‘50 years later, I still feel a sense of shame and regret’

We failed the South Vietnamese who worked for Australia when Canberra abandoned them to their fate on April 25, 1975.

Saigon, Anzac Day, April 25, 1975. Across the city, white cars and vans flying Australian flags moved through anxious crowds towards designated pick-up points. The air was hot and heavy with the promise of monsoon rain and the passengers, crammed between boxes of files and personal baggage, were cramped and sweaty.

They were diplomats, consular staff, a few businessmen and a handful of journalists. At each rendezvous they left behind small groups of Vietnamese staff and former local friends desperate to flee the city.

The embassy drivers wove through masses of cyclos, mopeds and beetling blue and yellow Renault taxis. Incongruously, amid frenzied traffic, female road workers were building barricades of cement-filled barrels. Otherwise there was a strange lack of military activity.

The convoy was headed towards Tan Son Nhut airport where two RAAF Hercules planes were waiting to make the last Australian flights out of South Vietnam.

At Ben Cat, a hamlet on Highway 13 not far to the north of Saigon, North Vietnamese Army commanders were finalising the timetable for the final assault on South Vietnam’s encircled capital.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees were crowding the highways and seaports as they fled south on foot or by boat. The “convoy of tears” followed the fall of the major northern cities of Da Nang, Hue and Nha Trang.

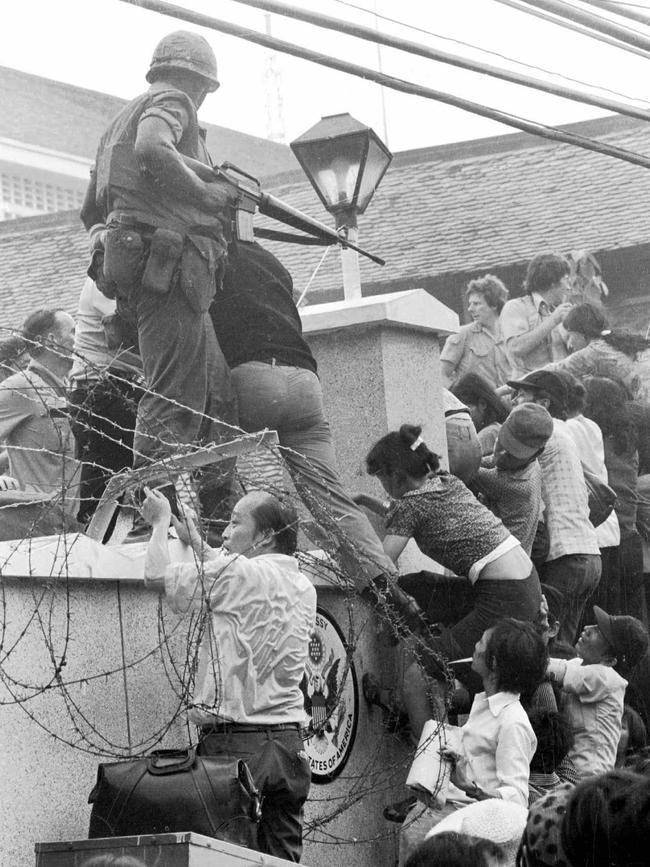

Inside the white walls of the American embassy in Saigon, the CIA station chief was arranging cars to ferry former president Nguyen Van Thieu that night to the US Air Force plane that would fly him to Taiwan.

Just weeks earlier, ABC cameraman David Brill and I had filmed a defeated and isolated Thieu in his office meeting federal opposition frontbenchers Andrew Peacock and Ian Sinclair on their last-minute, grandstanding fact-finding mission to Cambodia and Vietnam.

Now the embassy cars in which we’d travelled to Independence Palace were taking us to the airport to be evacuated to Bangkok.

Foreigners had been fleeing Saigon for weeks and the major embassies were down to skeleton staffs. The evening before, Canberra had ordered the evacuation of the remaining Australian embassy staff. Last to go would be the Americans when Saigon fell to the victorious North Vietnamese forces on April 30.

Hours earlier, Australian ambassador Geoffrey Price locked his official residence on Rue Pasteur and left the house and the family dog in the care of his trusted local cook, Mr Ba. For Price, it was an inevitable but unsatisfactory end to weeks of procrastination and indecision by the Whitlam government in the face of unrelenting diplomatic pressure from Hanoi.

Most disturbing for the embassy staff, the government specifically excluded South Vietnamese from the evacuation unless they had completed local immigration formalities. Given that Canberra had slowed the process to a trickle in the dying days of the war, the skeleton staff of Australian diplomats still in Saigon knew this meant leaving behind hundreds of South Vietnamese who were trapped in Saigon’s bureaucratic pipeline. The telexes were still chattering out names as communications were shut down soon after lunch on Anzac Day.

On the seventh floor of the Caravelle Building on Lam Son Square, Mrs Minh, the receptionist at the Australian embassy, remained at her post. Fighting back tears, she was telling frantic phone callers the embassy was no longer processing visas. It had nothing to do with the Anzac Day holiday. Australia had shut up shop.

On the Australian embassy balcony overlooking the National Assembly and the Continental Palace Hotel where Graham Greene had drafted The Quiet American, Brill filmed the Australian flag being lowered, folded and handed to ambassador Price. He carried it indoors and, still holding it, dictated a final telex message to Canberra. It included a wry comment about the trying times his staff had faced in recent weeks; it thanked Foreign Affairs staff for their help and ended with the words “Goodbye from Saigon”.

Price’s final act within the embassy chancery was to tell Mrs Minh not to answer any more phone calls and to make her way home. It was around one o’clock in the afternoon. Price had waited day after day for a list of approved visa applications. It did not come until two days before the Australian evacuation. The ambassador was told that no Vietnamese were to be flown out of the city on board the Australian evacuation aircraft without proper papers.

By then, in a city where the local bureaucracy had collapsed, it was too late for the lucky few to get departure permits from the South Vietnamese authorities.

The enormity of the Australian departure for the loyal Vietnamese staff had become clear well before Canberra gave the order to withdraw. The Whitlam Labor government line was that embassy employees had nothing to fear from Hanoi’s takeover of South Vietnam. This was in direct conflict with Price’s view from Saigon. His daily diplomatic cables to Canberra were largely ignored.

The ambassador’s problems started when prime minister Gough Whitlam took personal control of Vietnam policy on April 2, 1975 – just after an ABC television news report shot by Brill and Peter Munckton showed armed South Vietnamese soldiers storming one of the RAAF relief aircraft picking up refugees at Phan Rang.

The role of the six Australian transport planes, nominally assigned to a UN humanitarian effort in South Vietnam, suddenly became an international and domestic issue for Whitlam. He banned the ABC news team in Saigon from travelling on the RAAF aircraft.

It became clear that Hanoi was closely monitoring the movement of the Australian airlifts, complaining that moving refugees was aiding South Vietnamese military efforts. As the Whitlam government juggled diplomacy between the two Vietnams, the victorious North was enjoying a new era of influence. They had a strong argument. Any student of military strategy knows that a panicked civilian population becomes part of the battlefield equation. Canberra was in a no-win situation.

The result was that the Australian military aircraft spent a lot of time waiting to start their evacuation role. As Tan Son Nhat airport became more vulnerable to attack, the planes were flown out of Vietnam to the safety of Bangkok or Butterworth each night.

In the meantime, embassy staff members were pushing Canberra to speed up the growing backlog of South Vietnamese families wanting to be resettled in Australia. Many South Vietnamese wanted to join family members already there. Others had special claims because of associations with the Australian military forces or the embassy that might lead to reprisals after a North Vietnamese victory. The Americans were busy painting a bloodbath scenario. Australian staff in Saigon certainly believed this could be an extreme possibility. They argued that such people should be given priority consideration.

Canberra, however, had been more interested in babies. Whitlam, who had been quoted as saying he was “unmoved” by Vietnamese sob stories, had a particular interest in the well-publicised “baby lifts” in which plane-loads of orphans were flown out of South Vietnam to Europe, the US and Australia.

Front-page newspaper photos of the prime minister cuddling tiny new arrivals enraged his embassy staff in Saigon, who had been instructed to comb the city’s orphanages to find enough babies to fill two flights to Australia. There was resentment of what they called political window-dressing. It grew to anger on the crash of the giant US Air Force C-5 Galaxy taking babies on a similar flight to the US.

Most experienced diplomats understood that the Vietnamese tradition of extended family meant many children were placed in orphanages as a temporary measure by parents caught up by the tragedies of the war. The plight of adult Vietnamese and their families seemed to strike no chord with Canberra.

The small Anzac Day convoy moved slowly through the snarled Saigon traffic towards the airport, negotiating police and army check points. The embassy cars swung by the monument at the gates of Tan Son Nhut. The inscription “The noble sacrifice of the Allied soldiers will never be forgotten” seemed somewhat hollow. The nervous Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers knew their former allies were abandoning them and there was resentment in their surly check of credentials.

On the tarmac there were emotional farewells as embassy staff thanked the local employees who’d driven them to the airport. The locals were well aware that the government in Canberra had ordered they be left to an uncertain fate. An emotional ambassador Price handed the keys of his embassy Citroen to his driver, Mr Thuoi. Other convoy drivers were given the keys to their cars in a manner that suggested they were gifts. I later found out departing embassy staff had personally given the remaining local staff all their Vietnamese and US currency.

Brill filmed Price as the last person to board the plane. Price had insisted he wanted to be the last to leave. Brill pointed out to him that, to get the shot, the camera and its operator needed to be on the tarmac. He ended up boarding after the ambassador. The local staff who had driven us to the airport stood by their newly given cars as the plane started its engines.

Inside the cavernous belly of our RAAF Hercules there were plenty of spare seats. There was even room for several cages of pets being flown out to Bangkok for UN personnel leaving with the Australians. Only one Vietnamese embassy employee, a man recognised as being at risk if left behind, was on the plane together with his wife and child.

As well as the ABC team – cameraman Brill, reporters Munckton, Tony Joyce and me – the Hercules was carrying all but one of the few remaining Australian journalists who had been reporting from Saigon. That exception was NBC/Visnews cameraman Neil Davis, who was to film the first NVA tank smashing through the gates of Independence Palace – an image that came to depict the North Vietnamese victory.

Seated farther down the plane was my friend and Hong Kong colleague Derek Williams, then a sound recordist for American television network CBS. A New Zealander, Williams was accompanied by one of the few Vietnamese to leave in the Australian evacuation. Amid the confusion and bungling bureaucracy of the defeated regime, Williams managed to marry his long-time girlfriend, Ha, a senior stewardess with Air Vietnam, just days before. Her new passport was the last to be issued by New Zealand’s embassy.

The Australian Hercules took off from Tan San Nhut late on the afternoon of April 25 bound for Bangkok. For all on board, it was a depressing and sad departure from a country that Australia had once fought for and supported as an ally. The irony that it was Anzac Day was lost on no one.

The evacuation stories filed from the ABC’s Bangkok office that evening reflected my own anger and shame in the way we departed Saigon. I knew embassy staff members also were upset at their inglorious departure. I tended to lay some of the blame with ambassador Price, who steadfastly refused to comment about the abandonment of local staff or the very small number of Vietnamese who had been processed for entry to Australia.

I later came into possession of some of the cables that had been exchanged between Canberra and Saigon in April 1975. They made it clear that Price and his embassy had argued strongly against the strict instructions from the Whitlam government to delay the visa process and not to take out any local embassy staff on the evacuation. It was evident that Whitlam, who’d taken personal charge of Vietnam policy, had decided to keep Hanoi on side at the expense of the defeated South Vietnam.

I finally interviewed Price for the ABC’s The World Today program 20 years after our last flight out of Saigon. He confirmed what I’d learned well after the evacuation: that the embassy had fought an unsuccessful rearguard action against the instructions from Canberra. “It seemed to me that the prime minister was not eager to do anything that would open the gates to a rush of refugees to Australia,” Price told me in 1995.

“Whitlam, or his government, certainly delayed sending us the lists of approved entrants for resettlement in Australia until the last days. By then I was under instructions to leave. I couldn’t do anything about them.”

The former ambassador’s account was backed by the findings of a Senate standing committee on foreign affairs and defence inquiry into the government’s handling of the Saigon evacuation.

“We are unable to come to any conclusion other than one of deliberate delay in order to minimise the number of refugees with which Australia would have to concern itself,” the report found.

Price, ever the diplomat, remained circumspect when I asked him whether he was still resentful of the role played by Whitlam. “I don’t want to talk, 20 years later, of resentment,” he said. “But I was very distressed at the time.”

Before his death in 1999, Price summed up his feelings in a newspaper article: “We should have been more generous and sympathetic to our loyal employees. Shamefully, we were not.”

Fifty years later, I still feel the same sense of shame and regret on the events of that Anzac Day. It was not Australia’s finest hour.

This is an edited extract from an unpublished memoir by former ABC correspondent Richard Palfreyman.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout