It’s time for a good look back

Fifty years on from the start of the Whitlam era, this is how it should be remembered.

Yes, I would have loved to have been there, to have witnessed the shift in power. Not election night at the Cabramatta home on December 2, 1972. Not at the Yarralumla swearing-in of the two-man ministry of Whitlam and deputy Lance Barnard. Nor at the first caucus meeting of a federal Labor government since 1949.

For me the accession of Whitlam was captured by a meeting on Monday, December 4, 1972. The new prime minister sat in his Parliament House office with his foreign policy officials.

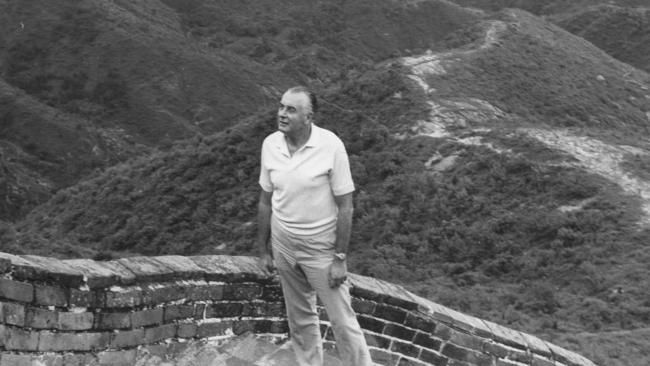

The first item was the start of negotiations on the opening of diplomatic relations between Australia and China. It was quickly disposed of. Whitlam had led from opposition anyway, visiting China in 1971, laying down the formula that shifted our embassy from Taipei to Beijing.

But there was another decision and it showed Whitlam at his savage, cutting-edge best. Whitlam told the diplomats that the Australian vote on the resolutions on Southern Africa in the UN General Assembly will be reversed immediately. Simply reversed.

Stephen FitzGerald, about to be appointed ambassador to China, recalls that the officials were reluctant. They suggested it would be “precipitate”. They advised we should move to abstention, not support. But Whitlam asked ‘how are our neighbours going to vote?’ When the officials started with New Zealand he interrupted them and said: “No, I mean our new neighbours, the countries of the Third World.”

Be clear what was happening. Under Coalition governments Australia had voted against UN resolutions critical of apartheid. That voting stance was a large part of our international character. We voted with colonial powers. We voted to protect states institutionalising racism. Our instincts were those of crown colony or banana republic.

In one meeting, two days after being elected, Whitlam swept that away.

Paul Keating’s observation that you change the government and you change the country has rarely been better dramatised. A different Labor leader would likely have accepted the departmental advice: shift from voting no to just abstaining; he might have agreed with the diplomats that a yes vote would be “precipitate”.

But Whitlam’s response was that of a leader who knew what he wanted and had confidence in his powers of persuasion. He was also an educated person in the broad sense, specifically someone from Australia’s liberal internationalist, university-educated middle-class employed in public service. It was from a tradition that had been advanced by Sir John Latham and Dr Herbert Vere Evatt. It embraced a belief in international conventions and took seriously the UN Charter. It had been honed by easy familiarity with academics and their work, attendance at worthy weekend confer-ences and airmail subscriptions to The Economist and The New Statesman.

His decision on our UN vote reflected confidence about a more independent Australian role in world affairs. This might today be considered the biggest part of what I like to call his conversation with the future of his country. The next day, at his first press conference, Whitlam used words that resonate as a sketch of what our character as a nation might be:

“… the general direction of my thinking is towards a more independent Australian stance in international affairs, an Australia which will be less military oriented and not open to suggestions of racism; an Australia which will enjoy a growing standing as a distinctive, tolerant, co-operative and well-regarded nation not only in the Asia and Pacific region, but in the world at large.”

Here is the notion of Australia as a creative middle-power, daring to see itself as more than US ally and complacent member of an Anglo-sphere. As he was to put it in January 1973: “For all its enduring importance, adherence to ANZUS does not constitute a foreign policy.” The Whitlam vision was of a nation with reputation for decent values (“well-regarded”) that could enlist soft power in the world stage and that, years later, could for example shape a Cambodian peace process or lead on a chemical weapons convention.

That he could promise to “take Australia forward to her rightful, proud, secure and independent place in the future of our region” shows in bold relief the gap between his boldness and the more dependent role Australia now cleaves to.

On domestic affairs his policy formulations, admirably simple, represented slabs of innovation, as with universal compulsory health insurance. He led his party away from its paralysis over state aid for non-state schools with an elegantly simple formula: Federal aid for all schools on the basis of need. That government munificence to private schools, without reference to need, is now the biggest source of inequality in Australian life, is the measure of how wholesome the Whitlam policy formula was, and how much we have lost in straying from it.

Labor suffered under the leadership of Evatt and Arthur Calwell, easily despatched by the superior debating skills of Robert Menzies. It left Australian Labor living off nostalgia for the Curtin-Chifley years. To us Whitlam held out the promise of reforming power, of a modernising era, a nation that no longer suffered from Donald Horne’s jibe that we were just a lucky country run by second-rate people.

He was not second rate. As my generation of teenage Whitlamites saw him, he might have been a frontbencher in the House of Commons, or a US Senator running in the presidential primaries. Even the great weakness of his administration – the lack of dexterity on economic policy – may be overtaken by the summation of Ken Henry that, under Whitlam’s economic stewardship, Australia simply reached OECD levels in its commitment to health and education. If his resources minister Rex Connor destroyed himself and damaged his prime minister with a muddled agenda, then it’s got to be said no subsequent government has found a means of levying from our resources sector the economic security that Norway has achieved.

When Whitlam stumbled in his plans for a national compensation scheme he was grappling with problems in tort law and support for disabilities that other governments would eventually have to deal with. His broadbrush tariff reductions paved the way for the economic reform agenda of the Hawke-Keating years. His elevation of women’s rights and Aboriginal land rights, his focus on non-English speaking migrants, discarded habits of thought that had been entrenched. We forget to what extent the Australia of 1972 was a young country with premature hardening of the arteries, a derivative society which struck American visitors and others as stubbornly English, still a colony in fact, which shuddered with fear of abandonment.

That Australian leadership might act bold and display confidence is the boiled-down essence of the Whitlam legacy. It’s the benchmark standard this statesman leaves his successors reaching for, and no mean contribution to how we might see ourselves.

Bob Carr is the longest-serving premier of NSW and was Australia’s foreign minister in the Rudd and Gillard governments. This is based on his foreword to The Whitlam Era: A Reappraisal of Government, Politics and Policy edited by Scott Prasser and David Clune to be launched on December 2 by federal minister Andrew Leigh at the National Press Club.

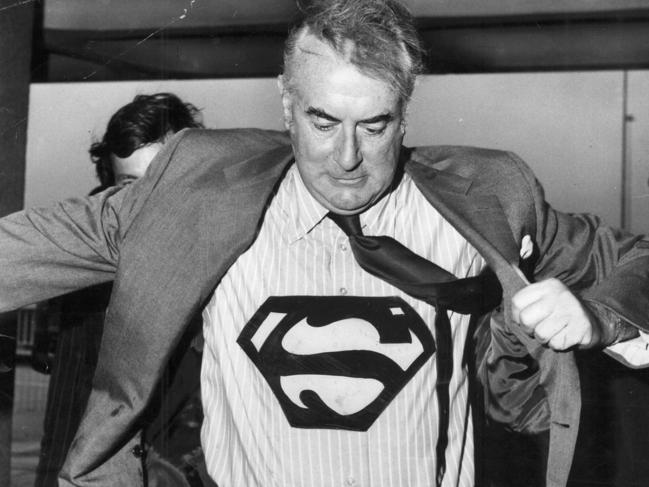

What an opportunity to witness the great man displaying what Graham Freudenberg called his “certain grandeur”, the title the gifted speechwriter gave his book on Gough Whitlam.