Max 8 has Boeing in pickle

In Australia’s dry and dusty red centre, six new aircraft worth more than $1bn are the striking new additions to a sprawling plane graveyard.

In Australia’s dry and dusty red centre, six new aircraft worth more than $1bn are the striking new additions to a sprawling plane graveyard.

Alongside ageing aircraft waiting to be repurposed or broken down for parts, the Boeing 737 Max 8s are clearly out of place, like preschoolers in a retirement home.

Owned by Singapore Airlines subsidiary Silk Air, the aircraft began arriving at Alice Springs in September, six months after the 737 Max was grounded following two fatal crashes. When they will leave is anyone’s guess.

READ MORE: Pilots, passengers never stood a chance in Boeing’s ‘flying coffins’ | Is it safe to fly? | Qantas grounds 737s

For managing director of Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage Tom Vincent, the business is a welcome upside to the tragic story that has engulfed Boeing and many others in the aviation industry this year.

He was expecting several older 737s to be placed in storage by airlines as they took delivery of their new Max aircraft. But then the planes began to crash — first Lion Air, then Ethiopian Airlines — and regulators grounded the aircraft, in a necessary move that continues to have significant ramifications for the industry.

For Vincent, the tide has turned, with the grounding now generating business for his “graveyard” in a manner he never could have imagined.

Indeed, the whole sad story of the Boeing 737 Max is almost unimaginable, from the way in which the aircraft was certified, to the decision made by Boeing to keep a new and unusual feature a secret from pilots.

MCAS, or the manoeuvring characteristics augmentation system, was added by Boeing to counter a tendency for the aircraft to pitch up at high angles of attack, because of larger-diameter engines placed higher and further forward on the wings of the updated 737.

Activation occurred when information from a single sensor indicated that the aircraft was approaching a critical angle of attack, with MCAS pushing down the nose of the plane, by directly engaging the powerful horizontal stabiliser.

In theory, it probably made a lot of sense to Boeing, but in reality the system was a disaster, largely because pilots did not know it existed.

As a result, when an MCAS activation occurred on Lion Air flight 610 in October last year because of erroneous information from a poorly repaired sensor, pilots reacted with confusion and the plane nosedived into the Java Sea. All 189 people on board were killed. The crash exposed MCAS and its disturbing capabilities but, rather than ground the aircraft and retrain pilots, the 737 Max continued to fly, resulting perhaps inevitably in another fatal accident five months later, this time in Ethiopia.

Even then it took five days for the Federal Aviation Administration to take the plane out of service in the US, after almost every other regulator, including Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority, had acted.

CASA chief executive and director of aviation safety Shane Carmody says it’s a decision he has since discussed with his counterparts at the FAA.

“The FAA’s view was they were looking at the evidentiary base and making a decision based on evidence,” Carmody says.

“I said I was making a decision based on a precautionary principle. I thought two accidents in reasonably close succession with the same aircraft was enough for me. So we had that discussion and we agreed to disagree slightly on approach.”

Carmody acknowledges the highly emotional nature of the process, given the devastating loss of life that occurred in the two crashes. In all, a total of 346 people from 35 different countries were killed in the crashes of near-new 737 Max 8s, which have since been labelled “flying coffins” by US senator Richard Blumenthal.

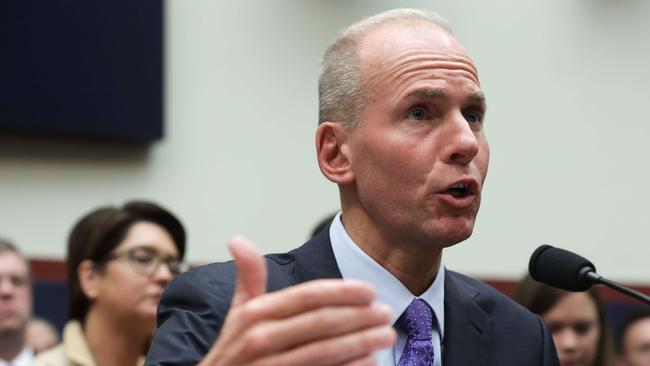

At a fiery session of the US Senate’s commerce committee this week, Blumenthal and colleagues grilled Boeing chief executive Dennis Muilenburg on the manufacturer’s decision to keep MCAS a secret from pilots, ostensibly to minimise training and have the plane certified in a timeframe that suited the sales team.

The “pilots never had a chance”, said Blumenthal, while fellow senator Tammy Duckworth told Muilenburg that Boeing “set pilots up for failure”. “We have made mistakes and we got some things wrong,” Muilenburg responded, resulting in accusations from Duckworth that he was not “telling the whole truth”.

On its own, the Max 737 has dominated a devastating year for Boeing, which has continued to churn out the aircraft at a rate of 42 a month, despite not being able to deliver any. It will ensure customers will not be kept waiting when the grounding is lifted, with more than 4500 on order.

But in a further blow to the manufacturer, this week brought news of cracking in a critical “lifetime” component of its 737 Next Generation model, known as the 737-800. It is estimated that 5 per cent of Boeing’s global fleet of 737-800s have cracks in the pickle fork — a part that helps attach the wings to the fuselage.

The problem has grounded up to 50 aircraft worldwide, including three Qantas 737-800s, and has raised more questions about Boeing’s processes and standards.

Aviation researcher Mick Gilbert points out that the pickle fork is supposed to last the life of an aircraft — or 90,000 landings. In Qantas’s case, the three aircraft identified as having cracks had each undertaken a third of that figure, at just under 27,000 landings.

“If this is a pervasive design issue whereby the part starts failing at less than one-third of its design life, that will have very serious ramifications for Boeing,” Gilbert says. “Having to change inspection schedules and then factor in replacement costs of nearly $500,000 a plane, makes a big change to the operating costs. Boeing will have to wear that cost in its entirety.”

Boeing is not saying who will bear the costs but the manufacturer is trying to work out the root cause of the pickle fork issue and finalise a repair kit as a matter of urgency.

Qantas head of engineering Christopher Snook says replacing a pickle fork is a “complex” task — possibly because of the fact it was never meant to be replaced — that will keep aircraft out of service for up to six weeks.

It is certainly not the sort of “distraction” Boeing would have liked as it strives to get the Max back into the air. Muilenburg and other key executives have touted a fourth-quarter return to service since August, but with October over and November under way, their optimism may be misplaced.

Carmody is certainly not expecting to see the Max airborne for the rest of 2019, following on from a series of face-to-face meetings with the FAA and other key regulators, including the European Aviation Safety Agency and Transport Canada.

“It’s less than eight weeks until Christmas so I think it’s a bit of a push but I would expect it to be back in the first quarter of the New Year if the regulators can all be satisfied,” Carmody says.

“Frankly, once the big half a dozen are satisfied (with the Max’s safety), I’m sure the majority will be comfortable.”

He says the widely held preference for a “co-ordinated” return to service is one he shares, but stresses there are several hurdles still to clear. “I’m well aware of the changes (Boeing) has made but I’d want to look at things like technical changes, which is point one, and also the training changes they wish to bring in, and see whether, firstly, they pass the safety test and, secondly, pass the pub test.”

By “pub test”, Carmody means the acceptance of the travelling public. Throughout the whole debacle, passengers’ perceptions of the aircraft have weighed heavily on the minds of airlines with the aircraft in their fleet or on order.

Concerns about the safety of the Max, even after a “fix” is certified, are a big part of the reason Virgin Australia chief executive Paul Scurrah negotiated a deferral of its aircraft order, to ensure the first 737 Max 8 will not arrive until 2025.

Until that time, the only Max 8s operating in Australia are likely to be those flown by other carriers, such as Silk Air and Fiji Airways, when the grounding is eventually lifted.

In the meantime, Carmody is hopeful that the aviation industry learns some important lessons from the tragic series of events to ensure they are never repeated.

“I think it’s become clear that in a certification sense not many individual authorities have the capacity to bring an aircraft like that from nothing into service without relying on industry, and so maybe the boundaries need to be redrawn slightly in terms of oversight,” he says.

“Or maybe there needs to be a much clearer understanding of what is delegated to industry and what is not. I think that’s a very big learning out of both of these tragedies.”

Back in Central Australia, it is expected more airlines will seek approval to store their Max 8s in the desert, rather than shell out for costly airport hangars, sending more business Vincent’s way.

Despite conjecture over the aircraft’s ultimate fate, he is convinced that Alice Springs will not be their final resting place.

“They’re a beautiful piece of machinery. We just want them to be safe,” he says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout