The depth of the Liberal Party crisis was not invented over the past month. It has been years in the making – directly traceable to 2015 and 2016 and going back even further. The party was put on notice with the 2022 election defeat and what did it do? Next to nothing, taking refuge in denial.

The party failed to act after the devastating 2022 campaign review conducted by Brian Loughnane and Jane Hume, and there are real fears the Liberals will fall short again. Political parties are tribal beasts, living by their tribal faiths and rituals. It takes a wrench to reset. Whatever the Liberals decide, they should begin with a clean slate – everything must be on the table.

The reason the Liberal Party was broken in election 2025 was because too many Australians no longer knew what the Liberals stood for and too many who did know were no longer persuaded. The Liberal Party needs an imaginative reconception.

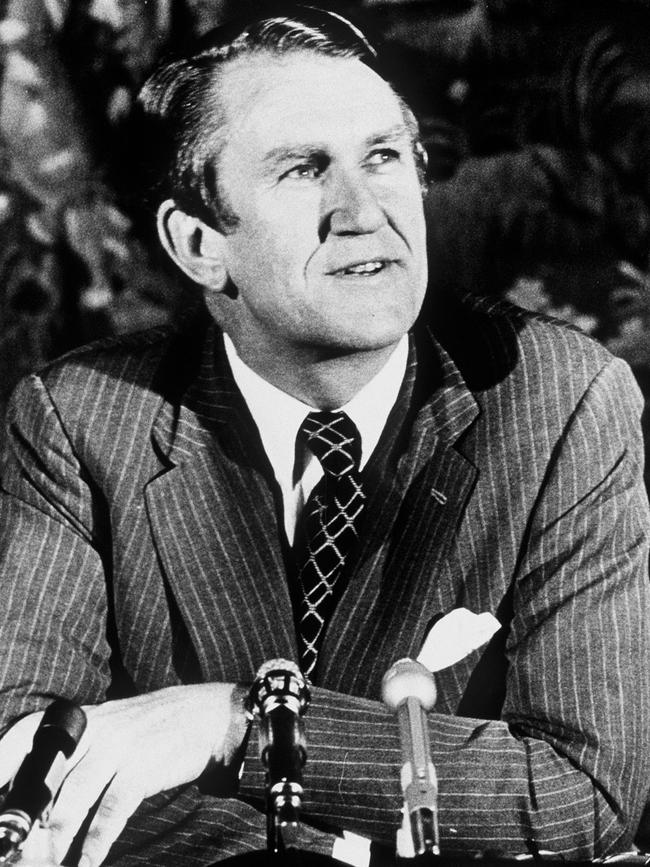

Malcolm Fraser and John Howard – the two longest serving Liberal prime ministers after Robert Menzies – reinterpreted Liberal values and policies for their own times. They invoked Menzies but rewrote Menzies. That’s what successful leaders do. That task is now greater than ever because the party faces a crisis of identity, organisation, philosophy and policy.

The lesson of election 2025 is that the public will endorse a lacklustre Labor government if the alternative is weak and unconvincing. The Liberals cannot win on Labor’s mistakes; they need to win on their values and policies. Integral to this task is repairing their ties to four pivotal centres of Australian life – the managerial and professional class, women, younger voters under 40 and ethnic communities.

In truth, too many Liberals are alienated and uncomfortable with too many centres of contemporary Australian life. The Liberals are experts at criticising what’s wrong with Australia but inept in sorting out any solution. Often they lack the language and cultural ability to explain themselves and their values to their fellow Australians. The country is changing around them.

This election has altered the structure of Australian politics. It will deliver another two terms of Labor government – making nine years in total – but when the inevitable swing against Labor arrives it won’t guarantee a Coalition government with, at that point, a minority ALP government being a distinct possibility.

The chief defect in the Liberal 2025 campaign was lack of conviction. Peter Dutton ran a campaign of extraordinary caution (nuclear power aside). It was narrowcast, focused on a flawed cost-of-living effort such that, in branding terms, the Liberal identity virtually equated with cheaper petrol. Full stop. That retail pitch would work only if encased in a values branding – and that never happened.

The Liberals were frightened of Labor. They matched most of Labor’s spending; refused to embrace tax reform and backed tax rises instead; shunned industrial relations reform; delivered a budget bottom line with higher deficits than Labor for the next two years; delayed their higher-spending defence policy until people were voting; failed to explain how they would deliver cheaper power; rarely discussed economic management; and shunned any cultural issues – most conspicuously an education policy to tackle declining school performance.

Leadership is more vital than ever in Australia’s presidential-style politics. Anthony Albanese not only outpointed Dutton at that level. Labor has a proven model of personal targeting of Liberal leaders – destroying them on character grounds – with its cultural messages taken up by progressive media, educational and cultural influencers.

It happened with Scott Morrison; it was repeated with Dutton. Yet the Liberals seem devoid of any retaliatory strategy to a Labor method now decisive in election outcomes. This doesn’t deny the limitations of Morrison and Dutton – but it highlights the fact by election day neither Liberal leader was actually electable.

The 2025 Liberal campaign was one of its worst. But historical context is essential to grasp what happened. At the last four federal elections the aberrant result was 2019 when Morrison defeated Bill Shorten, just. In the other three elections – 2016, 2022 and 2025 – the Liberals were outsmarted, out-campaigned and suffered numerous losses, with Malcolm Turnbull just falling over the line in 2016, Morrison suffering the worst defeat in Liberal history in 2022, only to be exceeded by Dutton in 2025 suffering an even worse defeat.

At each election the same defects were on display: weak projection of Liberal values, unappealing policies, poor on-the-ground organisation, an inability to counter fierce Labor negative campaigns, repeated Labor messages the Liberals were risks to Medicare, and a deepening sense the Liberals were out of touch with contemporary Australia. The Liberals kept fooling themselves the worst wasn’t happening. The traps were Morrison’s 2019 election win and Dutton’s 2023 referendum victory on the voice.

These were wins against the trend. During the recent campaign I wrote the danger for the Liberals was that 2025 would repeat the 2022 defeat. I got that wrong – it was far worse.

It will take a long time, post-election, to sort the future direction. There are two catastrophic factional pathways to be avoided.

The first is the idea the Liberals weren’t conservative enough at this election and the party must embrace the populist pro-Trump right, lean into aggressive conservatism and lurch further to the right, the sort of view favoured by the populist right-wing media.

This proposition is based on a misreading of Australia’s character and history and betrays the foundational principles of the Liberal Party. If followed, it would terminate the Liberals as a governing party.

From the inception of European politics on this continent with the arrival of the British in 1788 Australia has never been a majority conservative nation. It never will be. There is no national party called conservative for good reason. There have been three great political traditions in this country – liberalism, social democracy (or socialism) and conservatism. The latter is the weakest.

That the Liberal Party might decide 80 years after Menzies formed and named the Liberal Party that it was essentially a conservative party would be an act of political self-destruction.

The second blunder would be to decide the Liberal Party had to engage in a half-hearted embrace of left progressivism as its salvation mantra to win back women, the youth vote and the teal seats. This is tantamount to political surrender on the terms dictated by your opponents.

It would mean the abandonment of Liberal values as well as liberalism’s values; a deliberate realignment to the left; a degree of acceptance of progressive views on identity contrary to the party’s success in defeating the voice referendum; embracing much of the progressive critique of the Western cultural tradition; and accommodating, post-Covid, the rise of government paternalism, higher government spending and growing state power in most aspects of life and social control edicts.

Any such option would shatter the unity of the Liberal Party, betray its principles and guarantee a fracture from the conservative wing. Again, it would be fatal for the party.

The best framing for the future is the Howard concept of a “broad church”. That broad church is now in ruins. But its revival is the only viable strategy because it opens the lens wide, it is inclusive, it incorporates both the liberal and conservative traditions, it offers a broad basis for public policy and a welcoming window for a wide range of Australians. It would open the party to the country, not shut its doors.

This doesn’t mean Howard revisited; it means reinterpreting the “broad church” for the 2020s. The risk now is a factional conflict between conservatives and so-called moderates on the party’s future.

Howard knew the “broad church” concept was the key to internal unity and winning elections. If today’s Liberals have any hope for their future, they need to understand and take the best from their past. Or will a beaten party now devour itself?