Justice extends past our own backyard

The same principle that smashed native title could apply to any property rights.

Most major High Court cases are one part boring, two parts hysterics from ideological opponents. It is not often you get an element of grim humour.

But the Gumatj case, confirming that Indigenous holders of native title rights are constitutionally entitled to just terms when those rights are compulsorily acquired, is one of those cases.

The decision is vitally important for its impact on Indigenous native title holders and governments wishing to acquire their land, often for ultimate use by mining companies and other commercial concerns.

But that importance does not detract from the hilarity of the outcome in terms of some hysterical rhetoric of the No side in the recent referendum on an Indigenous voice.

First, the serious bit.

The Gumatj decision is exceptionally simple by the arcane standards of constitutional law. It is about whether native title rights count as property under the Constitution.

The point is that the Constitution guarantees that the commonwealth government cannot compulsorily acquire anyone’s property unless it does so on just terms.

So, when the Australian government passes legislation giving other people rights – total or partial – over traditional Indigenous land where native title exists, does it have to give just terms? This is as simple as it gets under the Australian Constitution.

The question is, are native title rights property?

The High Court has always given a wide meaning to the concept of property for the purposes of constitutional acquisition.

This is not a recent brain flash by Mr Justice Woke. It is an approach that goes back to when Moses was chief justice of Australia, and even further.

The founders of the Constitution wanted a wide definition of property, to assure citizens of due protection.

Through the years, property has gone well beyond Darryl Kerrigan’s backyard or the farm at Almond Grove. It includes not only things such as copyright but also vested rights to compensation under this or that commonwealth statute.

Native title is not the same as ownership of suburban land, but there are some similarities that scream “property”.

The essence of property in land is the right to use it in some way or other without the interference of others. Leases, licences and mineral rights are all examples of property.

So where does native title fit in? Sometimes it means the right to exclude all others. Very often, it is the right simply to use the land for purposes of hunting, ceremonies and protection of deeply cultural sites.

But all these rights conceptually are property. They are entitlements in and over land to be exercised above and beyond the rights of others. Take them away, and you have to give just terms.

This is not constitutional sophistry. These are rights recognised and protected by the common law so often cited by traditional defenders of the legal status quo.

This was the point of the Mabo decision, accepted as good law by Australian courts now for 38 years. That makes one hell of a common law precedent.

In fact, there is no real constitutional issue here.

Once you accept rights to exclude others from traditional lands generally or for specific purposes are property, the Constitution protects them majestically and automatically.

The analogies are striking. Why should the right to hunt or use land for ceremonial purposes be inferior to some of the powerful rights to explore or extract minerals or to run stock?

For nervous souls, there also are serious limitations on the scope of the Gumatj decision.

First, any claimant to just terms actually has to prove native title. Contrary to much public opinion, this can be a long and difficult process.

Second, right or wrong, the constitutional protection for acquisition on just terms applies only to the commonwealth. The states can merrily seize property on whatever terms they like.

True, most states have enacted “just terms” provisions in their own legislation, but these always can be overridden by a state parliament.

All this means that the scope of the Gumatj decision in practice is restricted to commonwealth territories – such as the Top End and Canberra – and various commonwealth places, such as certain coastal reserves and post boxes.

The other great limit is that just terms do not necessarily mean money, though in many cases this will be the demand. Just terms could include acquisitions that still preserved traditional uses of the land, possibly in combination with a just terms payment.

The usual suspects will fume about this weak, woke concession to Indigenous radicals. They will demand reversal. But their options are limited to the impermissible and the impossible.

The problem is that the Gumatj decision concerned the constitutional meaning of the word property. That cannot be overridden by legislation, indignation or consternation.

The impermissible option would be stacking the High Court. This would be as futile as it would be improper. High Court judges sit until they are 72. Vacancies come up rarely. Judges once seated are notoriously unpredictable.

Then there is the impossible approach. As we have been told a gazillion times across the past two years of controversy over the voice, the only way to change the Constitution is by referendum.

Adherents of the No case have gloated over their victory in the final vote. But what they mention much less is the almost reflective disposition of Australians to vote against any referendum proposals. That put a gale behind their sail.

Generally, that popular negativity is well-founded. Our population knows we have a very good Constitution that should not lightly be altered. They also know that a lot of referendum proposals historically have been rubbish.

So, let’s imagine a referendum proposal that specifically targeted removing just terms from acquisition of native title rights. Two iconic and ironic arguments straight from the Jacinta Nampijinpa Price-Nyunggai Warren Mundine playbook would be wheeled up, but this time by those protecting existing Indigenous rights.

First, how can you ever contemplate pushing the Constitution aside? It was written by God and handed down to Edmund Barton on Mount Kosciuszko. Any change poses unimaginable dangers.

Second, and even more pointedly, this would be a proposal specifically about race. Only Indigenous people would have their native title property rights limited. We would have a constitutional division between two racial groups.

Non-Indigenous Australians would have full constitutional protection of their property rights unless acquired on just terms. But Indigenous Australians could have their property rights ripped off them without compensation by any passing commonwealth bureaucracy.

A dreaded constitutional partition of Australians by race. Sound familiar?

But the best bit would be the actual No case. How would the average Australian react to the line that the commonwealth was now coming after some property rights, without any requirement to compensate?

The same principle that smashed native title property rights could be applied to any property rights.

This is the razor-thin, sharp edge of a very nasty wedge. First they come after the native title of Aboriginal people. Then it’s your local cricket ground, favourite park or weekend walking track. Finally, it’s your own backyard.

What’s the difference once the constitutional principle is established that Canberra can rip property rights off anyone with the bad luck to be within its jurisdiction?

This is the No campaign from hell. I would love to run it.

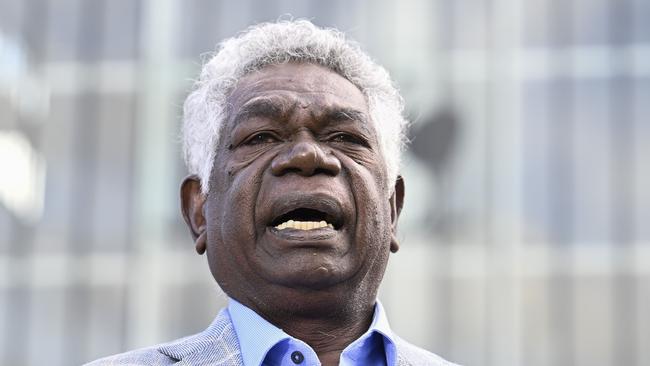

Greg Craven is former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout