Cricket’s headlong rush towards privatisation

The commitment of $2.13 billion to new IPL franchises in Ahmedabad and Lucknow will ramify round the world.

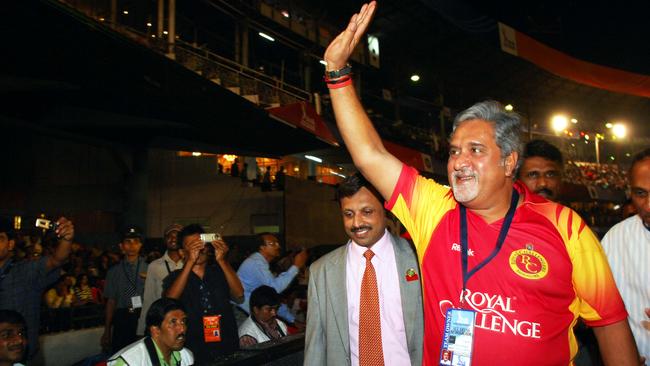

Limousines decanted Bollywood stars in oversized sunglasses. Vijay Mallya, the self-styled “king of good times” who is today a bankrupt fugitive, arrived in a red Bentley, and left with Royal Challengers Bangalore. Other investors included Modi’s brother-in-law and the secretary of the Board of Control for Cricket in India.

Last week’s sale of two new franchises struck a different note: a dry, private, six-hour affair in Mumbai involving an elite of nine leading corporate names whittled from 22, including the Glazers, Manchester United’s owners, and Adani Group, whose success would have tested Australian cricketers’ new climate consciousness.

In media here, it barely merited a line. But the commitment of $2.13 billion to franchises in Ahmedabad and Lucknow by, respectively, CVC Capital Partners and RP Sanjiv Goenka Group, will ramify round the world.

Why? The expansion of the IPL from eight teams to 10 involves an extension of the tournament from 60 games to 74 — something long in prospect, as little economic sense is served in clubs being active only two months in 12, but further depleting the breathing space in a cricket calendar also set to be squeezed by an International Cricket Council event every year.

The BCCI, with its ever-expanding T20 money-spinner, is now effectively in competition with the global body, of which it is the largest member, for talent, dates, television and sponsorship monies.

The rights to the IPL and the rights to ICC global events, both currently with Star, are set for sale again in the next year. A dollar allocated to one is a dollar unavailable to the other.

The tighter squeeze, however, will be suffered by bilateral cricket, and especially Test cricket, which apart from a couple of marquee series effectively runs at a loss.

The franchise auctions also marked another milestone on the approach to a budding debate, here and elsewhere, about private ownership in cricket — a step that Manoj Badale, one of the original investors in the Rajasthan Royals, argues is inevitable.

“It is not a question of either/or, but a question of how and when,” says Badale in his recent book A New Innings (2020).

How was once a simple affair. The oldest model, still popular, has been sport as a luxury appurtenance: 62 of the world’s billionaires own sporting teams.

For the first generation of owners in the IPL, cricket was mainly a fun thing to be associated with that might have some branding opportunities.

Thus Chennai Super Kings, named by owner India Cements for its premium brand; thus Kolkata Knight Riders, a billboard for its actor cum mogul proprietor Shah Rukh Khan.

Beyond the League they did not look far, save in the direction of the Caribbean Premier League, where Badale’s Emerging Media now controls Barbados Royals, Punjab Kings shares owners with the St Lucia Kings and Kolkata Knight Riders with the Trinbago Knight Riders.

Now comes venture capitalists such as CVC who embody the transfiguration of sport into business. Their new franchise will be in the heart of the capitalist playground of Gujarat. They have invested heavily in international rugby union and association football, including, controversially, La Liga.

CVC’s sports investments, moreover, coexist cosily with extensive gaming and betting activities [dash] which makes it a … errr ….colourful new addition to a league that has had its probity problems in a country where gambling is effectively illegal.

CVC also have an outpost in Sydney, and will be among those scouting Australian sporting assets. Rival Silver Lake is already making its presence felt, being reportedly on the brink of investment in the A-League.

Cricket Australia wants to be ready, having sidled up to then shied away from private investment at the inception of the Big Bash League — GMR, owner of what was then the Delhi Daredevils, had their foot on a minority stake in a BBL club 10 years ago, only to be told it was not for sale.

Some now view private investment as the solution to a capital constrained world, weaning the game off its dependence on broadcast rights whose growth is tapering. The England Cricket Board will almost certainly seek to recoup the start-up costs of The Hundred by flogging its mushroom teams in the next few years.

The next CA strategic plan, being prepared in consultation with Boston Consulting Group and due for release mid-2022, is set to traverse private ownership in relation to the BBL, whether it is auctioning individual franchises or a portion of the competition itself.

There are some interesting arguments here. There’s no doubt that private investment has revolutionised Indian cricket, never more innovative, accessible or prosperous. The BCCI could never have achieved its current status of global hegemon under its own motive power alone.

But there are good reasons cricket has hastened slowly in these parts, and they still pertain. We can divide them, broadly, into three.

Firstly, CA would inevitably erode the idea of its public custodianship of the game, from which it derives privileges such as its exemption from tax and its identification with the nation.

The balance between long-term value and short-term profit would be disturbed, and even the license to be righteous curbed. Imagine trying to espouse gender equality having welcomed Saudi cash, as the English Premier League just has at Newcastle United.

Second, CA would face an enormous challenge in distributing such money as it realised. It was the prospect of private ownership a decade ago that drove governance reform, because the old representative board faced irreducible conflicts of fiduciary duty in deliberating on the issue.

The prospect did not eventuate, the reform ended in a halfway house of independent directors nominated by members, and recent experience suggests that the states differ on as much as they share. Throw money into the mix and … stand well back.

Thirdly, CA would be running the gauntlet of public ambivalence about commerce’s influence on sport, which this year, notably in the European Super League, flared into outright hostility.

A proportion of fans already complain that cricket is a business; private capital’s encroachments would affirm existing misgivings.

Cricket followers might learn to abide it, as have fans of the NRL, NBL and A-League; the effect might be mitigated in the event of its limitation to the BBL. But private ownership in Australian sport, perhaps a little unfairly, remains more associated with excesses than successes.

It may in the end depend on how you feel about billions of dollars changing hands in the context of what is, after all, a game: easy or queasy.

When the Indian Premier League’s founder Lalit Modi sold its first eight franchises in January 2008, the occasion was gaudy and incestuous.