer days when the mercury hits 40C degrees by 10am – and reflect the cultural practices of traditional Indigenous householders. Sitting with his friend Simon Quilty and family members under the shade of a eucalypt outside his house, Jupurrurla says over Zoom: “First thing we need around the community is more solars … for our people to live, it costs too much.”

It appears the Northern Territory Labor Government is listening: In May, 15 Alice Springs social housing properties were connected to solar panels and battery systems as part of a renewable energy trial aimed at generating clean power and saving residents money. The Jupurrurla family’s wishlist for their display homes includes elevated foundations to catch cross-breezes and keep out snakes, and two bathrooms placed at opposite ends of the house, so in-laws can observe kinship avoidance taboos. A fire pit would be used for cooking kangaroo, while residents would sleep east to west. Jupurrurla declares: “We can’t sleep with feet to the north or south, no. This is very important for our people. If you sleep the wrong way you wake up the wrong way. You wake up upside down.”

The community leader, his brother Jimmy Frank Jupurrurla and sister Patricia Frank Nururula are also keen on wide verandas that would provide all-day shade and accommodate relatives visiting from the bush.

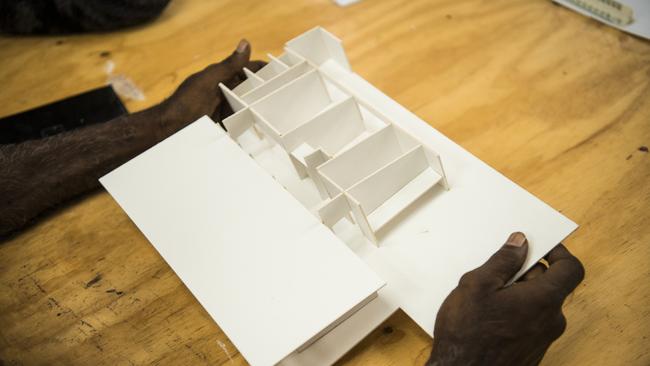

Andrew Quilty says the Jupurrurla home is “a magnet for extended family who are visiting or in need of housing’’ and this is also driving the Wilya Janta project. He photographed the home of Jupurrurla’s daughter, Nicole Frank, “where at least 21 people are currently living because of housing shortages in Tennant Creek’’. Frank is looking for a smaller home so she and her children can have what most Australian families take for granted – privacy. When built, the demonstration homes will predominantly accommodate Jupurrurla’s family on his father’s traditional land, where a 40-year lease has been secured under Native Title provisions. Architectural models have been developed pro bono and the collaborators are seeking philanthropic support to cover construction costs.

The Jupurrurlas have noticed the effects of climate change on the lands where they hunt – from waterholes drying up to goannas appearing in winter and kangaroos becoming scarce. “We couldn’t find the right food at the right season,’’ says Patricia Frank Nururula.

Despite his health problems, Norman Frank Jupurrurla is pressing on with his vision for houses which, for the first time, will reflect his people’s cultural priorities and their desire for clean, cheap and reliable energy. “We are from the community. We are the voice. We are from the grassroots and we want to see changes around our community spread right around the Territory,’’ he says.

The Big Picture is a series published in conjunction with the Climate Council

Norman Frank Jupurrurla and Dr Simon Quilty have started a GoFundMe page to raise money for the Wilya Janta housing project. Discover more: gofundme.com/f/help-warumungu-homes-stand-strong

More Coverage

Rosemary Neill is a senior writer with The Weekend Australian's Review. She has been a feature writer, oped columnist and Inquirer editor for The Australian and has won a Walkley Award for feature writing. She was a dual finalist in the 2018 Walkley Awards and a finalist in the mid-year 2019 Walkleys. Her book, White Out, was shortlisted in the NSW and Queensland Premier's Literary Awards.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout