Legend of thebaggy green

Not everything seen in the Australian cricket cap is as it seems: indeed, most common assumptions nurtured about it are erroneous.

To solve the mystery of the “blue carbuncle”, Sherlock Holmes has a solitary clue: an old trilby hat recovered from an affray. He encourages Dr Watson to look upon it as an embodiment of the wearer. “What can you gather from this battered old felt?” protests his friend. ‘”I can see nothing.” The great detective reassures him: “On the contrary Watson, you can see everything.”

Not everything seen in the Australian cricket cap is as it seems: indeed, most common assumptions nurtured about it are erroneous. It is far from eternally unchanging, having been extensively modified over time. It has not always been baggy or even green; the Australian coat of arms it features is redundant. Even the phrase “baggy green cap” is of relatively recent usage, while its presentation to newly minted international players was not ritualised until the late 1990s; indeed, it used to be distributed quite liberally to players on non-Test match occasions. In short, we are moving in the realm of Eric Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented tradition”.

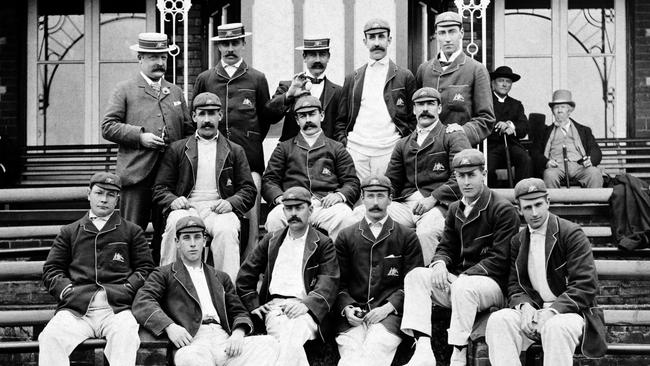

The first Australian cricketers to tour England, the Indigenous team of 1868, took the field resplendent in a uniform of white trousers and maroon shirt with a cream sash. Dave Gregory’s team a decade later wore a blazer of white and azure blue stripes, topped with a matching brimless cap. A peaked cap had come into vogue by the time Billy Murdoch’s team toured again in 1880, playing Australia’s first Test in England, but this time in magenta and black. When Australia won the Test that inaugurated the Ashes tradition at the Oval in August 1882, it bore the colours of the Sydney-based 96th Regiment: red, black and yellow.

If Australian cricket had a colour at all in the first quarter century of international competition, it was blue. Murdoch’s 1884 Australian team wore a fetching navy jacket with gold piping. The team that toured two years later were blazered in blue, red and white: the colours of the Melbourne Cricket Club who were the tour’s organisers and underwriters. In Australia there was not even this level of cohesion. Teams played in the colours of the colonial association hosting the match, a reflection of the fact that the local body was also responsible for selecting, marshalling, accommodating and paying the team.

Australia’s 1893 tour of England was the first under the auspices of a national organising body, the fledgling Australasian Cricket Council, and the team’s blue caps and blazer bore a shield-shaped patch enclosing the stars of the Southern Cross in a cross of St George, beneath which was the legend “Advance Australia” – a sentiment at least 70 years old. It did not have the desired inspirational effect on the players. “It was impossible to keep some of them straight,” complained the team’s manager, Victor Cohen. “One of them was altogether useless because of his drinking propensities.”

Green and gold’s sudden primacy is mysterious. Initially it found no favour: at a meeting of the council in Adelaide in January 1895, the motion that “the Australian XI’s colours be olive green with the Australian coat of arms worked into the cap and coat pocket” lapsed without a seconder; three years later, “a very attractive arrangement of green and gold colours” was suggested, only for the council to collapse soon after.

When Australia’s 1899 tour of England came to be arranged, however, its backers, the Melbourne Cricket Club, adopted the colour scheme out of sensitivity to whispered criticisms that the institution was too rich and influential in the local game. The team on arrival outfitted itself in blazers and caps of “sage green and gold”, and hoisted a green and gold flag above their headquarters at Holborn’s Inns of Court Hotel. Had Australia lost the series, the colours might never have caught on; as it was, success against strong opposition on this and the imminence of federation lent them totemic qualities. Cricketers are superstitious; they stick to teams, routines and gear that they associate with success.

When the state associations regathered their forces to originate the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket in May 1905, they regained control of the uniform. Somehow, it escaped the board’s attention that a new Australian coat of arms came into being in 1912, so the Australian cap continued to bear the symbol that had officially been retired. The legend “Advance Australia” was finally replaced by “Australia” 20 years later.

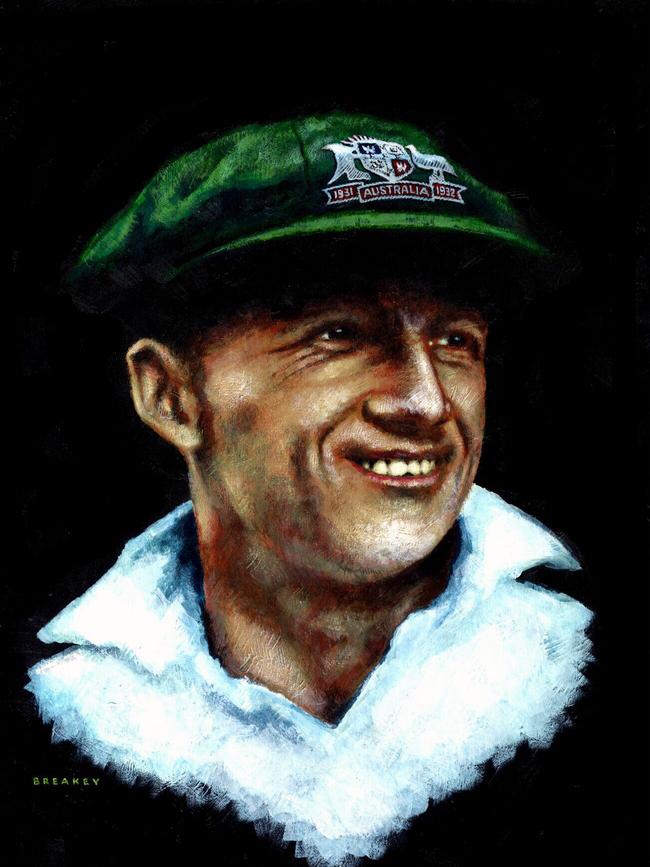

Australian cricket administrators took a long time to realise the value locked up in their national cap. Until the 1970s, “baggy green” was associated with camouflage. Journalists tended the lore. “Under their green caps, their forces have been harder to repel than the Spanish armada,” said Ray Robinson in his canonical On Top Down Under (1975). The era was celebrated in Ian Brayshaw’s Warriors in Baggy Green Caps (1983).

Kerry Packer deferred to it, having the Australians who appeared in his breakaway World Series Cricket troupe between 1977 and 1979 play in tight-fitting yellow caps. When his general manager suggested the use of green headgear, Packer snapped: “You’ve got to earn those, son.”

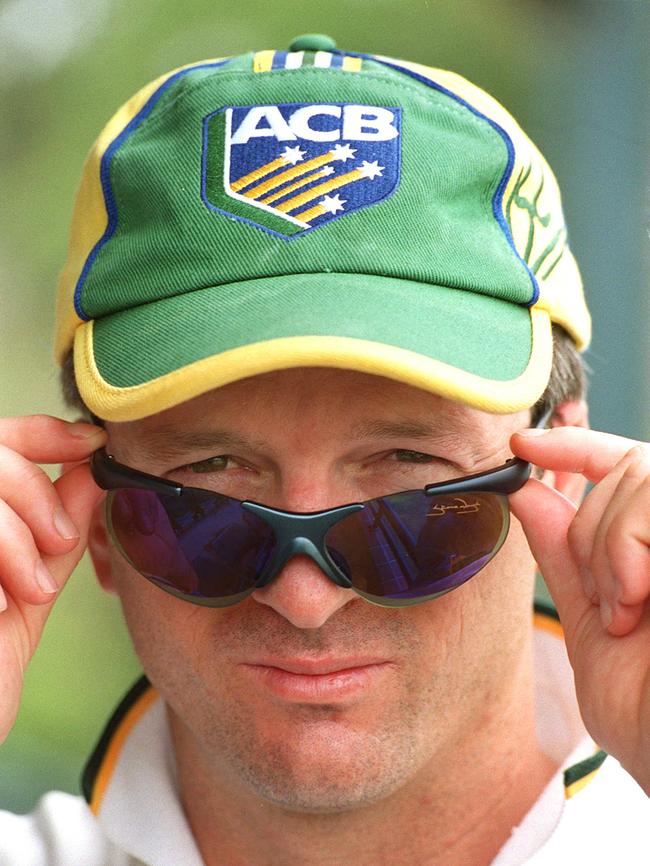

If any individual is responsible for the cap’s latter-day iconic status it is Steve Waugh: its ultimate elevation to a national symbol dates from his captaincy. Quite why is almost worthy of psychoanalytic scrutiny, although at one level it is probably as simple as Trumper’s attachment to his cap: he made runs and won games wearing it. Like Trumper, Waugh was a superstitious cricketer, who never played without his lucky red rag; the cap, likewise, became part of his psychological armour.

Others concurred. After Australia’s victory in the Worrell Trophy in May 1995, for example, Waugh noted the conspicuousness of the cap in the dressing room celebrations: “Lang (Justin Langer) retained that Australian flag draped over his shoulders all night while Heals (Ian Healy), Slats (Michael Slater), Lang and I kept the baggy green on until we were told the festivities were over.”

Respect for an imagined past became a motif of Waugh’s captaincy when he assumed the role in February 1999. He inaugurated the custom of Test debutants being presented with their caps by a distinguished ex-player; he commissioned replicas of the turn-of-the-century Australian cap to be worn in the Sydney Test of January 2000; he led the team on a pilgrimage to Gallipoli in May 2001 en route to England, inspired by a conversation with Lieutenant General Peter Cosgrove in which they “compared cricket and the army, especially things that are important in both endeavours – such as camaraderie, discipline, commitment and the importance of a plan”.

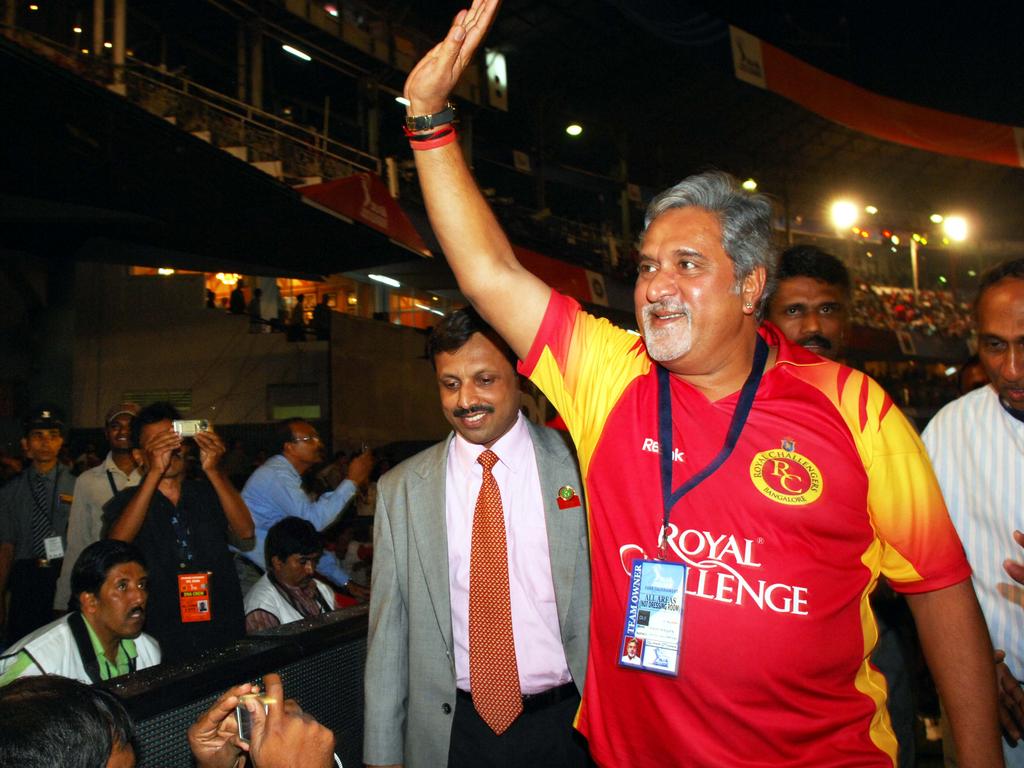

The baggy green was a brand name ripe for celebration, precisely because it had been so relatively little exploited before. The board had always received legal advice that the Australian Trade Marks Office would not consent to trademark protection for an item involving a coat of arms. But various annoyances – including an advertisement by the brewer Coopers Brewing Company in which baggy green caps replaced the lids on stubbies – led to chairman Denis Rogers approaching the devoutly cricket-loving prime minister John Howard. A legal adviser to the Prime Minister’s Department helped the board prepare registrations across several trademark categories, which were then expeditiously approved.

Thus did the baggy green become an asset beyond value in the board balance sheet, advertised by the launch of the official Australian cricket website, www.baggygreen.com.au (run by Channel 9), and tapped by licensed merchandise. Its History of the Baggy Green was marketed as the “consummate Australian cricket collectable, taking you through an authoritive (sic) journey exploring the history, tradition and pride of the coveted baggy green” and featured “an actual green flannel swatch as used ... in the crafting of the baggy green”. To protect what was now a commercial asset, the board restricted the production and distribution of the baggy green more than it had ever done before. As the national women’s cricket team became increasingly professionalised, its players too embraced the baggy green, although there is some lingering resentment that its badge remains subtly different from the men’s.

A number of reasons can be advanced for the baggy green exhibitionism around the turn of the millennium – a hankering for continuity in a period of change, the recrudescence of Australian conservatism, the desire for values transcending the shallow materialism of modern sport. But one factor shouldn’t be overlooked: no stakeholder did it not suit. Players building private esprit de corps and public reputations, administrators striving to generate brand value and to control intellectual property, broadcasters trying to engender viewer loyalty, sponsors anxious to identify with a premium product, fans and sports journalists seeking symbolic embodiment of their allegiance.

The attachment of that last group, however, involves some unexamined assumptions. It is commonly repeated that the baggy green is essentially held in trust for the public of whom the Australian team are representative. Waugh did not feel that way: “The players ‘own’ the Australian team traditions and to be able to partake of these rituals and traditions has meant you have been awarded the highest honour in Australian cricket – you have been selected to play for your country.”

In other words, it was the current players who defined the baggy green, not the public, and as its “owners” they defined appropriate behaviour. For instance, when ex-players criticised the methods of former Australian coach John Buchanan in December 2007, Adam Gilchrist jumped to his defence: “I guess one of the traits that we have a lot of pride in, in wearing the baggy green, is that we show a lot of respect. It seems some guys in retirement have lost that ... (The Australian team) is an elite club and we’ve always felt a major characteristic of being in that club is to show respect.”

In an allegedly egalitarian country, this could be seen as a strangely inegalitarian remark, an assertion of caste and status, a claim to be beyond criticism. When Steve Smith, David Warner and Cameron Bancroft were arraigned in March 2018 on charges of aiding and abetting ball tampering in a Test in Cape Town, it shattered the players’ claim that they could define appropriate behaviour and the public issued a stern verdict: “Not in our name.”

Smith and Bancroft wore their caps to the press conference where their equivocations and evasions deepened their plight; their caps accentuated their disgrace. All three were unceremoniously stripped of their uniforms before returning home to lengthy suspensions. Part of the restoration of Australia’s fortunes and reputation was a new coach, Justin Langer, who employed his old mucker Steve Waugh as a muse and guru during the 2019 Ashes.

The cap’s redemptive powers were put to a further test in January 2020 when, in the aftermath of the summer’s calamitous bushfires, fundraising initiatives included the auction of the baggy green owned by Shane Warne. Warne had been a noted agnostic where the cap’s properties were concerned (“There was too much verbal diarrhoea about the baggy cap, it was a bit too over the top for me”) but grasped its magic in the eyes of others.

The purchaser, for a record $1,007,500, was another Australian icon: Commonwealth Bank. Reputation tarnished by the Hayne Royal Commission into the banking industry, which had resulted in the departure of its CEO, the bank was seeking the burnish of sporting and charitable associations – it announced plans for the cap to go on display at Bowral’s Bradman Museum. Sherlock Holmes was right. About the headgear’s new owner you could tell a lot.

This is an edited extract from Symbols of Australia: Imagining a Nation published by NewSouth. Out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout