Kyiv out in the cold as war fatigue sets in

Both Russia and Ukraine are digging in for a long war with no end on the horizon, and it is getting harder to maintain political will in the US and EU to keep funding Kyiv’s fight.

Ukrainian forces had not only stopped the Russian invaders but had driven them back in the north, east and south, leaving Russia in control of just 20 per cent of the country it had expected to conquer in a few weeks. The US and Europe were pledging bottomless pits of money to fund Ukraine’s brave fight for freedom in the biggest conflict in Europe since World War II. Ukrainian flags were hoisted atop buildings around the world in solidarity, and every twist and turn on the battlefield was front-page news.

That was then. Zelensky and his besieged country will enter 2024 in a very different and more dangerous place.

The battlefield triumphs of 2022 have long dissolved, replaced by gridlock along a frontline that stretches for 1000km.

This has become a grim death zone of strike and counter-strike with Russian forces in muddy trenches. Here success is measured in metres, not kilometres, with a field won or lost occasionally at enormous cost but with no overall change to the state of the war. Russia still controls the roughly 20 per cent of Ukraine that it did at the start of this year.

This deadlock is fuelling growing fatigue with the war in the US and the EU, the two financial powerhouses that fund Ukraine’s ability to keep Russian forces at bay. This has forced Zelensky to become a global fundraiser, crisscrossing the world in a desperate effort to keep international attention focused on Ukraine.

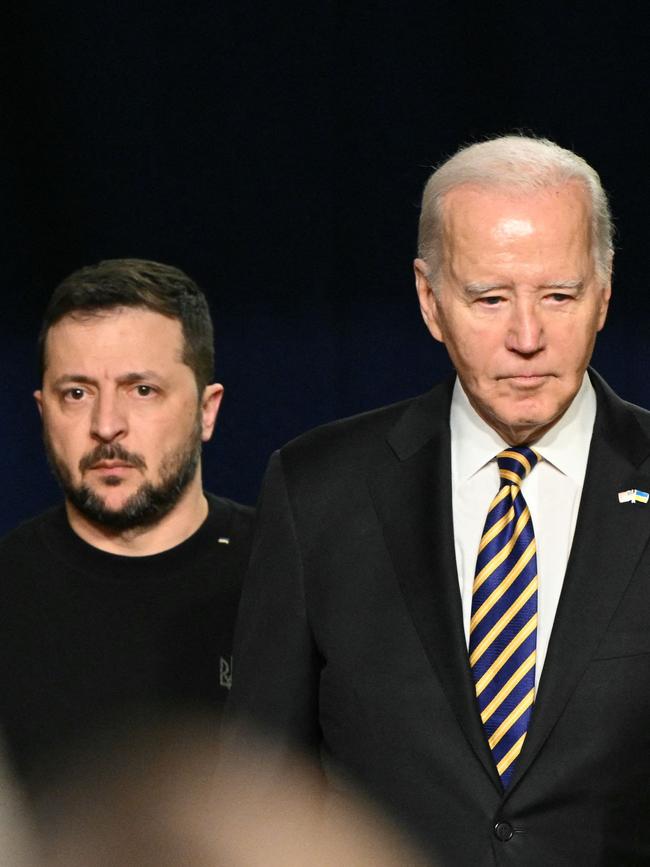

The Ukrainian President’s visit to Washington this month, his third since the war began in February 2022, could not have been more different from his triumphant visit a year ago. With growing opposition from Republicans to a new aid package for Ukraine, there was no grand speech to congress but, instead, a series of meetings behind closed doors with selected members of congress.

Zelensky’s task has become even harder since October 7, when the Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent Israel-Hamas war in Gaza diverted the world’s attention from Ukraine at the worst possible time.

“There is a loss of focus, a loss of collaboration and support for Ukraine,” Zelensky says of the war in Gaza. “It negatively affects Ukraine’s position and the aid.”

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin is in the Kremlin, biding his time, playing the long game and betting on the hope that the West will tire of endlessly funding Ukraine’s war effort.

“The reason the Ukrainians are gloomy is that they now sense not only have they not done well this year … they know that the Russians’ game is improving,” says Richard Barrons, a former British Army general. “They see what’s happening in congress and they see what happened in the EU.”

As winter sets in, further freezing any potential movement on the frontline, Zelensky is holding meetings with top American commanders about how to break the military deadlock in 2024 and with his own advisers about how to maintain the political will in the US and in Europe to keep funding Ukraine’s war.

The stakes for Europe could hardly be higher. A recent report by the Institute for the Study of War warns that Russia could conquer all of Ukraine if the US and Europe stopped providing military assistance.

“Such an outcome would bring a battered but triumphant Russian army right up to NATO’s border from the Black Sea to the Arctic Ocean,” it states.

There is a growing debate about how Ukraine should fight the war next year. Ukraine’s military commander, General Valery Zaluzhny, angered Zelensky earlier this year by admitting the war had reached a stalemate on the frontline – an admission Zelensky believed would make his task of securing military aid more difficult. Zaluzhny has since gone further, stating “there will most likely be no deep and beautiful breakthrough”.

The stalemate was largely caused by the fact Ukraine was forced to delay its planned counteroffensive from the northern spring until June because it did not have enough munitions and armaments. As Zelensky puts it: “This provided Russia with time to mine all our lands and build several lines of defence and, definitely, they had even more time than they needed. Because of that, they built more of those lines. And, really, they had a lot of mines in our fields.”

CIA director William Burns said it was painful to watch the Russians building vast lines of dragon-teeth anti-tank barricades, a spaghetti-line network of deep interconnected trenches and the most dense minefields seen since World War II.

“We could see them building really quite formidable fixed defences, hard to penetrate, really costly, really bloody for the Ukrainians,” he said.

The prevalence of drones on both sides means all major movements of troops or armour are detected early, removing the element of surprise and making advancing forces vulnerable to Russian strikes.

Both the Ukrainian and US commanders greatly underestimated the strength of these Russian defences and had unrealistic expectations that Ukrainian forces eventually would punch their way through and push towards the town of Melitopol and then on to the Sea of Azov, which would cut Russia’s land corridor to Crimea. Instead, Ukrainian forces are bogged down far from that coast near the village of Robotyne, a village they occupied with fanfare in August, but they have failed to penetrate farther south since.

The same type of strategic deadlock can be seen along the entire frontline, sparking debate about what Ukraine’s next step should be.

As Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba wrote in Foreign Affairs this month: “The current phase of the war is not easy for Ukraine or our partners. Everyone wants quick, Hollywood-style breakthroughs on the battlefield that will bring a quick collapse of Russia’s occupation.”

The most positive aspect of Ukraine’s offensive has been its attacks on Russia’s Black Sea fleet in Crime which has destroyed around twenty per cent of the fleet, including the sinking this week of another Russian warship. This has cruelled Moscow’s hopes of blockading Ukraine’s critical grain exports and has allowed Ukraine to keep its economy afloat.

The US believes Russia will launch a major offensive in the northern spring and American generals are pushing for a more conservative strategy for Ukraine to hold the territory it has and dig in rather than keep trying to advance at great cost to lives and resources. This move would give Ukraine time to receive more long-range weapons from the West and to finally get its donated F-16 fighters into the air to try to break the stalemate. The Ukrainians, however, are arguing that they need to keep attacking, not least to help keep the world focused on the conflict.

The Ukrainians believe the US is at least partly responsible for the stalemate by being overly conservative in its early reluctance to trust the Ukrainians with longer-range weapons that could strike at supply lines deep inside Russian territory.

Although the US has slowly loosened its restrictions on such weapons and belatedly has supplied the long-range Army Tactical Missile System, or ATACMS, to Ukraine, the Ukrainians say it is too little too late.

Frustration over Ukraine’s inability to penetrate Russia’s defences is spilling into the open. Criticism within Ukraine of Zelensky’s leadership is growing and military commanders are now seeking to mobilise up to 500,000 new soldiers to cover the large number lost through death or injury and to relieve those who are exhausted after almost two years of fighting.

But Zelensky’s main challenge right now is not at home but overseas.

In the US, on the cusp of a presidential election campaign, support is growing in Republican ranks to end US military support for Ukraine.

The US already has provided $US75bn in military, humanitarian and financial support to Ukraine, but Republicans in congress are refusing to approve a further $US60bn ($87.8bn) aid package unless the White House agrees to immigration reforms.

The linking by Republicans of funding for Ukraine to other non-related issues never would have occurred a year ago and shows how much more influence the isolationist wing of the party is exerting. Although these isolationist Republicans are still in the minority, their growing influence is a grave concern given what is at stake in Ukraine.

Joe Biden remains a fierce defender of Kyiv and says it is “stunning” that there is even a debate in the US about the need to fund Ukraine’s war effort. “Today, Ukraine’s freedom is on the line. But if we don’t stop Putin, it will endanger the freedom of everyone almost everywhere,” he said as he stood alongside Zelensky in the White House this month.

“History will judge harshly those who turn their back on freedom’s cause,” Biden said. “Putin is banking on the United States failing to deliver for Ukraine. We must, we must, we must prove him wrong.”

Zelensky’s greatest fear would be if Donald Trump, who is the clear frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination, were elected as president in November.

Trump has made no commitment to continue funding Ukraine and claims he would resolve the war in 24 hours by encouraging Zelensky to “make a deal”, which has been widely interpreted as forcing him to accept a negotiated peace.

Polls show that almost as third of Americans now believe the US is providing too much assistance to Ukraine, up from a quarter a year ago, but almost half still say the US is providing the right amount of aid or not enough aid to Kyiv.

Zelensky also has concerns in Europe, where populist Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has blocked the EU’s approval of an $82bn aid program for Ukraine.

Orban, a critic of Ukraine who has maintained cordial ties with Moscow and who opposes EU sanctions against Russia, wants to tie aid to Ukraine with other non-related issues between the EU and Hungary. Although the impasse is likely to be resolved early next month, it is a sign of what some in Kyiv fear is growing Ukraine fatigue in the EU.

Watching all of this from the Kremlin is Vladimir Putin, who would be reassured by Trump’s strong poll numbers and by the bitter debates over Ukraine in the US congress and the EU.

In a marathon four-hour press conference this month Putin said he intended to keep fighting until Ukraine capitulated.

“Peace will come when we achieve our goal,” he said, which includes the so-called “denazification” and “demilitarisation” of Ukraine. “The enemy announced a big counteroffensive. None of it worked anywhere. I don’t even know why they do this. They are just sending their men out to be destroyed.”

Putin also alluded to the debate in the West over support for Ukraine. “Ukraine produces almost nothing today, everything is coming from the West, but the free stuff is going to run out someday, and it seems it already is,” the Russian leader said.

Putin knows that time favours Russia rather than Ukraine. Ukraine is almost entirely dependent on ongoing Western support to keep fighting the war, and the longer the war goes on the more precarious that support is likely to become. In November next year, the US presidential election could result in Trump returning to office, dealing a blow to Ukraine.

On the battlefield, Russia also has the long-term advantage of having substantially more troops, weapons and equipment than Ukraine, a country with just one-third of its population.

Putin has put his country on a long-term war footing to continue the conflict indefinitely. In 2024 Russia is budgeting about $US160bn for its military, more than three times the amount before its February 2022 invasion. This is about 6 per cent of gross domestic product or 40 per cent of planned government expenditure.

According to US National Security Council spokeswoman Adrienne Watson, Putin “seems to believe that a military deadlock through the winter will drain Western support for Ukraine and ultimately give Russia the advantage despite Russian losses”.

The stalemate on the frontline inevitably has given rise to speculation that this frontline might one day become the new unofficial, or even official, border between the two countries. This would leave Russia with about 20 per cent of Ukrainian territory – up from the roughly 7 per cent it already controlled before the invasion.

Under a speculative future peace deal, Ukraine would give up its claims to the 20 per cent of the country already occupied by Russian forces in return for membership of NATO and the iron-clad security guarantees that come with it.

But this deal – or any other form of negotiated peace – is unlikely to be discussed in any serious form in 2024.

Zelensky says he intends to keep fighting until Ukraine regains all of its territory, including Crimea. He still has strong public support for the war, with a poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology showing 80 per cent of Ukrainians are opposed to giving territorial concessions to Russia. There would need to be a dramatic change in the state of the conflict for Zelensky to consider any form of negotiation.

Putin has even less reason to negotiate for peace, knowing time is on his side politically and militarily. For Putin, a peace deal in which Russia keeps the Ukrainian territory it already occupies would be problematic given his rash decision in September 2022 to annex four eastern oblasts when Russian troops occupied only parts of those regions. Putin is unlikely to agree to any settlement that contains less territory than he has annexed.

For now, both Zelensky and Putin are openly hostile to any discussion of peace or negotiations, with their respective positions being so far apart as to make any talks pointless.

Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Kuleba says a ceasefire would only help Russia.

“Some analysts believe that freezing the conflict by establishing a ceasefire is a realistic option at the moment,” he says. “Proponents of such a scenario argue that it would lower Ukrainian casualties and allow Ukraine and its partners to focus on economic recovery and rebuilding, integration into the EU and NATO, and the long-term development of our defence capabilities.

“The problem is not just that a ceasefire now would reward Russian aggression. Instead of ending the war, a ceasefire would simply pause the fighting until Russia is ready to make another push inland.” He says any deal to draw a border at the frontline would “condemn millions of Ukrainians” to “repression under (Russian) occupation”.

As the war approaches the two-year mark, a solution has never seemed further away. Both sides are literally digging in for a long war, with no end on the horizon. For Ukraine, 2023 was a disappointing year after its triumphs of the previous year. In 2024, Zelensky needs to somehow change the course of the war to keep the hope of ultimate victory alive and help ensure that the West keeps paying for it.

The stakes for Europe and for the free world could not be higher but it will be Zelensky’s biggest challenge yet.

A year ago last week, Volodymyr Zelensky received a hero’s welcome in Washington, where the wartime leader’s historic address to a joint sitting of congress drew comparisons to Winston Churchill.