Labor’s challenge: Light on the hill flickers at dark time for democracy

Labor faces challenges on the road to renewal, domestically and in the face of a wider crisis.

When the Labor Party under Anthony Albanese returned to office federally in May 2022, it was in one sense a normal movement of the political cycle. A party out of office for nine years had returned, in a system that has provided for the alternation of Labor and a Coalition of Liberals and Nationals (and their predecessor parties) for generations.

Yet it also was clear that something had changed fundamentally. Labor won an election with less than a third of the primary vote. The Coalition fared little better. There was a crossbench of 16 independents and minor parties. If the so-called two-party system was not dead yet, neither did it appear in rude health.

Labor was in office for the 10th time since Federation, but it had been by far the less successful of the two sides competing for office since 1910. The party first gained national office 120 years ago this weekend, on April 27, 1904, at a time when such parties of the left in Europe were still far from power. John Christian Watson’s government lasted only four months but it was a foretaste of things to come.

When Labor won a majority for the first time in 1910, it seemed to have the country at its feet. But a split during WWI and the ordeals of the 1930s Depression set the pattern: Labor governments would be the exception rather than the rule.

Opponents of the party sometimes today ridicule it as a once-working-class organisation overtaken by “chardonnay socialists” or “latte sippers”. In reality, middle-class progressives have been a presence in the party since its inception.

Driven idealists of the working and middle classes have long seen the Labor Party as a means of achieving their goals; it also has served as a vehicle for obsessives, careerists and opportunists, as all political organisations do.

This century voters have dealt harshly with many of the political parties that the ALP might once have regarded as “fraternal”. Socialist and labour parties in France, Greece and Israel barely survive.

In Sweden, Norway and Denmark, the once-dominant parties of labour and social democracy now struggle in a much more competitive environment than last century.

That also has been the fate of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, the largest and most influential of the parties of the left during the era of the Second International grouping of socialist and labour parties before WWI. The defeat last year of parties of the centre left in Finland and New Zealand removed two governments that had been held up as beacons for modern social democracy. Each had been led by a popular and younger female politician, giving the impression of revival and renewal.

The Anna Karenina principle may well apply here. Happy social democratic parties are all alike; every unhappy social democratic party is unhappy in its own way. To what extent can the recent history of the ALP be seen as part of a wider context of social democracy in crisis?

One consistent thread is the decline of a working class rooted in easier to unionise and often geographically fixed workplaces, centred on manufacturing, mining and transport, and dominated by male workers, often with a high degree of ethnic homogeneity. Another argument in explanation for social democracy’s global decline is that the accommodations offered with capitalism by parties of the centre left from the 1980s helped them secure short-term success at the cost of a longer-term crisis of ideology, identity and purpose.

If this argument is valid, the story of Australian Labor should figure prominently in such an interpretation, since its embrace of market forces, however qualified by a continuing attachment to the social wage and support for the union movement, occurred as early as 1983, even arguably by 1975. It paved the way for similar parties in countries such as Britain and Germany to pursue Third Way policies in the 1990s.

Unprecedented federal electoral success between 1983 and 1996 would be followed by a period of more than a quarter of a century in which Labor tasted a meagre six years in office, three of them as a minority government, accompanied by a continuing sense of uncertainty about its core ideals and goals. The decline of Labor’s primary vote, as revealed so dramatically in 2022, reflected a wider loosening of political allegiance that affected both of the major sides of politics, but it arguably had more severe psychological, cultural and institutional consequences for a party whose identity had for so long been bound up in a sense that it represented the mass of “ordinary people” and offered voters a distinctive way of engaging with parliamentary democracy.

The global financial crisis had more muted effects in Australia than in most advanced capitalist countries, due to a mixture of good Labor economic management, formidable bureaucratic expertise and robust Chinese demand for commodities. And Australia’s federal system has provided opportunities for Labor at the state and territory level that it has readily taken up: even during dark days in federal politics, Labor’s electoral performances and policy achievements in the states and territories have been substantial.

Australia has experienced some anti-immigrant sentiment, but the political centre has held rather better than in Brexit Britain, Trump’s America or much of Europe. Right-wing populism of the Trumpian kind has been an influence, but a muted one.

All the same, it is hard to miss the role played by politicised national security policy, often entangled with the asylum-seeker issue, in weakening the ALP’s standing with many left-leaning and younger voters in the 21st century. The party’s disorientation over national security, and asylum-seeker policy in particular, helped defeat Labor in the 2001 election, did much to bring the Rudd and Gillard governments undone, and has contributed to the Greens’ electoral successes, which increasingly challenged the ALP in its old metropolitan heartlands.

Nonetheless, most notably in Victoria, now virtually a one-party state, across the past few decades Labor has arguably become the natural party of state and territory government.

From the early years down to the present, the ALP has attracted critics from both the left and right who have contested its claim to speak for the common people.

When the Albanese government came to office in May 2022, it was entirely predictable that within a short time it would be accused of doing too little, or acting too slowly, or being too much like its opponents. The passage of time lends an aura of romantic light to the past, but the governments of Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke attracted similar criticism, as has every other national Labor government. One book-length academic left-wing critique of the Whitlam government had the title From Tweedledum to Tweedledee. The Hawke and Keating governments generated a large body of commentary devoted to showing that the ALP had recently departed from “Labor tradition” or contesting that claim.

More than three decades on, the terms of debate have shifted, but the idea that the party consistently fails to act as its best self has become virtually integral to its identity. Labor is notable in attracting friendly, if sometimes severe, internal critics – members, activists and loyal supporters – who’ve felt part of the Labor tribe, yet also questioned how well the party was performing in its self-appointed mission.

This kind of interrogation has been more insistent since the 1980s, as many of the foundations on which the party was built – cohesive local communities, widespread deprivation, traditional male-dominated blue-collar industries, a large rural workforce, strong trade unionism and working-class identity – steadily eroded.

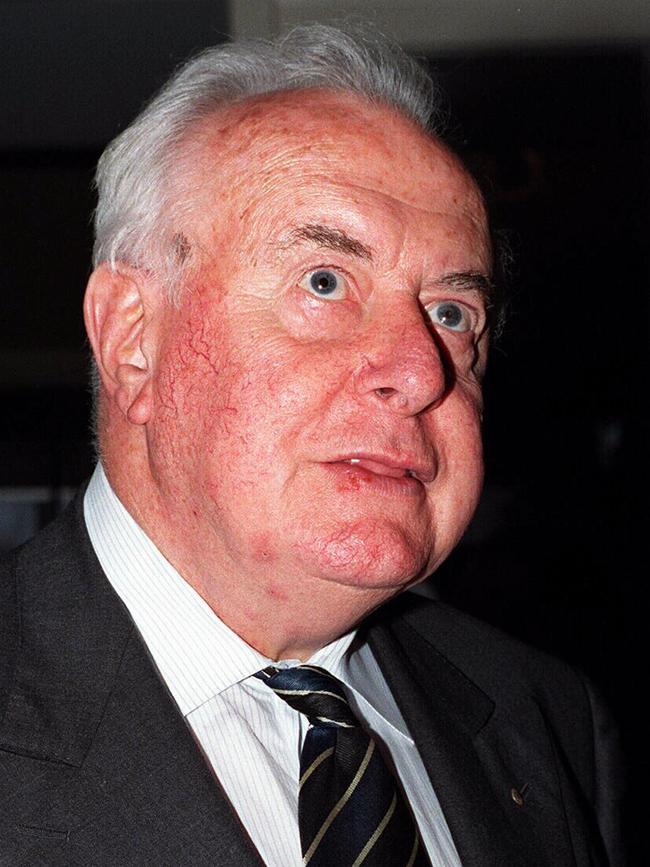

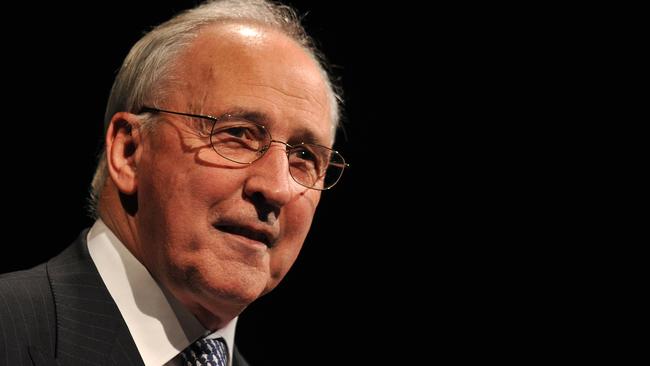

Self-criticism can be positive, but it also can be self-defeating if uninformed by a sense of historical context. A great deal of discussion within and about the ALP is carried on as if the issues at stake were being explored for the first time, instead of being – as they often are – variations on old themes. There are voters today too young to have any real recollection of even the Rudd and Gillard governments. No one under 50 has cast a vote for or against Bob Hawke; Paul Keating survives as the living voice from the days of the “Morphy Richards toaster”, which he famously satirised in a parliamentary attack on the Liberals; Watson, Fisher, Hughes, Scullin, Curtin, Chifley and Whitlam belong to ancient history, if their names are recognised at all outside the Canberra suburbs and federal electorates named in their honour.

At every point in its history, Labor has been able to renew itself only by examining, restating and sometimes redefining the goals of democracy, equality and social justice. Party machinery designed in the era of the railway and telegraph cannot be expected to advance the cause of a fairer and more decent society in the digital and artificial intelligence age. When Labor won elections in 1910, 1943 and 1972, social democracy seemed on the march. Even at the time of the 1983 and 2007 victories, by which time many of the party’s traditional commitments had receded, the scope for a renewed progressive politics still seemed broad.

The most basic fact about the history of the ALP is that it has endured three serious splits, two world wars and many crises. Yet today, political democracy itself is under siege around the world. Australia has been more successful than most democracies in the stability of its middle ground and the cohesion of its society, but it is not immune from the ills that afflict democracies elsewhere. Is it any wonder that Labor’s project of creating, and then sustaining, a viable electoral coalition now seems so daunting?

This is an edited extract from the updated edition of A Little History of the Australian Labor Party (second edition) by Nick Dyrenfurth and Frank Bongiorno, published by NewSouth, out next Wednesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout