‘Land of newspapers’: The Australian evolution

Rupert Murdoch’s first national daily upholds a time-honoured mission even as it meets modern challenges.

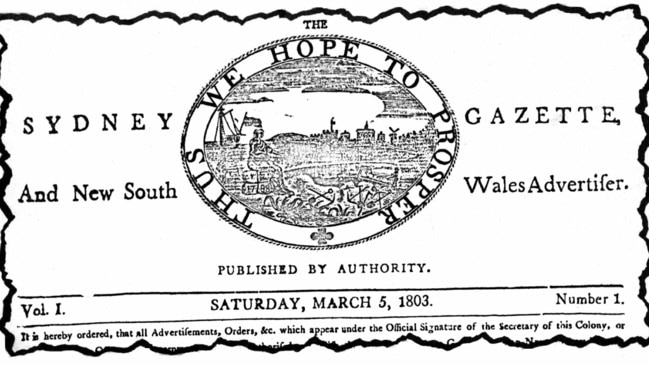

“Thus We Hope To Prosper”, announced The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, the first newspaper published in Australia, on Saturday, March 5, 1803.

Edited, typeset and printed by convict George Howe, its moniker was emblazoned around a masthead image of progress: a windmill and a man at plough denoting agriculture, buildings and towers suggesting civilised town life. The paper’s slogan could have been referring to itself as much as the scene it depicted – innovation, enterprise and an informed public being the keys to the prosperity the new settler society sought to cultivate.

A little more than 220 years later, in the wake of the 60th birthday of The Australian, the motto and the assumptions underpinning it seem more apposite than ever.

The second part of the Gazette’s name was as significant as the first. Unlike many newspapers of the period, the Gazette looked to advertising, not a restricted subscription list, for its income. Its first issue contained advertisements for a sale of recently arrived cargo – tea, table rice, “soft sugar of a very fine quality” and European soap; chintz for curtains and upholstery; handkerchiefs, frocks, soldiers’ plain and frilled shirts. No penal gulag, Sydney was already a flourishing maritime entrepot, a free colony with a free market, where even convicts could work in their free time, earn money and run businesses.

The Gazette came into existence for the same reason as The Australian. There was a market for it, and a need. Newspapers are emblematic of modernity. The “new” in “newspaper” underscores the point. A defining feature of modernity is that things are always changing and happening. It’s governed by the sense that the latest information – the newest knowledge of events taking place right now – is the most valuable.

Nowhere was the sense of newness more pronounced than in the recently founded colony. For the settlers everything was new, from the regulations under which they lived to the opportunities they hoped to exploit. Finding their way required information – and the demand for information was heightened by the hankering for news from home. Newspapers were as much tools of acclimatisation as hoes and rakes. Their beginning, however, was “Under Authority”. Published with the governor’s official sanction, the Gazette’s contents were carefully supervised. The shackles were soon shirked off.

In June 1824 – just on 200 years ago – the first newspaper free of government censorship was published in Hobart. By the end of the decade, newspapers in NSW and Van Diemen’s Land had ceased to be censored. Remarkably for a convict colony, they operated with a freedom unknown in Britain.

There, effective censorship continued through registration fees. Readership circulation was contracted into a small inner circle through heavy stamp and advertising duties, taxes on carriage and distribution, and on the paper itself.

Those restrictions – the despised “taxes on knowledge” – had the perverse effect of encouraging a radical, unstamped “pauper press” that was deeply hostile to the prevailing order. Cheap to make, distributed locally and unofficially, the unstamped press had no incentive to appeal to mainstream opinion. Meanwhile, the established papers, led by The Times, catered exclusively to the social elite

In Australia, that divide didn’t exist. From the Gazette’s very first issue, newspaper proprietors relied on advertising for revenue and so sought as wide a readership as possible. Revolutionary politics didn’t feature – although campaigns of abuse against the governor quickly became a hardy colonial staple.

The more autocratic governors (Ralph Darling in NSW, George Arthur in Van Dieman’s Land) tried to impose constraints. The genie of press freedom, they soon learned, couldn’t be jammed back into the bottle.

Australian governors complained that the editors and proprietors were dangerous radicals, but the likes of William Wentworth, Robert Wardell and Edward Hall (barristers, bankers, large landholders) weren’t even on the same street as their unstamped London counterparts. They may have stridently denounced government excesses, but their commercial survival depended on reflecting, if not shaping, the attitudes and aspirations common to the wider population.

The gold rushes that began in 1851 gave that role unparalleled importance. The sudden quadrupling of the colonial population vastly boosted the potential market, while the arrival of the first industrial printing presses, with their high fixed costs, made it vital for papers to achieve economies of scale.

Moreover, the settlers who flocked to the booming colonies were the first majority-literate generation in modern history. Arriving in a new society, hungry for every scrap of information, they were ideal newspaper readers.

New countries fostered the craving for latest news, reckoned Englishman Richard Twopeny. In the 1880s he christened colonial Australia “the land of newspapers”.

The journalist, editor and entrepreneur found the Australian colonist “an inquisitive animal, who likes to know what is going on around him”. Australia’s early uptake of mass education, in conjunction with short working hours and high wages, meant “nearly everybody can read, and nearly everybody has leisure to do so”. The proportion of the population who purchased newspapers was, thought Twopeny, “10 times as large as in England” and almost certainly the highest in the world.

Just as significant as the arrival of gold rush settlers and mass-produced newspapers was the simultaneous achievement in the 1850s of effectively universal male suffrage. Until then, newspapers had helped form settlers; now they forged citizens. Carrying reports from stormy public meetings and parliamentary debates, they knew most of their readers were passionately interested in the latest controversies.

The newspapers shaped the new democracy in a way unlike anywhere else. In contrast to the US and Britain, where party politics established itself in advance of mass newspapers, here newspapers drove political campaigns, organised constituencies and themselves helped engender the party politics of mass democracy.

Without major institutional parties to structure political conflict, politics coalesced around single issues. Launching public campaigns on those issues, newspapers became fulcrums of political power, building influence and readership along the way.

In 1850 Henry Parkes’s Empire newspaper began its – and Parkes’s – great political career forcefully advocating for the Anti-Transportation League. Equally, the Melbourne Argus vaulted to public relevance in the early 1850s when its owner, Edmund Wilson, started campaigning to confiscate large pastoral leases from “squatter” graziers and make them available for the new arrivals. It was the first iteration of a campaign that transformed colonial land ownership and rural Australia with it.

While that was happening, David Syme took over the running of The Age after its owner, his brother Ebenezer, died in 1860. Coming relatively late to campaigning politics, Syme compensated for lost time, embracing tariff protection. Syme and The Age were arguably the most significant factor in making protection a hallmark of Victorian liberalism and, after Federation, a defining part of the Australian Settlement.

In short, mass politics and mass circulation newspapers were the nativity of Australian party politics, not the other way around, as in Britain and the US. It is therefore no accident that so many of the major political leaders of this period – including Parkes and Alfred Deakin – began their public lives in the press.

The role of newspapers as forgers of citizens became even more pronounced as the 19th century merged into the 20th. Once again, that partly reflected technological developments. Newspaper-printing machines that could print tens of thousands of issues in an hour were among the marvels displayed at the Centenary Exhibition of 1888. Even costlier than their predecessors, they made securing vast print runs crucial.

Luckily, they became available just as the booming railway and construction industries created another emblematically Australian phenomenon – the suburbs.

Suburb dwellers were by definition commuters, travelling to and from work almost entirely on trains, trams and buses. As they travelled they read: first the morning paper, then its afternoon sibling. Train lines also allowed metropolitan papers to penetrate the country areas.

The big daily newspapers used their expensive printing machinery to churn out separate weekly papers – thick digests of news, sports, fashion and gossip – for the regions. These weeklies coexisted with country newspapers, of which every country town considered itself requisite to have at least one, preferably two, lobbing incendiary editorials at each other from across the street.

The collapse of the long colonial boom in the 1890s brought social tumult, but newspapers kept right on selling. The Great Strikes were defeated, and aggrieved unionists considered the game had been rigged against them: parliaments, the law and the newspapers had all opposed their militant campaigns.

Two immediate outcomes followed. One was the birth of the Australian Labor Party. The other, much less successful, was the establishment of Labor and union-controlled newspapers. Those newspapers struggled, but they proved an ideal nursery for some of Labor’s most substantial leaders. Jim Scullin, John Curtin and Ben Chifley all gained vital experience in union-controlled or Labor-friendly papers.

Newspapers were also central to the other great product of the 1890s bust: the Federation debate. Sydney’s towering Liberal newspaper, the free trade Daily Telegraph, was Federation’s implacable opponent. In Melbourne, heart of the Federation cause, Syme’s The Age was initially hostile. Syme was suspicious of any project that would dilute his all-pervasive influence in the colony: one in five Melburnians bought a copy of The Age each day, a preponderance unmatched by any other major metropolitan daily in the world.

However, once established, nationhood gave politics a new dimension. With the coverage of the first federal elections it became clear that newspapers were doing more than forming citizens – they were helping to define Australia and Australians.

That role reflected a stark reality: at the beginning of the 20th century, newspapers exercised an almost total ascendancy as sole purveyors of mass information. Dominance was short-lived. By the 1920s, challengers – cinema, radio – emerged. Thus began a process, which continues unabated to the present day, in which newspapers had to adapt to a rapidly evolving, ever more competitive media landscape. And adapt they did.

The increased “pictorial sense” that cinema watching encouraged was a case in point. Almost immediately, newspaper layouts responded to the public’s changed expectations. “News Pictorial” newspapers were established, privileging large pictures, banner headlines and much shorter news items instead of long text-based columns of newsprint.

Radio was an even more formidable challenger. Newspaper proprietors fended off its competition for as long as they could, ensuring that tight restrictions on the daily number and timing of news broadcasts were enforced.

But politicians ultimately got their revenge on editors and proprietors who they liked to insist were against them. When forced to resign as prime minister in 1941, Bob Menzies was inclined to blame the hostility of newspaper journalists and editors in general, and Warwick Fairfax of The Sydney Morning Herald in particular. By the time Menzies returned to power – at the head of a new party, the Liberals – in 1949, he had become significantly better at cultivating journalists and editors.

Yet the real way Menzies distinguished himself was in turning to radio. It is no accident that the most famous address in Liberal Party history, the Forgotten People speech of 1942, was delivered by Menzies as part of a regular series of radio broadcasts.

Creating a new form of intimacy between politicians and ordinary citizens, radio went directly into the domestic sphere, bypassing the street corner, workplace and town hall as the site of public politics. Bypassed, too, were newspaper editors and journalists.

The advent of television only heightened the challenge. Emblematic of post-war prosperity, its mass arrival coincided with the emergence of a more nationally integrated, more self-confident Australia in which national, rather than state, issues predominated. Australian newspapers were, however, state-based and state-centric, increasing their vulnerability to the new medium.

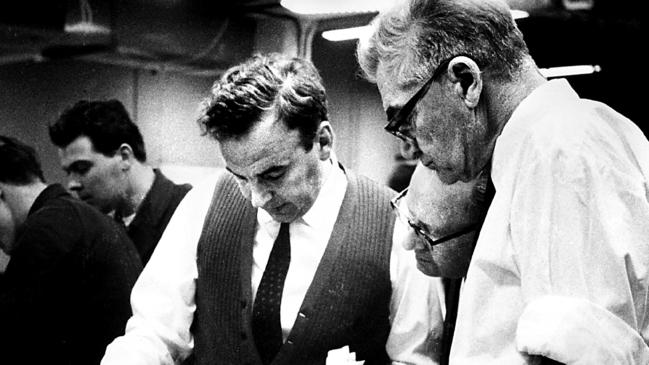

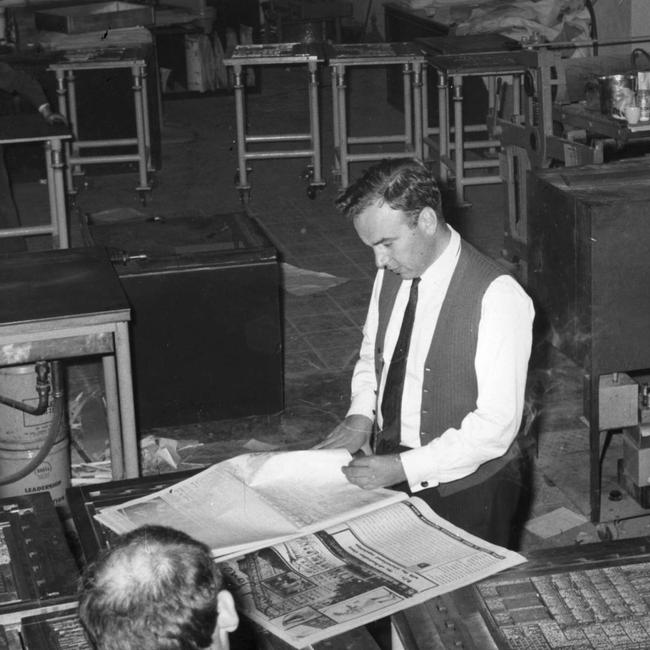

But a developing national orientation and a thrilling sense that Australia was coming of age were an even greater opportunity than they were a threat. It was that opportunity Rupert Murdoch seized when in July 1964 he launched the first national daily newspaper for general readers.

There were, when The Australian appeared, plenty of sceptics. Like the US, the sceptics argued, Australia was simply too large for a national paper. A newspaper for the whole country would be the equivalent, asserted one industry veteran, “of The Times in London being delivered in Moscow daily at breakfast time”. It wasn’t going to happen.

In the event, calculated risk and adaptation once again blazed the newspaper trail of national change.

Nowadays, the challenge lies in adjusting to the digital age – an age marked by a surfeit of information and a paucity of attention. Today’s online world is replicating the plethora of newsprint that followed on from the Gutenberg Revolution, when printed materials flooded the European continent. The nascent market for information was quickly debased. Much of supposedly factual accounts in “News Letters” and later “News Papers” was simply made up. States, too, began to use the new information technology to lie systematically. The result was decades of informational chaos. But chaos birthed order.

As the tohu-bohu of pamphlets, gazettes and chronicles – each more unreliable than its predecessors – created a demand for veracity, mastheads emerged, staking their reputation on accuracy. And as well as providing reliable news, they helped readers navigate the fog of debased information that obscured the contours of events. Curating what was worth knowing became the chief task of the first papers of record.

Those missions – timeliness, accuracy, curation – remain as important as ever. It is no doubt true that informational swamps, in which conspiracy theories and made-up “news” pullulate, will continue to infest the planet. So, too, will echo chambers where those who want their delusions confirmed will find exactly what they are looking for.

But that makes trusted mastheads only even more crucial. Among the millions of blogs and spurious news sites, they can continue to inform the public, shape the national debate and give this country its distinctive identity. Adapting as they always have, their pages – whether hard copy or virtual – will bring the world to new generations of readers; probing, provoking, explaining, as newspapers in this country have from their first steps to the present day.

The Australian, 60 years young, remains at the forefront of that proud tradition.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout