Man of the times, Kissinger has some advice for Australia

The US statesman on Australia’s China dilemma, when the Ukraine war is likely to end and names the two historical leaders we most need today.

Henry Kissinger was an academic theorist and geopolitical strategist who became synonymous with high-level summitry and shuttle diplomacy, a counsellor to successive US presidents, lauded by many as a statesman and Nobel prize-winner yet loathed by others for his realpolitik approach to global affairs.

In a wide-ranging interview, the nonagenarian former US national security adviser and secretary of state to Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford discusses his new book profiling six world leaders alongside his formative years, academic career, White House tenure, and thoughts on Russia-Ukraine, China’s ambitions, US divisions and Australia’s position in the fracturing world order.

Kissinger’s life has been interlinked with critical world events from the coming to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany, World War II and the Holocaust, the Cold War and fear of nuclear armageddon, to the struggle for peace in the Middle East, the Vietnam War, detente with the Soviet Union, the opening to China and its superpower rivalry with the US.

It is this intersection with history that makes Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy such a compelling book. He combines personal encounters with historical analysis to vividly chronicle the lives of Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, Richard Nixon, Anwar Sadat, Lee Kuan Yew and Margaret Thatcher.

Each possessed the vital attributes of courage and character and were shaped by “the fiery furnace” of the 30-year period from the end of World War I to the end of World War II. They came of age as war shattered certainties and sought to redefine the purpose and direction of their countries, and contributed to the development of a new structure for world affairs.

They pursued strategies that defined themselves and the ambitions for their country and its place among the community of nations. Adenauer adopted a strategy of “humility”; for de Gaulle it was “will”; Nixon applied “equilibrium”; Sadat sought “transcendence”; Lee practised “excellence”, and Thatcher was bound by unshakeable “conviction”.

But the problem today, Kissinger says, is he cannot identify a single leader who has those essential qualities of courage, which brings virtue at the critical hours of decision, and character, which ensures dedication to values over time. Nor can he see an emerging leader to match that of the post-war era.

“You have to be optimistic about this because if it doesn’t happen, the situation will become more and more confused and world order will become more and more harder to implement,” a relaxed and reflective Kissinger says in his unmistakeable Bavarian accent via Zoom.

“In fairness, too, the great leaders may not have looked so great at earlier stages in their career.”

In 1938, at age 15, Kissinger escaped with his family from Nazi Germany, first to London and then to New York to make a new life. They met other Jewish families who had also fled Europe. It took a huge toll on his father, Louis, and mother, Paula. Because of their ages, it had less of an impact on Kissinger and his younger brother, Walter.

They did not know the horrors that were to be unleashed and would later discover that many family members were killed during the Holocaust. Kissinger never imagined he would return to Germany just six years later as a soldier in the US Army.

“I was a child when Hitler came to office,” Kissinger recalls. “All civil rights of the Jewish people in Germany were abolished and there were restrictions on where you could live. And so, it was an experience as a discriminated minority … but it didn’t have the impact on me that it had on my parents, whose lives were destroyed.”

While studying at college, Kissinger was drafted and joined the 84th Infantry Division. He landed on the same Normandy beach where Allied forces had waded ashore months earlier. He helped liberate a concentration camp at Ahlem and earned a Bronze Star for counterintelligence work that led to the busting of a Gestapo unit.

After the war, he earned a bachelor’s degree, masters and doctorate from Harvard. He drew lessons from the broad sweep of history, studying Arnold Toynbee and Oswald Spengler, together with statecraft, diplomacy and balance-of-power politics, and wrote a doctorate on the Congress of Vienna, which redrew the map of Europe in the post-Napoleonic era.

He taught government and international affairs at Harvard, and wrote several books. But Kissinger was eyeing a larger canvas, eager to influence contemporary policy. He served as consultant to the National Security Council, writing memos to John F. Kennedy, and as an adviser to New York governor Nelson Rockefeller’s 1960 and 1968 campaigns for the Republican presidential nomination.

“Working in the Kennedy White House for about 15 months taught me two things,” Kissinger says. “One, how the government operated; before that I didn’t really know how the security adviser conducts himself because it was a relatively new position in the American government. And, secondly, it showed me the complexity of the process of decision-making.”

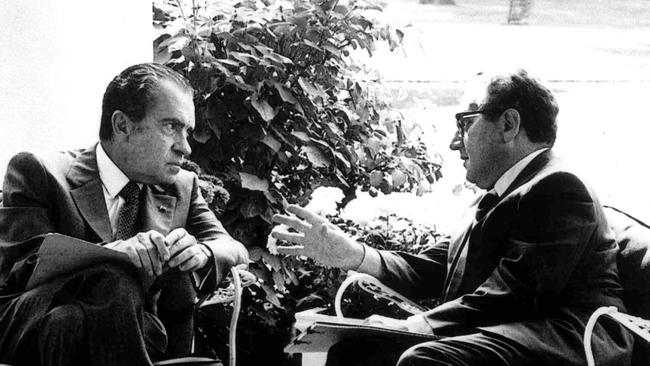

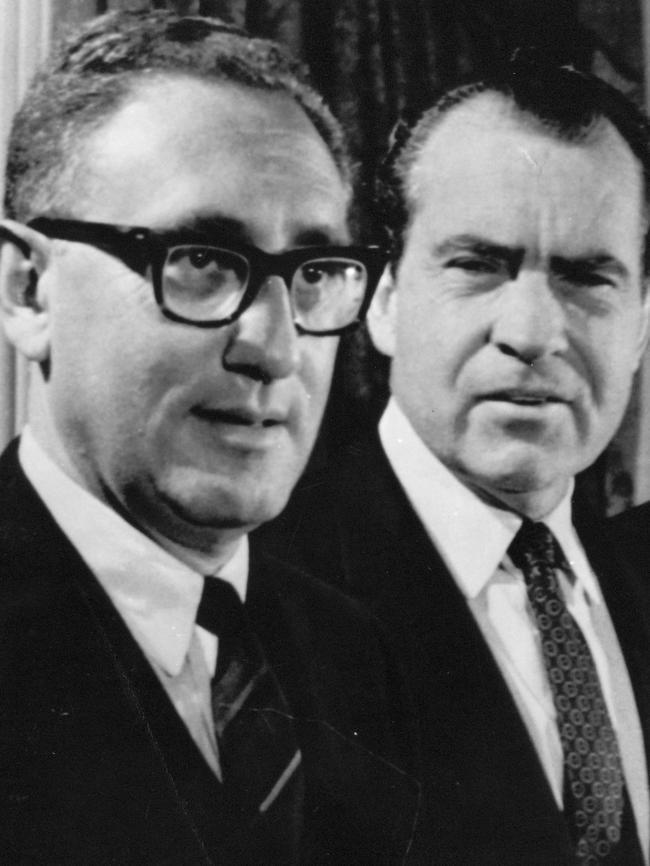

Kissinger did not know Nixon well before being offered the position of national security adviser. He initially baulked at the invitation. Rockefeller urged him to accept. Kissinger soon found that Nixon was “the best prepared” incoming president on foreign policy since Theodore Roosevelt.

“Nixon had an unusual understanding of the strategic elements that were involved in policymaking and so from that point of view he was the most unique American leader, and he had great courage in implementing his convictions,” Kissinger judged.

Kissinger, short, stocky and curly-haired with trademark horn-rimmed glasses, became a global celebrity in his own right. Although the White House was simmering with animosity and suspicion, and Nixon and Kissinger secretly recorded phone conversations, even with each other, Kissinger says they formed a close “partnership” that grew personally warmer over time. He credits Nixon with taking the US from “faltering dominance to creative leadership” around the world.

“There was no real rivalry between us but, given the passions of the period, the media had a tendency to give me maybe undue credit for individual decisions,” Kissinger says. “Whatever contribution I made could not have been made in the absence of a strong and thoughtful president.”

They inherited the Vietnam War, which destroyed Lyndon Johnson’s presidency and divided Americans. Nixon promised “peace with honour”. The task, Kissinger saw it, was “navigating between victory and defeat”. He defends the conduct of the war and the peace settlement even though they intensified the conflict knowing victory was unlikely. They wanted to force North Vietnam to the negotiating table. The secret bombing of Cambodia killed about 100,000 people and devastated the country.

“There were North Vietnamese divisions on Cambodian territory which were killing Americans daily, (so) the basic structure of our policy was correct,” Kissinger maintains. “Every American president, having to deal with this kind of war, has carried it out in roughly the same manner. But, no doubt, we could have handled some things more skilfully.” The Paris Accords, Kissinger argues, “depended on the willingness” of congress “to enforce its provisions”. But lawmakers reduced economic and military assistance to South Vietnam, and refused to authorise US airpower across Indochina. The North overran the South and Saigon fell in 1975.

It is 50 years since Nixon met Mao Zedong. Kissinger led the secret negotiations with China, visiting in 1971, and paving the way for Nixon’s trip the following year. Kissinger, who had five meetings with Mao, says the strategy was to have the US closer to China and the Soviet Union than they were to each other.

“China was strategically much weaker than the US and the greatest threat to the balance in the world order was the Soviet Union,” Kissinger explains. “This co-operation between China and the US lasted until little more than a decade ago, and now a new situation exists.”

Competition between the US and China is likely to be economic rather than military, Kissinger suggests. But how the US and its allies such as Australia deal with China is “a historic task”. With Taiwan a flashpoint, Kissinger urges a “cooling” of rhetoric by the US and China because it makes the situation more “tense” and heightens the risk of conflict.

Describing Australia as part of the “complex tapestry” in Asia-Pacific region, Kissinger believes we should continue to deepen relations with the US; he welcomes the Quad with the US, India and Japan; and encourages continued dialogue with China.

“Australia, as an American ally, is entitled to the protection of its security and therefore its close strategic co-operation with the US,” he says. On China, Kissinger adds: “The dialogue can take place in which the two sides are trusting in their conduct towards each other to prevent accidents and unnecessary confrontation.”

Russia’s need to “dominate its surroundings” and its “expansionist urge” is fundamental to its security, Kissinger says. He has met Vladimir Putin many times since the 1990s. He says Putin has a “mystic” view of Russia, believing its strength comes from its resilience and laments the break-up of the Soviet Union. He doubts Russia can continue to wage war with Ukraine long-term. He recently suggested the conflict might cease with Russia returning to the “status quo” as in before February when Crimea had been annexed and Donetsk and Luhansk were controlled by Russian separatists. He believes Russia would see this as a victory but in reality, it is a defeat.

“The question is: should it be fought to the absolute exhaustion of all participants or whether at some point there will be a discussion after which Ukraine, Russia and Europe can live together,” Kissinger says. “I expect there to be a diplomatic effort. My instincts say it will happen sometime this year. There is no ambient sign of this happening yet.”

Kissinger remains a realist and pragmatist in the conduct of foreign relations in pursuit of a more stable world order. He has long argued that countries need to accommodate the interests of other countries within the limits of what is acceptable against national values. He places a premium on discussion and negotiation, especially in an age of artificial intelligence weaponry, which is more dangerous than the risk of nuclear conflict during the Cold War. “Russia and the US permitted themselves to be defeated by non-nuclear countries without resorting to nuclear weapons,” Kissinger says. “Hi-tech countries should not get themselves involved in a war with each other and have an obligation … to remain in dialogue with each other to prevent it. This is not yet happening and therefore the danger of a military conflict is greater than should be.”

The cover-up of the break-in at Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Office Building by Republican Party operatives resulted in Nixon’s resignation in 1974. Kissinger describes Nixon’s downfall as a “tragedy” as the inner demons of insecurity, paranoia and hate overwhelmed him.

“Some people in the administration were afraid that he might make a coup,” Kissinger recalls. “There was never any such thought … Nixon knew that he was partly responsible for what had happened and that it was not something that was imposed on him. It grew out of mistakes he had made and the atmospheres he had created.”

Nixon’s resignation letter was written to Kissinger as secretary of state, who had been appointed to that position in 1973 and remained national security adviser. It was, for Kissinger, a sad end to a consequential presidency that changed the world. He recalls the final night of the Nixon presidency. Summoned to the White House, Kissinger found Nixon alone in the Lincoln Sitting Room. He was seated on a lounge chair with his legs on a settee and yellow legal pad on his lap. The president was “distraught” and in “agony”. They spoke for almost three hours and prayed in the Lincoln Bedroom as the clock ticked towards midnight.

“He wanted to go over with me what had happened in his administration and how history would deal with it,” Kissinger recollects. “I said to him, ‘History will treat you better than your contemporaries did’. And so, this was really the theme of that evening.

“He invited me to a short prayer – he didn’t define what faith he was praying to – but he did it with the conviction that, however God was expressed in the various religions, he could recognise what was sincere. But this was not a melodramatic event; it was sort of a conclusion to a meeting that was very moving because here he had appointed the chief adviser of his principal rival (Rockefeller) to join him as his national security adviser.”

Kissinger, who served Ford as secretary of state until 1977, notes Dean Acheson once said retired leaders often reflect on “alternative course of action” they could have taken. So, I ask Kissinger if he regretted any actions, or failures of action, regarding Indochina, the coup in Chile, the invasion of East Timor or any of the other controversies during his tenure.

“We certainly don’t claim to be infallible,” he responds. “We tried not to do impetuous things and in almost every case thought through our issues carefully, which doesn’t preclude that other points of view may not have some validity, but on the key issues we tried to act responsibly towards people who differed with us and towards the way history would look at what we did.”

In the 45 years since Kissinger left government, his counsel has been sought by every president from Jimmy Carter to Donald Trump (he met Joe Biden as vice-president) and countless world leaders. He has “compassion” for all the presidents he has known given the “pressures” they face. Asked to nominate who would have made a great president, he offers two: Rockefeller and John McCain.

Today, the US faces an outlook like that when Nixon took office. “It is a tale first of exuberant confidence generating overextension and then of overextension giving birth to debilitating self-doubt,” Kissinger writes. The US faces challenges to its strategies and values, and “there is renewed potential for catastrophic confrontation”.

There is little comparison between Nixon’s attempted cover-up of the Watergate burglary and Trump’s attempt to overturn an election, Kissinger says. He is appalled by Trump’s behaviour and troubled by divisions in the US at a time when the rules-based order is under strain.

“These (January 6th Committee) hearings that are now taking place are not about an attempt to carry out American politics by inappropriate means but an attempt to undo a constitutional process,” he says. “We were lucky that Gerald Ford as vice-president and then president was a man who brought about a greater degree of moral cohesion. Right now, we have not yet found the anchor point of cohesion in America.”

Kissinger is right that leadership, especially in the political arena, alters the destiny of nations. Human agency is often the driving force of change. He is an advocate for “transformative” leadership, categorised as “statesmen” or “prophets”, who transcend crises and “raise their society to their visions”. His six case studies – Adenauer, de Gaulle, Nixon, Sadat, Lee and Thatcher – illustrate this. Each of them had qualities that are in short supply today.

But asked which leader we most need today, Kissinger names de Gaulle and Thatcher. “They understood their own societies very well and so they knew how to formulate their politics in a way that they would likely win support,” he says. De Gaulle, he adds, understood “how to gain power and how to use it” and Thatcher had convictions that she defended so “the middle ground would move towards her”.

At 99, Kissinger remains sharp with a remarkable recall of people and events, and an informed and perceptive take on global issues. He remains an ever-present figure on the world stage, sometimes controversial but with unique authority.

So, after an hour-long tour d’horizon, I ask the secret to living a long and productive life?

“Two things: choose your parents well,” he says with a smile. “Both my parents lived into their late 90s, an ambition I never had explicitly, but I am happy to take it.”

Henry Kissinger’s Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy is published by Allen Lane.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout