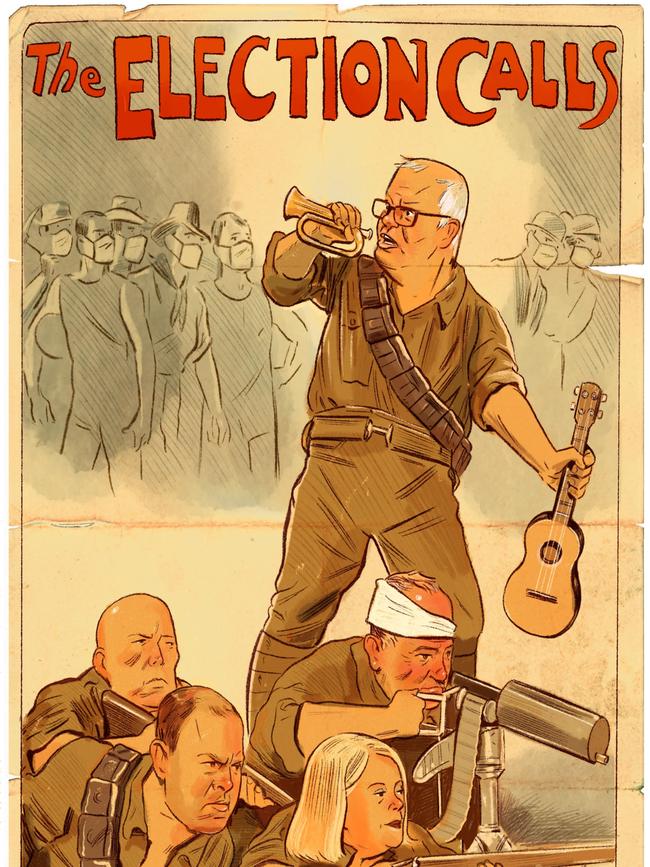

Morrison draws battle lines over Beijing

Scott Morrison’s decision to attack Labor on national security is a high-risk strategy that could easily backfire on both sides.

This will be a daunting task with many different risks. The risk for ALP leader Anthony Albanese is being branded as soft on national security, while the risk for Scott Morrison is that his three-year successful pushback against Beijing’s intimidation of Australia will now be discredited as a mere political project.

Morrison will run this campaign until voting day. The government’s deepest fear is that Albanese might win the election without having his history, values and character being brutally assessed. Above all, this campaign is driven by a huge Liberal tactical mistake – while Labor has branded Morrison for 12 months as a lying, cheap marketing man, the Morrison government has singularly failed to brand Albanese.

Now it is consumed in a panic to discredit Albanese with only three months left.

The government went soft on Albanese because it feared he might be replaced, a classic blunder. Instead, it has been outsmarted, with Albanese’s ratings now close to Morrison’s. The government’s goal is to ensure the election is not a referendum on the government but a choice between two parties and two leaders. It knows that voters will turn their gaze to the Opposition Leader at some point, and it wants to paint Albanese’s portrait first.

These tactics are a reminder of the coming campaign; hyperbole, distortion and character assassination will be prominent precisely because the serious policy and ideological differences between Morrison and Albanese are far less than normal. This is Labor’s choice.

After Bill Shorten’s 2019 defeat, Albanese runs a small-target agenda with a high-profile character destruction of Morrison. This dualism frustrates the government. But Morrison won’t be defeated easily. Having sustained what he sees as massive, unjustified assaults on his character, he intends to turn the blowtorch on Albanese.

Anything Albanese has said since his 1996 election to parliament will be seen as fair game by the government. It believes Albanese is disguising what has been his essence for much of his career. Hence the government’s assault on Albanese over China, national security and taxation. Morrison and Josh Frydenberg succeed whenever the media optics focus on the economy and security.

The upshot has been a fortnight of hyperbole, farce and accusations about appeasement and fellow travellers. It climaxed with Morrison branding Labor’s deputy leader Richard Marles a “Manchurian candidate” before having to withdraw. But Morrison then went harder. He told parliament the Chinese government had “picked their horse” in the election and, pointing at Albanese, the PM said “and he is sitting right there!” Morrison doubled down on Peter Dutton’s accusation that Albanese was “China’s pick”.

The irony is that Albanese, trying to seize the high moral ground, blundered badly on Thursday by accusing Morrison of being the Manchurian candidate, a sign perhaps that the Opposition Leader has been stung.

Australia’s current and former security and intelligence chiefs have issued remarkably strong statements directly and indirectly against Morrison. This is a near unprecedented event. Their message is that Morrison is risking the national interest.

Mike Burgess, current head of ASIO, felt compelled to speak publicly, telling the ABC’s 7.30 he was leaving politics to the politicians but saying this brand of politics is “not helpful for us”. He said foreign interference was not about “one particular party”. Burgess has a statutory obligation to be apolitical. He takes that seriously. His point is this political campaign hurts ASIO’s ability to do its job.

Former head of DFAT, Defence and ASIO Dennis Richardson, in comments to this paper and the ABC, said politicisation of the China issue damages Australia. He said “the attempt to create an artificial division where one in practice does not exist only serves the interests of one country, and that’s China”.

Richardson said the Morrison government had an “excellent record on national security” but “the government is going out of its way to create the impression of a difference where none exists. Why would any sensible government seek to create circumstances which could work against our national interest for party political purposes?

“It is a long time since an Australian government has actively sought to create a partisan divide on national security.”

Much of the foreign policy and security establishment – which has supported Morrison’s China stance – is aligned against the Morrison government’s election tactic. Currently serving senior officials are standing on their impartiality.

Former director-general of the Office of National Assessments, historian and adviser to Paul Keating, Allan Gyngell, told Inquirer: “The government is obviously pursuing short-term political advantage at the cost of the national interest. There are no great differences between the government and Labor on the issue of foreign interference, the 5G network, the Quad, AUKUS and nuclear-powered submarines.

“The attempt to create differences in the way we are now seeing is both fanciful and dangerous. It’s going to be hard enough for Australia to navigate the strategic challenges we face without the additional burden of artificial divisions being created.”

Morrison doesn’t need to run this negative campaign to buttress his diplomacy or security policies. Indeed, Labor supports his China diplomacy. His motives have nothing to do with foreign policy and everything to do with election politics.

Morrison has made a pivotal calculation – any self-harm from his negative overreach will be outweighed by the brand damage he inflicts on Albanese. That may be true. But Morrison will pay a price. He knows there must be limits on how far he pursues this attack.

The risk is apparent – that Morrison undermines his foreign policy and security reputation and invites judgments, essentially incorrect, that his entire stand against China for three years was primarily driven by domestic political self-interest.

The truth is bipartisanship on China policy has been a national asset for Australia in the teeth of China’s trade sabotage. Bipartisanship has helped to underwrite Australia’s strength. It should not be abandoned or sacrificed. A party schism in the past few years over how to manage China’s coercion would have been destructive for this country.

Morrison’s strategy of national resilience and resistance against Beijing has been of global significance, with Morrison having won the first round of this contest – ensuring that Australia did not buckle before China’s intimidation as many people suspected that it might.

The government – drawing upon the Turnbull initiatives – stood against foreign interference, banned Huawei from the 5G network, pushed for an inquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic, backed the elevation of the Quad to leaders’ level, and launched the nuclear-powered submarine initiative that was endorsed by the UK and US.

Morrison has surprised Beijing by internationalising the Australia/China crisis. He has been one of the first leaders to call out China’s tactics, telling his counterparts that Australia has been targeted by Beijing because it defied China. The three key elements in Morrison’s approach have been deepening the US alliance, strengthening our networks in the Indo-Pacific, and putting a stronger premium on national self-reliance and resilience.

Why does Morrison not just run on his national security record? With growing public apprehension of China, Morrison’s record has popular backing, widespread media support and majority endorsement within the body politic. This is Richardson’s point. Moreover, in recent weeks Australia has been the location of a Quad meeting, a critical visit by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and this week a Morrison/Boris Johnson virtual summit testifying to the diplomatic tempo Morrison has sustained for two years.

The answer to the question lies in the power of the negative. Over the past 20 years, domestic politics in Australia – and in many Western democracies – has proved that negative campaigns can destroy governments and oppositions. The early signals are that election 2022 will be a contest of negatives.

Given his tactic, Morrison had to dispute the extent of Labor’s bipartisanship on both China and security issues. He said he set the bar “high” for this test.

The reality, of course, is that absolute bipartisanship does not exist. This has been accentuated by a re-set on China policy since 2017, with both sides of politics having to shift their attitudes.

Labor’s re-positioning has been significant despite internal resistance. Its in-principle support for the nuclear-powered submarine fleet is a landmark in ALP history. It is folly to think Labor’s emotional bonds with China are extinguished. Labor’s belief that it can manage China relations better than the Coalition remains a beating impulse waiting to be tested. Morrison and Dutton don’t need to reach far into history to find critical Labor weaknesses on security, witness the failure of boat policy under Kevin Rudd and the cutting of the defence budget to 1938 levels under Julia Gillard.

Entrenched perceptions based on historical reality naturally drive much of politics, from Labor’s flaws on security to the Liberals’ flaws on Medicare.

Marles told the ABC this week there was no policy difference on China. He repeated, on Labor’s behalf, Morrison’s rhetorical criticism of China for not calling out Russia over its violent threats against Ukraine. Anybody remotely familiar with Marles’ views on strategic issues knows calling him a Manchurian candidate is ludicrous.

But don’t expect Morrison to retreat from his campaign. He told the parliament: “My government will never be the preferred partner of a foreign government that has chosen to intimidate this country. They will not find a fellow traveller when it comes to threats and coercion against Australia.”

This is wrong. There are many potential problems with Labor’s policy. But Labor is neither a fellow traveller nor an appeaser of Beijing. Such language has no place and no justification. Nor should Labor repeat it in retaliation. The nonsense about Manchurian candidates must be ditched. The government needs to beware that its hyperbole betrays its desperation – never a good look.

Finally, just remember that most Australians have another focus. Daily life is what matters. They want relief from the pandemic, health protection, economic security and, above all, having their lives return to normal.

There will lots of noise about China, but China is unlikely to be a vote switcher. The relevant question becomes: will it damage brand Albanese?

It is nearly two generations since China was an issue at an Australian national election, but the Morrison government sent the indelible message this week that it wants national security and strength against China injected into the coming election context.