Libs need compassionate conservatism to end ‘nasty party’ reputation

The Liberal Party needs to reform its right flank into a contemporary, compassionate conservatism, devoted to fostering the common good and Australian national interest through universal human values.

In the wake of the Liberal Party’s humiliating defeat at the May 3 election, former senator Simon Birmingham posted a kind of 21st-century epistle on LinkedIn, discerning the electorate’s crisis of faith in “the broad church”.

“The Liberal Party is not seen as remotely liberal and the brand of conservatism projected is clearly perceived as too harsh and out of touch,” he wrote, echoing Theresa May’s 2002 warning to Britain’s Tories that they were seen as “the nasty party”.

Who could seriously disagree with this assessment, other than to note that both the liberal and conservative wings of the party bear responsibility for that perception?

Reasonable minds may disagree on the party’s future direction out of the ashes. Many of Birmingham’s proposed structural and cultural reforms are sound and long overdue, including the need to revitalise membership and community engagement, restore the party’s connection with women and urban voters, and reform its model of liberalism to reclaim the political centre.

But he was largely silent on the need to reform the party’s conservative tradition, as an indispensable pillar of the “broad church” since its foundation in 1944. If the party is to avoid repeating the prolonged period of opposition in the 1980s and 90s and the internecine wars between its liberal and conservative elements, a rebalancing of the party’s foundational values and policies is needed.

Both wings have failed, and neither has the answers alone. This re-anchoring of the party’s shared philosophical centre should include a contemporary compassionate conservatism alongside a community-focused liberalism.

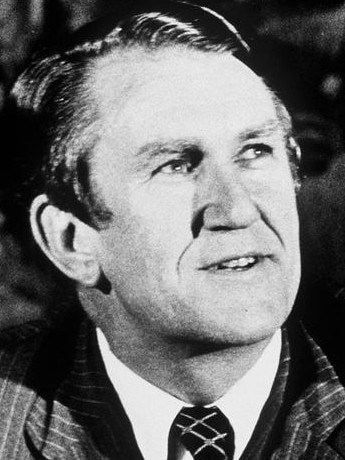

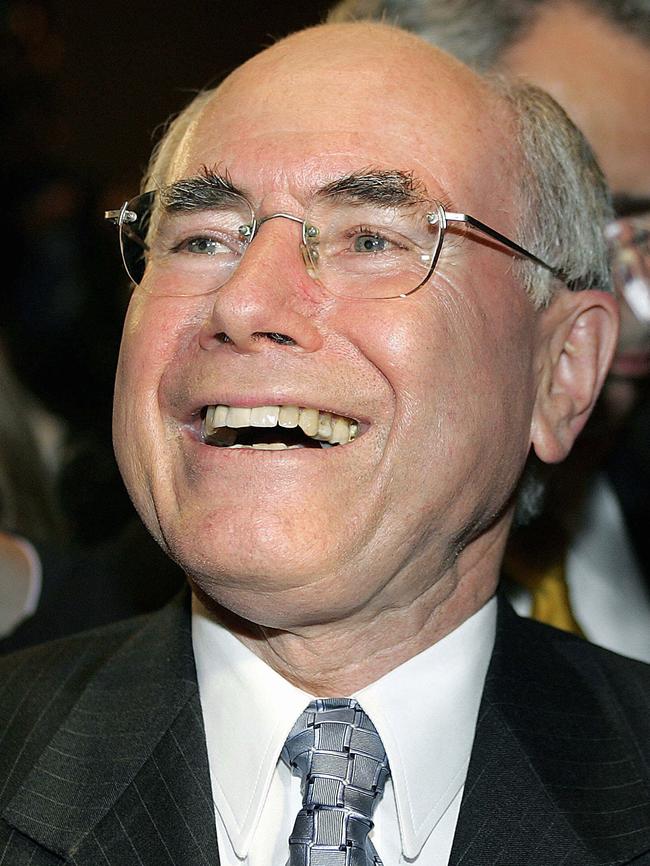

It was John Howard who coined the Liberal Party as a “broad church” and referred to its supporters as the custodians of both the classical liberal and conservative philosophical traditions. This has generally played out as a dynamic equilibrium between a Millian commitment to individual freedoms, smaller government and laissez-faire economics, and a Burkean veneration of the family, small business, incremental change and institutions.

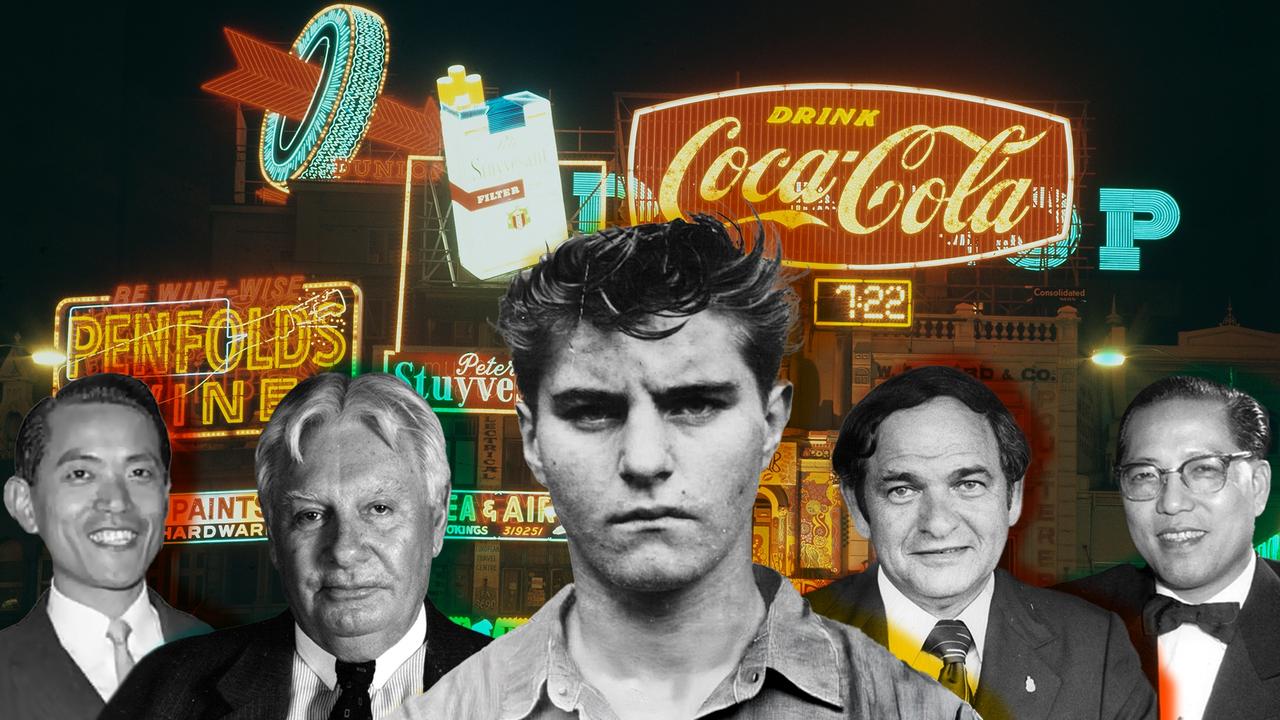

The strength and coherence of the conservative wing of the party is critically important to the success of the Liberal Party as a whole. Only four Liberal leaders have led the party into power from opposition: Robert Menzies in 1949, Malcolm Fraser in 1975, John Howard in 1996 and Tony Abbott in 2013.

Each was firmly rooted in the conservative traditions of the party and maintained good relations with the National Party. The recent Coalition fracture has underscored the critical importance of the Liberal leadership as the nexus of centre-right politics in Australia. If the Liberal Party (and Coalition) is to win government again, it’s more important that its conservative hinterland is reformed and made relevant for the 21st century.

The Liberal Party’s approach to policy, politics and philosophy across the past decade has been at odds with the seismic post-liberal realignment in Western democracies about the role of government and the importance of civil society and community.

Following several economic crises, the Covid-19 pandemic, disenchantment with globalisation and declining living standards, and a discomfort with the atomisation of society, Australians rightly expected their governments to care for them and to be a strong, active and constructive force in society.

The Liberal Party’s brand of values-free market liberalism and anti-government conservatism was not adapted to the times and did not resonate with the Australian ethic.

Too often while in government and opposition, the moderate liberals espoused a hollow “zombie Reaganist” approach to economic and social policy, privileging the free market and the interests of boomers above addressing the housing affordability concerns of young people, tackling inequality and cost-of-living pressures, and fighting for manufacturing industries.

At the same time, the conservatives became associated with cruel immigration policies (even US president Donald Trump thought our border policies were harsh), relentless and insensitive culture war rhetoric on social issues and a reflexive opposition to meaningfully including Aboriginal people in Australia’s constitutional compact.

Australian conservatism is fundamentally distinct from its North Atlantic counterparts. The body politic was never formed in the rebellious fervour and anti-government sentiments of the American or French revolutions. The crown and executive have largely been regarded as a responsible and constructive presence in Australian political life – a “helper, not an oppressor”, as barrister and writer Gray Connolly framed it. At its best, Australian conservatism is pragmatic and community oriented, more concerned with looking through the front windscreen than about what’s in the rear-view mirror.

To this end, the Liberal Party needs to reform its right flank into a contemporary, compassionate conservatism, devoted to fostering the common good and Australian national interest through universal human values such as family, community, security and dignity. This aligns with Menzies’ iconographic “Forgotten People” speech of 1942 and its support for “homes material, homes human and homes spiritual”. Despite contestation over the naming of the Liberal Party and the nature of its core ethos, Menzies undoubtedly had strong conservative instincts and policies.

To become electorally viable, the conservative flank of the Liberal Party cannot afford to descend into a reactionary conservative movement, dedicated to taking Australia “back down the time tunnel to the future”, as Paul Keating once joked of Howard. Nor can it drift into MAGA-lite populism, with all the ugliness, polarisation and isolationism of the grievance-driven right that has emerged in the US.

It also must reject the ideological anti-government strain that has undermined the party across the past decade. Australians value effective, well-run public services. The party should be pro-good government, not anti-government.

The Liberal Party’s fundamental purpose should be to protect and advance the dignity, security and opportunity of every individual and community across Australia.

In broad strokes, this nation-building compassionate conservative and community-focused liberal vision can be realised by:

● Ensuring home ownership and liveability are central to the Liberal Party’s ethos. Young people will not vote for a conservative party if they have nothing of their own to conserve. Embark on bold supply-side reforms, connect urban centres to major cities with high-speed rail funded through land value capture uplift, and wield the commonwealth’s legal and financial powers over the states to incentivise homebuilding for the good of the body politic.

● Making Australia a technology-neutral energy superpower. Develop a pragmatic mix of strategic renewables, gas and nuclear energy to secure reliable, scalable and low-emissions baseload power to meet Australia’s energy and industrial needs while ending outdated restrictions on nuclear and gas exploration and development to support the energy transition. We should be as wealthy as the Gulf states with our mineral and energy reserves.

● Growing and diversifying the economy to benefit all Australians. Australian living standards are declining the fastest in the OECD and we rank 105th in the world for economic complexity. Bold economic reforms are needed to increase aspiration and opportunity: index income tax brackets; increase productivity through skills, technology and AI; reduce regulatory burdens on small and medium businesses; curb unsustainable spending to reduce inflation, debt and deficit; and rebalance the economy’s dependence on government spending in favour of private enterprise. Economic growth is necessary to ensure the sustainability of our generous social services.

● Strengthening national security and resilience. Recalibrate and increase defence spending to improve the sovereignty and lethality of our armed forces; build supply chain and fuel security; and establish a voluntary national service program to address the ADF’s recruitment and retention issues and support natural disaster resilience organisations.

● Managing responsible and nation-building immigration. Ensure immigration serves a nation-building purpose; that is, filling genuine skills shortages, developing the regions and encouraging innovation; that it does not overwhelm housing and infrastructure capacity; that there are civic integration initiatives such as English language programs and community supports to foster social cohesion; and maintain a generous refugee and humanitarian program.

●Advancing reconciliation with Indigenous Australia. Meaningful, realistic and safe constitutional reform is critical to strengthen our shared nationhood, uphold the “honour of the crown” owed to Indigenous peoples and to promote Aboriginal-led approaches to close the gap.

● Ending the grievance politics and rhetoric. Foster a politics of respect and dignity, and encourage inclusive engagement with all Australians, especially vulnerable groups. How the Liberal Party speaks to Australians matters, almost as much as the substance of its policies. Disagree with the left where necessary, but appropriating the language of the US’s culture war rhetoric and its “war on woke” doesn’t work in Australia.

The Liberal Party struggled for traction on each of these major issues at the election, where Labor is nonetheless vulnerable and doesn’t have realistic solutions to the nation’s problems. Failure to address these challenges has fuelled political fragmentation and polarisation in Britain, Europe and the US.

The intellectual and policy foundations of “the broad church” will need to be rebuilt to win government and meet these national challenges.

To do so, the new Liberal leadership will have to find a new equilibrium for its liberal and conservative wings centred on compassionate conservatism and community-focused liberalism, fashion a kinder political movement, and reconnect with urban Australia, women and multicultural communities.

Whether Sussan Ley and Ted O’Brien are up to the challenge remains to be seen.

Nick Fabbri is a Sydney-based policy analyst, writer, podcaster and army reservist

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout