Listen to the voices as they call for constitutional action on an Indigenous Voice

There is emphatic support for an enshrined Voice from a broad church of Australians. From truck drivers, elderly Australians, young Australians with disabilities, sporting organisations, Catholics and Baptists and other religious organisations, unions, multicultural groups, corporate Australia, Aboriginal land councils, the Law Council of Australia and the Business Council of Australia. Submissions have come from every walk of life and political persuasion.

This Co-Design process had invited public submissions from the Indigenous community and the Australian public on the 239-page Interim report released by the group chaired by Professor Marcia Langton and Tom Calma. Submissions were extended by a month because of poor engagement by the end users in the process, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The process has been rushed, the report complicated to read for many people, and major Aboriginal organisations like the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, the Central Land Council and many others have criticised the process for failing to account for self-determination with many facets of the Voice pre-ordained.

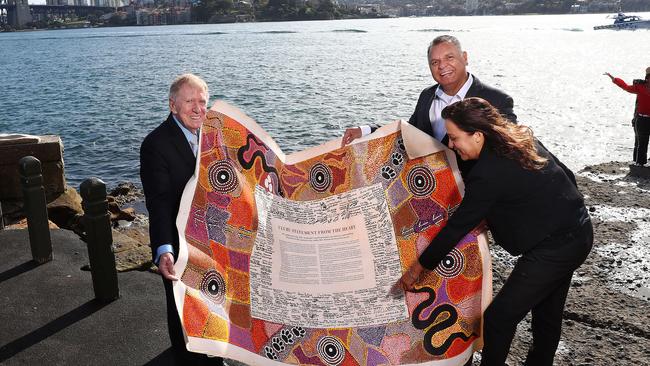

By way of background, the Voice Co-Design process exists because of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Prior to the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the Referendum Council, no one was calling for a “Voice” to the parliament, enshrined or statutory. This was recommended by the Joint Select parliamentary committee chaired by Senator Patrick Dodson and Julian Leeser MP. The committee was set up despite Malcolm Turnbull’s rejection of a voice to parliament to study the Referendum Council’s recommendations and also, the process of the deliberative dialogues that led to the issuing of the Uluru Statement. The joint select committee found that the dialogue process was legitimate and supported and that the Voice to parliament was the only viable form of symbolic and constitutional recognition. The committee recommended a two-stage process. First, a Co-Design process to put meat on the bones of the Voice seeking the views of all Australians. Second, following the report there will be discussion of what legal form best suits the Voice.

While the Morrison government has repeatedly committed to the “two stage process” of the parliamentary committee including in their election platform and 2020 Closing the Gap speech, Wyatt has prohibited consideration of the constitutional form and is pursuing a legislated voice only. The Australian public do not agree.

The Indigenous Law Centre at UNSW is conducting a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the submissions in response to the Indigenous Voice Interim Report. There are 2487 submissions with many more to be uploaded but 87 per cent of public submissions published to date support a referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Most of the submissions are from non-indigenous Australians and this is balanced by the fact the bulk of the consultations involve Indigenous Australians.

The public submissions and consultations have highlighted how unscrutinised the assertion is that the Voice can be easily enshrined after it is legislated first. It may give comfort to some but is problematic and it needs to be contested. It is not true to say that a referendum will automatically follow a legislated model nor that it could. This assertion falls effortlessly off the tongue for those disinterested parties who think “anything is better than nothing”. As one of the Aboriginal public lawyers involved in the deliberative dialogues has said in response to the “anything is better than nothing” argument, is that it is a “subtle but entrenched racism of lowered expectations (that) continues to rear its ugly head — even among our own mob”.

Many people have intimated that perhaps the legislative route is better than nothing — truth be told, if I had not been present at all 12 regional dialogues and at the Uluru convention, I might be inclined to follow such advice. But I would not be so bold as to question the call of more than 1000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members who dedicated much diligence to learn about constitutional reform, putting aside their disenchantment, and picturing a better future for the generations to come.

Proponents of the “try before you buy” approach say that by legislating first, you can make sure that the Voice works before you put it in the constitution. The most essential measure of the Voice’s success will be that it effectively holds parliament and the government to account for their performance in Indigenous affairs. Does anyone seriously think that a government which has been effectively held to account by a First Nations Voice will want to give it more legitimacy, independence and permanence by writing it into the constitution? It’s almost inconceivable.

On the other hand, if the legislated Voice does not work effectively, who is going to want to enshrine it in the constitution? Again, we would have one particular, flawed model of the Voice discrediting the bigger, more fundamental idea — that First Nations peoples should have a voice to parliament — and killing off the chance that the bigger idea will be included in the constitution.

It does not follow that if you support constitutional enshrinement of a First Nations Voice, we will eventually get there by legislating first. You are predetermining that constitutional enshrinement will not happen because if it is successful, it won’t be strengthened, and if it isn’t successful, they won’t enshrine. Meanwhile Labor this week says it is supporting Uluru and a referendum but is predetermining that constitutional enshrinement will not happen because it supports legislation first.

University of NSW law academic Gemma McKinnon has argued that the “try-before-you-buy method”, on the basis that Australians will not vote for a constitutional First Nations Voice until they have first heard it and seen it in action is like asking us to audition before we get recognition: “We have to prove that we can be civilised and not interfere with the status quo.” Many forget that the founding fathers of the constitution allowed for constitutional amendment to be part of the democratic process. It is set out in the constitution for parliament to pass a bill setting out the amendment and a question to Australian electors at a referendum, but the constitution does not say you need all legislative detail prior to a referendum. Many forget that a part of the Uluru work was the deferring of the features of the Voice to parliament as a nod to parliamentary sovereignty. Are politicians revealing a distrust of themselves? The constitutional amendment is relatively short and sweet. The details of the voice will be legislated by parliamentarians elected by the Australian people through the country’s democratic process.

People talk about the risks of enshrining the Voice but few speak about the risks if it is not. This is the 11th year of constitutional recognition and we have had seven Commonwealth processes and nine reports. There is much greater risk in the status quo. Professor Rosalind Dixon once wrote that “the risk in the status quo is a whole generation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will entirely lose faith in the process of legal and constitutional reform … there is a real sense that this is the last chance we get for a generation to fix this and so that the small risk that one runs of changing things … has to be weighed against the absolutely certain risk of disillusioning and disappointing a whole generation of leaders and fellow members of our community”.

And this is my concern. The overwhelming support of the Australian people for a referendum is clear in polling over four years and in the public submissions to the Voice committee, authored by fellow Australians from all walks of life. If it was to be ignored by the Co-Design group and the politicians, in plain view, it would only entrench further the voicelessness and powerlessness that drives the disadvantage in our communities.

Professor Megan Davis is a Cobble Cobble Aboriginal woman, the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law and was a member for the Referendum Council.

If the Prime Minister wanted confidence that there is a groundswell of Australian support before proceeding on a referendum for an Indigenous Voice, he need look no further than the public submissions to the government’s Voice Co-Design process. Even though Indigenous Australians Minister Ken Wyatt banned his hand-picked co-design group from discussing the Uluru Statement from the Heart and prohibited discussion of constitutional models for a Voice, the Australian community’s desire for a referendum has overwhelmed both face-to-face consultations and written submissions. As of noon Friday, with almost 2500 submissions uploaded, support and in-principle support for constitutional enshrinement is running at 87 per cent of the submissions.