There’s nothing new about angry young women

Grace Tame is promoted as the pin-up girl for a so-called new feminist order, but this sketch is hopelessly shallow.

Her fiance’s mother, Harriet, was a radical feminist in the 1970s, famous for many things, including a photo spread where she is lying stark naked on the ground, legs wide open, head perched up looking directly into the camera as the lens looks directly between her legs. It is, of course, an allusion to that other famously similar photo of Germaine Greer from the ’70s in Suck magazine.

I keep thinking of Greer as I read ever more excitable claims in the media, already congealing into an unthinking consensus, of a new form of feminism in 2022. This is the era of the angry young woman, the uncompromising one, pushing feminism in a brasher direction.

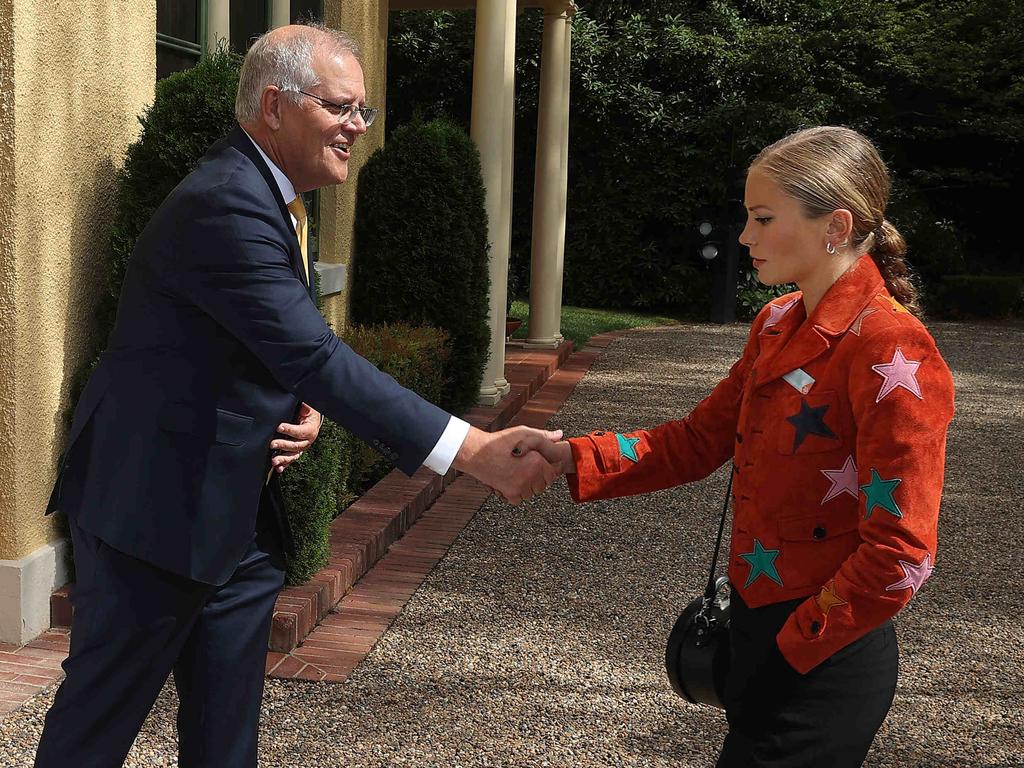

Grace Tame is promoted as the pin-up girl for this new angry feminist order. Together with Brittany Higgins and a few less credible stragglers, these women take no prisoners, appear unconcerned about dividing society with partisanship, and snub niceties to snatch a snarling headline when visiting the home of the Prime Minister and his wife.

The new angry young feminist sketch is hopelessly shallow. For starters, in a world addicted to social media, and the pursuit of likes, retweets, online hits and online “friends”, the new order is more a case of clickbait feminism, if we must settle on a label.

Older feminists who fear they have lost traction will mention Tame’s name to trade on her clickbait value. Witness Sam Mostyn, president of Corporate Executive Women citing this week the former Australian of the Year to attract attention to CEW’s same old demands. It’s like adding a touch of glitter to a drab dress to get noticed.

Those women who are busily promoting this angry new feminism as something unique and special are wrong at a more fundamental level. AYW – angry young women – are not new. Not to those who have even a passing interest in the history of feminism. Given that, it is curious to find so many older women who should be better informed about the past slavishly hawking this line about the new AYW. Either they are daft or they fear pricking the bubble of Tame’s new-found fame.

Greer was an angry young woman, but of a different order – exceedingly smart, willing to stick her finger up to all sides of politics, to the entire establishment. She wrote serious books making the case for women’s equality, she offended polite society with her brashness, her nudity, her dismissal of the 1950s housewife. As editor of Suck she advanced what became known as “sex-positive” feminism with her essays covering topics such as “Lady Love Your C..t” “Bounce Titty Bounce” and “Ladies Get on Top for Better Orgasms”. Greer is the ’70s version of our “new” AYW, only bolder and with a very big brain.

Other angry second-wave feminists “started the first refuges and rape crisis centres; occupied the courts of sexist judges; burned down sex shops; launched campaigns against the institutions of marriage”, as Finn Mackay, author of Radical Feminism: Feminist Activism in Movement, and a lecturer in sociology at the University of the West of England in Bristol, wrote recently.

In other words, the idea of angry young women voicing concerns about the treatment of women is not new. Not at all. We haven’t even talked about the militancy of Emmeline Pankhurst or Emily Davison, and other early suffragettes.

Nor is it new to see beautiful and angry women at the barricades. Gloria Steinem was determined to secure structural equality for women, and not very politely. Unlike Betty Friedan, Steinem said she “wanted to transform the system, not imitate it”.

Steinem founded magazines for feminists, set up networks for women to help them transform society by entering politics and other institutions of power. Worth noting, given the feverish delight of some when Tame and Higgins addressed the National Press Club earlier this month, Steinem blazed that trail as the first woman to speak at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, in 1972.

Nor is it new for the media to swarm around beautiful angry young women. The sass, intellect and beauty of Steinem and Greer made them media icons of the feminist movement.

As Steinem said in 2015 when promoting her book My Life on the Road, the selection of feminist leaders is like “a snake eating its own tail” – with the mainstream media still preferring white, middle-class women as “pioneers of feminism”. The base, as Steinem said in that same interview, is far more diverse.

But recognising and celebrating that diversity has long been a flaw within the cliquey world of feminism. There is still a battle over who gets to talk for women, and a patronising, forgetful tendency among the flunkies of their newly appointed “leaders” to pretend theirs is a new way for feminism. The truth is that progress for women is secured in myriad ways. We need shouty women, from time to time. We need clever ones, always.

And beyond those cohorts, we need hundreds of millions of women who live on their terms, carving out careers in their own, often quiet ways. Not all feminists are media tarts. My mother and my grandmother had no clue about Greer or Steinem yet were role models for hard work, earning their own money and caring for family. Not a bad start for the daughter of working-class migrants.

The other woman who came to mind while watching this consensus form about the new AYW is Hannah Arendt. Not a feminist like Greer or Steinem, Arendt carved out her stellar career in the male-dominated world of philosophy and political theory in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

To be sure, Arendt said some infuriating things about women. She said we are unsuited as voices of authority, which makes zero sense given Arendt’s commanding authority in her chosen fields, not least of all her contributions to 20th and 21st-century thinking about the nature of evil.

Arendt’s feminism was in the doing, ploughing through a man’s world with her sheer intellectual force, not making a fuss about being a woman. She encapsulated a mix of humility and self-confidence that today’s AYW lack.

Arendt’s distinction between “what” you are – for example, the “what” in her case was being born a woman – and “who” you are – how you fulfil yourself as a human being – is a refreshing, pragmatic, inspiring path for any woman.

When Arendt was once asked whether she felt comfortable being a woman and a professor, she said she was perfectly comfortable given she had been a woman for a long time. She had no time for celebrations as the first woman to be appointed a full-time professor at Princeton. Teaching, thinking freely, writing serious, controversial books about difficult topics, arguing logically, eschewing tribes, understanding the importance of public and private – these things defined Arendt.

Arendt’s feminism was different, uncomfortable, which meant she was snubbed by feminists who assumed their loud activism was the only way to secure female advancement.

In the ’70s, the pantheon of feminists should have been big enough to include women such as Greer and Steinem, Andrea Dworkin and others who called themselves feminists. It should have included women such as Arendt, women who bulldozed their way into male-dominated institutions in different ways, but again with big brains and sheer hard work. After all, it took all kinds of women to make it possible for future generations like mine to breathe in the air of freedom and equality with a complacency foreign to them.

Alas, the blinkered tendencies of ’70s feminism haven’t changed much. Today, a group of women, mostly in the media, talk about the women’s movement in the same cliquey way. Keen to be part of a cool new group, they pick a new pin-up, unable to look behind them or beyond them.

It is too early to judge the impact Tame and her fellow AYW, whether their voices, their anger at their experience of abuse or alleged abuse will change the lives of girls, of other women, for the better. We can only hope it does. But we sell out earlier generations of women by propagating this notion that angry young feminists are new, or that they are the only kind of feminist. The backbone of the women’s movement is formed by myriad women, their different lives reverberating down the ages, proving that the pantheon of feminists goes far beyond any one kind of woman.

In the first chapter of Monica Ali’s new book, Love Marriage, Yasmin, the main female protagonist, frets over her very conservative Indian parents meeting her fiance’s mother. And for good reason.