Gough Whitlam driven by a heroic excess of ambition

When he was good he was very good. And when he was bad, he was terrible. This is the Gough Whitlam I knew.

Whitlam came from a different age, having served in World War II – it was the age of Churchill and Roosevelt and epic events. Whitlam believed in the great man theory of history. He aspired to transform Australia, and during three turbulent, magnificent and chaotic years he succeeded, for better and for worse.

In his 1972 policy speech, drafted by Graham Freudenberg, Whitlam said: “There are moments in history when the whole fate and future of nations can be decided by a single decision. This is such a time.”

Whitlam unashamedly saw himself as a figure of destiny. In the end, however, his vision of himself was too large and egocentric for the country.

The Whitlam government never put down governing roots – Whitlam reformism was too rushed, too excessive, too sweeping, and, for many, too frightening. But this is the way Whitlam wanted it. No prime minister ever governed with the flamboyance, panache and enjoyment that he did. He turned the conventional wisdom on its head and made it look stupid.

Whitlam admired Sir Robert Menzies but he was far different from Ming. Whitlam was too impatient to follow Menzies’ wisdom in cultivating stability, consistency and reliability. Whitlam had great faith in the Australian people but, sitting in the PM’s office, he lacked guile and cunning as an interpreter of public sentiment.

Whitlam was a big man – he looked a PM and he spoke like a PM. Standing six foot, five inches (195 cm), Whitlam radiated political electricity everywhere he went – in the House of Representatives, walking across King’s Hall, striding the corridor of his VIP jet, engaging the gallery at his press conferences. He was incapable of acting small; everything he did he was magnified. Accordingly, his successes became epic and his flaws became catastrophic.

As PM, Whitlam was an educator, actor and prima donna. He fused arrogance with self-parody, immortalised in his line: “I don’t care how many prima donnas there are, as long as I’m the prima donna assoluta.” Asked what the new Albury/Wodonga growth centre should be called, Gough replied: “I think Whitlamabad would be appropriate.” Gough was an equal expert on the central European monarchies and the lack of sewerage in the western suburbs.

He was as didactic as he was confrontational. His reputation rested on his vote-winning ability but his flaw as PM was trying to govern on his own terms.

Younger people watching our 21st century PMs, from Kevin Rudd to Anthony Albanese, have no frame of reference to grasp what Whitlam was like.

His mind was an organised expanse of rationality but his temperament was explosive and egocentric. He rarely let opinion polls govern his behaviour – his prime ministership was based on the singular task of pursuing his reform agenda, his transformed vision of Australia. He assumed the people were with him – and they were, but only briefly.

If recent PMs have been reform shy, Whitlam was reform addicted. Gough was overloaded on vision but underdone on implementation. He was governing too fast to get the detail right.

He was an “all or nothing” leader, shunning concessions – in cabinet, caucus and parliament. His famous remark that “when you are faced with an impasse, you’ve got to crash through or you’ve got to crash” was how he operated. It’s heroic and dramatic, but hardly a modus operandi for successful governance. Whitlam’s personality was cut for a short, sharp, divisive, excitement-prone, hinge-of-history government. That’s what Australians got.

Few figures in our history can be called historically indispensable – but Whitlam fits that category. That’s because as we reflect at the 50th anniversary of Labor’s December 2, 1972 election victory that ended 23 years of Coalition rule the judgment is that only Whitlam could have returned Labor to office at that time.

Before that election, Labor had suffered nine successive election defeats. There were even doubts whether Labor would govern again, with the party before Whitlam’s leadership an old-fashioned rump run by old men with old ideas.

On February 8, 1967, Whitlam defeated Jim Cairns, Frank Crean, Fred Daly and Kim Beazley Snr to become ALP leader. His colleague, Lance Barnard, was elected as his deputy. It heralded the rebirthing of the party, based on a new generation and a shift to the right-wing. Labor’s two-party preferred vote at the 1966 poll had been a woeful 43.1 per cent which meant any recovery, if possible, would be protracted.

It is I believe a valid proposition that none of the other three leadership contenders possessed the ability to win the 1972 election. This is the sense in which Whitlam was indispensable to that victory. Only Gough could have done it. He saved Labor as a modern party. He had help and he had, in Mick Young, acting national secretary, a former shearer who grasped public sentiment and authorised the recommended advertising slogan from the agency: “It’s Time.”

It became the most memorable slogan in our political history. It didn’t sell a political message; it captured a mood, a vibe. The TV ads sought to humanise Gough. The campaign was pivotal because Australia was a conservative nation, women voters the most conservative, a nation still apprehensive about change, needing to be persuaded.

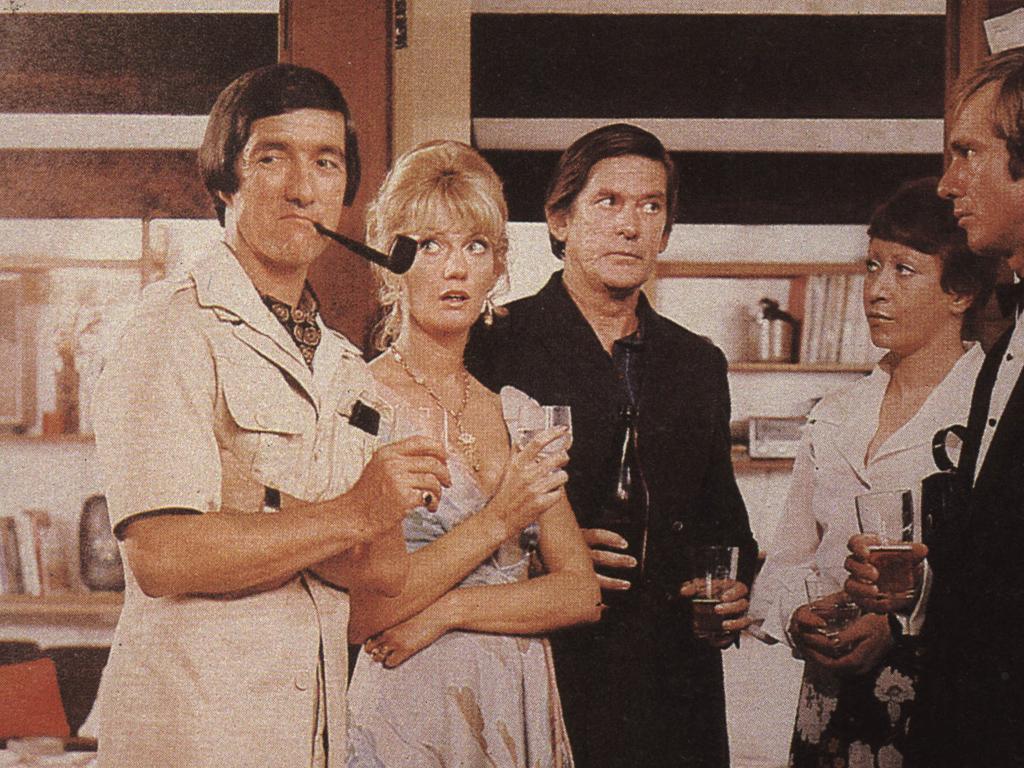

The “It’s Time” song helped with the pro-Labor arts community coming together including Alison McCallum, Bobby Limb, Dawn Lake, Col Joye, Jacki Weaver, Barry Crocker, Bert Newton, Jack Thomson, Judy Stone and Little Pattie. Patricia Amphlett, with a distinguished career in entertainment, is currently a director of the Whitlam Institute but was known at the time for her popular hit single He’s My Blonde Headed Stompie Wompie Real Gone Surfer Boy.

What hope did veteran Liberal PM, Billy McMahon, have against that? In truth, a lot of hope.

The reservations about Whitlam Labor ran deep. Many Australians heard but declined the “it’s time” vibe. Whitlam won a modest victory for a 67-58 seat majority. His win rested on a strange mixture – the most exhaustive program ever put to the people sold with showbiz razzamatazz. But the narrow margin meant the public was dubious, even at the start.

Whitlam revealed his character from the opening moment. Elected to parliament in 1952, he had waited 20 years in the wilderness. “The real drama of the changeover lay in its novelty,” he said. Not since 1929 had Labor formed a new government at an election. Whitlam was burning decades of humiliation behind him.

Unwilling to wait for caucus to elect the ministers, Whitlam got the governor-general to swear himself and Barnard into a two-man government. Gough had 13 ministries, Lance had 14 ministries. What else would a sensible PM do? The duumvirate, as it was called, symbolised the new order. Whitlam said it was the least expensive ministry Australia had ever had – then he joked there was one minister too many.

Years later, Freudenberg made a reappraisal – the Whitlam government had begun with a symbol of unconventional governance. Its bookends were the duumvirate in 1972 and the dismissal in 1975. The unorthodoxy of the duumvirate would meet its match in the unorthodoxy of the dismissal. These bookends suggested a government that always walked on the edge.

Whitlam was a brilliant catalyst for a media undergoing generational change and escalating self-confidence. No PM created as much news as Whitlam. The difficulty for Labor, as time advanced, was that too much was bad news. Whitlam made political journalists more important and self-important. Covering the Whitlam government was the wrong way to think about the job. You lived the Whitlam government, 24/7, long days, late nights, constant briefings, crazy rumours, there were insiders and outsiders, angels and demons, you wrote for the first edition, rewrote for the second edition, went overseas with the Sun King and spent the weekend at parties with loyalists, policy wonks and conspirators. An evening visit to the non-members bar before deadlines became a career necessity during parliamentary sittings.

The bar, packed with staffers, advisers and politicians, operated as the most crowded, intense and concentrated information exchange venue in the country. Journalists wrote, drank and kept silent on many of Labor’s indiscretions.

You learnt never to dismiss the wildest speculation – Lionel Murphy “raided” ASIO headquarters, DLP leader Vince Gair was lured into becoming ambassador to Ireland, Whitlam slashed tariffs 25 per cent, to Treasury’s horror Rex Conner was authorised to chase a $US4bn overseas loan through a Pakistani money dealer; Whitlam sacked Crean as treasurer, then he sacked Cairns as deputy PM, finally he sacked Connor as minerals and energy minister, only in late 1975 to find Sir John Kerr sacked him.

Whitlam arrived with the most developed policy program of any PM since World War II – his plan was to use the commonwealth’s financial power to improve the lives of people through assistance and tied grants designed to promote equality of opportunity and inject the national government into new areas.

His 1972 policy speech was a landmark – marking a high tide of faith in government and centralisation of power. The speech was lofty, comprehensive, utopian and naive. It took to a zenith the post-war belief that every problem could be solved by more government and more money. The speech was explicit about funding – fiscal drag would do the job.

The scale of Whitlam’s agenda was financially unsustainable. He came to power at a time of rising domestic inflation which required spending restraint not largesse, and he was unlucky because he arrived just before the 1973 oil price shock that saw stagflation overtake the global economy. Circumstances were against him.

What is the Whitlam policy legacy? The answer lies in the Whitlam paradox – there was good Gough and bad Gough.

Whitlam’s achievements were enduring. He did change Australia. Many of the social benefits we now take for granted were bequeathed by the Whitlam government.

The greatest was Medibank and universal health insurance. This was the government’s most contested policy struggle waged by its outstanding minister, Bill Hayden, against the Coalition parties and the private health insurance funds.

Abandoned by the Fraser government, the scheme was re-established by the Hawke government as Medicare. It remains enduringly popular.

In terms of changing social values, the most important reform flowed from the Family Law Act and no-fault divorce. Whitlam famously moved the second reading wearing a dinner suit having come from a black-tie event. The bill, eventually, was passed on a free vote for MPs. It was the first stage in Labor’s march from social conservatism to progressivism, with Labor ready to break from the Christian churches.

Whitlam introduced large-scale private school funding on a needs basis, effectively ending the sectarian divide in our national life. He laid the foundations for Aboriginal land rights, having established a royal commission conducted by Justice Edward Woodward, saying the ambition for which he wanted his government remembered was delivering “justice and equality” for Aboriginal people. To the surprise of many, the Fraser government proceeded to pass the bills.

On the environment, Whitlam’s strategy was to ratify the World Heritage Convention and use the external affairs power to advance environmental causes. Whitlam established the Australian Heritage Commission and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. He also completed the abolition of the White Australia policy and turned Labor into a party that championed migrant communities.

His government enshrined “one vote, one value” in electoral law, passed the 1975 Racial Discrimination Act, introduced the new system of Australian honours, completed the abolition of Australian appeals to the Privy Council, established the Australian Council for the Arts, and ratified international conventions to advance human rights.

Serving as foreign minister as well as PM for the first year, Whitlam sought to change Australia’s standing in the world, saying foreign policy was a project in “the intelligent anticipation of change”. His declared mission was to purge Australian policy of racism and fear of foreigners. As ALP leader, he had sought to oppose the Vietnam War but preserve the US alliance. As PM, the hallmarks of his foreign policy were the establishment of diplomatic relations with China, a Labor triumph Malcolm Fraser subsequently embraced, insisting on independence for Papua New Guinea (with Whitlam telling our security agencies he didn’t want the new government being bugged), a greater commitment to South East Asia, and the search for a special rapport with Indonesia.

Whitlam was an optimist about the world; he didn’t think in terms of security threats and balance-of-power geopolitics. His knowledge was phenomenal – I always said travelling overseas with Gough was like travelling with the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

But bad Gough was ever-present. Spending and tax skyrocketed. Whitlam was uncomfortable with economic policy and waited too long to appoint Hayden as treasurer. Confusion and internal rivalry plagued economic policy making. The upshot was public disenchantment as inflation and unemployment rose and decades of post-war certainty evaporated before a shocked electorate.

The government was suspicious of business and unable to turn its trade union ties into a plus. Whitlam and Bob Hawke co-operated occasionally but frequently sent thunderbolts at each other. In three years, spending as a proportion of GDP rose from 18.4 per cent to 24.1 per cent.

Labor was branded as an incompetent economic manager and the subsequent Hawke-Keating government saw Whitlam as the anti-model on economic management and reform.

Whitlam faced the people at five elections: in 1969 when he won the greatest swing to an opposition; in 1972 when he won office; in 1974 when he became the first Labor PM to be re-elected; and in 1975 and 1977 for landslide defeats, far greater than any of his victories.

The Labor hero was repudiated on an unprecedented scale by the people.

The origins of the modern Labor Party lie with Whitlam – by appealing to migrants, academics, young people, environmentalists, professionals and women he built a middle class progressive wing onto Labor’s working class base. His prestige diminished during the Hawke-Keating years when there was a more successful ALP government succeeding where he failed – delivering economic reform with equity, and creating a far superior model of Labor governance. It recovered somewhat during the flawed Rudd/Gillard era when Whitlam’s reformist courage loomed as the lost element in contemporary Labor.

Whitlam was never a populist and had a limited popularity. He never connected with the people in the manner of Hawke or John Howard. Whitlam was a loner, deficient in team management, a visionary, but weak on policy design and never able to reconcile his beloved program with the economic challenges he faced.

Yet he thrilled his supporters and transformed many lives.

Hayden said “the most fulfilling, exciting days in my life were with Whitlam”. Many others would agree. The Whitlam era is secure as a hinge-of-history event that saw Australia redirected as a country. The conundrum of good Gough and bad Gough is always with us but, for those who knew him, the memory of good Gough glows far brighter.

When he was good he was very good. And when he was bad, he was terrible. But Gough Whitlam was always compelling. Whitlam was a freakish political product, never likely to be reproduced. There could only be one Whitlam – charismatic, headstrong and fatalistic.