Married Catholic priest speaks out on clerical celibacy

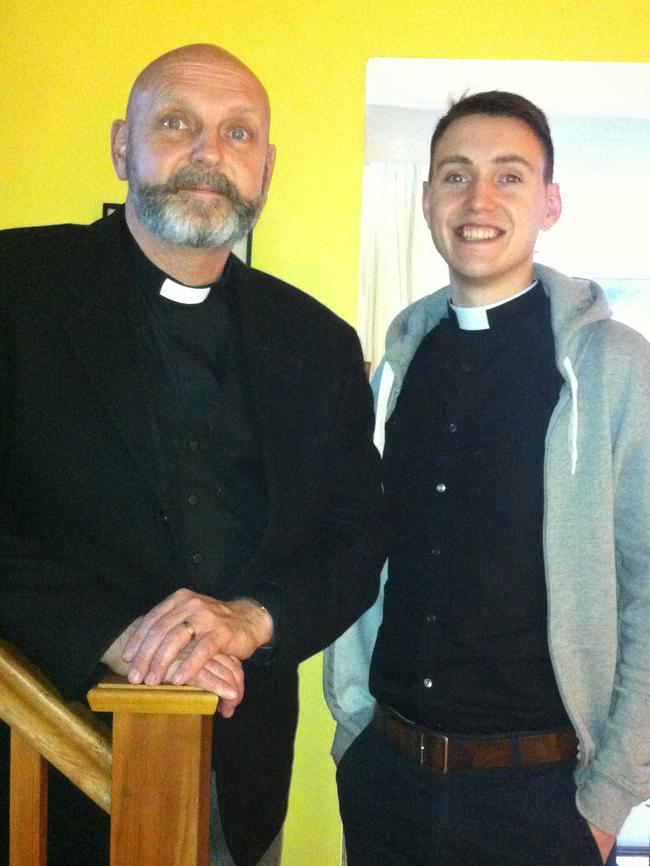

Sam Randall is the Catholic priest who seems to have it all: his vocation, the love of wife Miriam, the joy of their children and grandkids. His question for the church is why deny other clergymen that fulfilment?

Sam Randall is the Catholic priest who seems to have it all: his vocation, the love of wife Miriam, the joy of their three children and five grandkids. His question for the church is why deny other clergymen that fulfilment?

There is no easy answer, but it doesn’t stop people in and outside the Catholic faith asking whether clerical celibacy has had its day.

Rightly or wrongly, the time-honoured rule is seen to be linked to some of the keenest challenges facing the universal church as it fights to maintain relevance and influence in an increasingly indifferent world.

The scourge of child sexual abuse is the best-known and inarguably most damaging of these concerns. Australia’s royal commission into institutionalised child abuse recommended in 2017 that priestly celibacy be abandoned after hearing evidence tying it to the offending – a connection the Vatican continues to reject.

But the drumbeat for change is not fading away. Far from it when one of the nation’s most senior Catholics, Archbishop of Brisbane Mark Coleridge, told this masthead that celibacy was “very likely” to ultimately go and should be waived in the interim for married Indigenous men to make the priesthood more attractive to them.

Coleridge cited the little-known loophole that allowed Father Randall, 64, to convert from the Church of England and be ordained in the Catholic clergy while married. It’s not clear how many outside priests have made the switch in Australia. A recent count by the National Centre for Pastoral Research identified 17 former Anglican ministers who had come across, although there was no record of how many of them were married.

Now ensconced in Melbourne with Miriam – the rest of the family is in Britain and the US – Randall is adamant that they make him a better priest.

“My familial responsibilities do not detract from a priestly ministry, they enhance it and being married affords me some insight and sympathy to the challenges of family life and to gender differences,” he tells Inquirer.

“A married priest can also have a foot firmly in the world with its various challenges and opportunities through his wife and family.

“Miriam, in her domestic practical support for my priestly ministry, enables me to have more freedom and not less and my ministry is enhanced by her presence and her support and the hospitality that together we can offer to others.

“Furthermore, we are all understandably anxious about safeguarding issues and in this post-MeToo era we have rightly learned to be more sensitive to any encounter. The presence of a woman and children in the home of a married priest fundamentally alters relationships and enhances pastoral possibilities.”

Randall emphasises that he has deep respect for the tradition of clerical celibacy in the Catholic Church, formalised by the Gregorian reforms of the 11th century. “I can understand the rationale for it because it’s about commitment and making a sign of difference to the world,” he says. “I can see a place for that, I really can.”

His issue is with the compulsory application of the rule.

While the Church of Rome is by far the largest in the Catholic Communion – with an estimated 1.3 billion people worldwide professing allegiance to varying degrees, including 5.3 million Australians – Randall points out that nearly all the 23 allied churches allow priests to marry, as do Protestant denominations.

In some Eastern Catholic churches, wives are not only encouraged, but celebrated. They’re called Matushka (little mother) in the Russian Orthodox Church and Presbytera in the Greek iteration. Critically, there is a two-track path available to many Orthodox clergy: parish priests can marry, while candidates for high office – bishop and beyond – are drawn from the celibate ranks of monks.

Coleridge also cited this model in calling for a rethink of compulsory celibacy in The Weekend Australian last week, ahead of a potentially watershed Vatican summit convened by the Pope. The so-called synod on synodality in October is being billed as the most important opportunity for reform since the Vatican II council 60 years ago, bringing together bishops and delegates chosen by Francis to chart a path forward for the church.

Clerical celibacy will be on the agenda alongside the role of women in the clergy – there is a push for the entry-level role of deacon to be opened up to women, another idea canvassed by Coleridge – and outreach to the LGBTQ+ community.

Randall says the synod would do well to consider the part Miriam plays in his ministry. During his time as a parish priest, she was there when the 3am call came to help a lone woman in distress, something an unmarried priest might have baulked at. She continues to exercise her own prayer ministry for people experiencing illness or bereavement, and makes prayer-shawls.

Most mornings they celebrate Mass together and offer this to those who ask; and each evening they say the Rosary together.

“Any suggestion that my love for my wife creates some sort of internal conflict with my love for God is mistaken. There is a reason that the Lord links our love for God with our love for neighbour,” Randall says.

“God is not loved in the abstract but in the particular and in the immediate. I demonstrate my love and commitment to the Lord in my love and fidelity to Miriam, and together we demonstrate our discipleship and love for the Lord in our sacrificial service for others.”

Their story is worth telling. The son of a Kalgoorlie-born engineer and British emigre mother, Randall is from Katoomba, NSW, and grew up in the UK in an irreligious household. When he took up religious studies at secondary school, it was for the easy credit. Instead, he became hooked on the Gospels.

He had to find a church to be baptised, which turned out to be Pentecostal. Then he joined a Bible college and met Miriam, a gifted linguist, who was out from her native Switzerland studying English. After working in a hospital for the disabled – “I wanted to explore my faith,” he remembers – Randall secured a scholarship from the Church of England to read theology at Cambridge. It was a means to an end, he says, because at that time he had no interest in becoming a priest.

God had another plan. After being ordained as an Anglican minister, he volunteered to serve as a military chaplain in the first Gulf War. Later, he and Miriam would pack up the children to work as missionaries in the West Indies. He was on track to become bishop when he decided to return to full-time study for a doctoral thesis on his hero Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian who was executed by the Nazis as a resister near the end of World War II.

Randall zeroed in on how Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran, had been influenced by Catholic ecclesiology and something clicked. His pastoral work had been with the poor in downtrodden corners of northern England and the Midlands. And unlike here, the standing of the Catholic Church in Britain was “very marginal”: he found himself being drawn to it more and more.

This “quite atypical” journey led to his conversion and induction in 2019 to the Catholic priesthood. But that didn’t mean he was blind to its faults. While studying for a second doctorate in Rome – with no financial support from his new church, it should be said – Randall was astonished by the promiscuity of some of the seminarians. “The important issue is not sexual orientation but chastity,” he says, especially for an institution reeling from scandal after scandal. “The … burden the whole church carries … affects all of us. We’re all tarred with it.”

Ever the team, he and Miriam, 65, returned to Cambridge to set up a branch in England of Radio Maria, an international Catholic broadcasting service. When they were asked to establish an affiliate in Melbourne, they prayed long and hard on what do. It would mean giving up the life they had re-established after leaving the Church of England and moving away from their daughters in the UK, GP Jessica, 41, and Becky in London as well as four of their five adored grandchildren.

Ben, their 40-year-old son, was making his own way in religious life as a transplanted Church of England vicar in the US, courtesy of a move with his American wife, Rebekah, and their one child.

“They were desperate in Melbourne,” Randall remembers. “And … we felt God had called us into the Catholic Church and now he was calling us again. So we came.”

The exercise has by no means been cost-free for he and Miriam. They literally lost the roof over their heads when Randall left the Church of England as well as his pension, accrued benefits and, yes, the friends who turned on them. Since becoming Catholic – Miriam also converted – they have endured homelessness and financial distress. Unlike the celibate diocesan clergy, Randall is not housed or paid by the church. The couple don’t know what will happen after his contract expires in October.

Still, Coleridge’s intervention demonstrates that the celibacy issue is not going away, even though many Catholic traditionalists might wish it would. In the end, altering the existing model will be a decision for the pontiff; the two-part synod on synodality concluding next year can only offer advice.

To date, Francis’s record reflects his stop-start approach to reform. In 2019, a special Vatican conference on the Amazon recommended that clerical celibacy be relaxed locally to address an acute shortage of priests across the vast South American region – a precedent Coleridge drew on to propose a similar exemption for Indigenous men in Australia.

As the archbishop noted, the church’s record was underwhelming when the only Aboriginal man to be ordained was Labor senator Patrick Dodson, who lasted five years before quitting the priesthood in 1981.

The Pope kicked the can down the road, saying more “discernment” was required. The progressives’ case is that priestly celibacy is a matter of discipline, not doctrine, and could be readily changed given there was no provenance for it in the Bible or the teachings of Jesus. True enough, the traditionalists agree.

But that ignores the other implications, they say. Catholic thinker Renee Kohler-Ryan, national head of the School of Philosophy and Theology at the University of Notre Dame Australia and a non-bishop delegate to October’s Vatican synod, says the seminarians she teaches perceive great benefit in being celibate.

“Spiritually speaking, they’re really married to the church,” she explains. “They’re giving their lives to this vocation and I think we’re not good enough, generous enough, as a society in realising what a special relationship it is … and as a church we need to be very careful about losing that.”

A practising Catholic and mother of five, Kohler-Ryan accepts that the commitment to a celibate life “goes against the grain” of secular society. But that wasn’t an argument to jettison centuries of Catholic orthodoxy. “The church is not some kind of democracy,” she says. “We’re not dealing with something that is purely of human making.”

Which brings us to the thorniest question of all: the purported link between clerical celibacy and pedophilia.

The nearly five-year Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse calculated that as many as 7 per cent of Catholic priests who served in Australia between 1950 and 2009 were alleged perpetrators, a staggering number.

Des Cahill, a former priest and emeritus professor of intercultural studies at RMIT University, who undertook key research for the inquiry, says the connection isn’t causational – in other words, abstaining from sex does not of itself cause priests to offend. But celibacy is an “underlying factor” and should be addressed.

“When you look at the figures, the proportion of Anglican priests accused of abusing children is nothing like 7 per cent … and in those parts of the wider Catholic Church where priests are allowed to be married … there’s virtually no sexual abuse,” he says.

Cahill believes the Vatican needs to go beyond clerical celibacy and review the structure of the priesthood itself. In addition to embracing women, the future Catholic clergy should be made up of people who had already earned a professional qualification – “skills that would be very useful for the church’s spiritual, pastoral, liturgical and organisational work,” he says.

Asked if he regrets his decision to convert and take that long, winding road to Melbourne, Randall is typically forthright. “I know it all sounds crazy. I must be a fool for Christ, really. But speaking for Miriam … I can say our faith means everything and we believe this is what God wanted us to do.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout