Is the Anthony Albanese, Jim Chalmers double act starting to crack?

The test will be whether the government is deemed by voters to be a culpable contributor to deteriorating economic conditions. The next election may well be won or lost on this question.

But whatever the political strategy is, there are cracks now starting to emerge in Labor’s political management plan for a once in a generation cost-of-living crisis.

So far the government has avoided any significant collateral damage that would otherwise threaten to erode the electoral goodwill Albanese has managed to preserve since the election.

But Labor is now in uncharted waters, presiding over the most rapid rise in interest rates since 1989 and the worst inflation in more than 30 years amid an energy price and supply shock.

What could possibly go wrong?

The most recent Newspoll published this week shows that while the Prime Minister’s net approval ratings are on a downward trajectory – having reached a peak of plus 33 in November last year to now plus 17 – it’s a trickle rather than a spiralling descent.

Nevertheless, the numbers are pointing in the wrong direction at a time when the economic indicators are also nosediving.

It may be some comfort that Kevin Rudd fell from greater heights over the same length of time – from plus 50s to plus 13 within a year of taking office – before rebounding again as crisis leader during the global financial crisis, only to plummet to catastrophic levels of unpopularity not long afterwards.

Albanese is no Rudd. And Labor claims to have learned valuable lessons from the last time it was in office. But just like his predecessor, Albanese came to office not expecting to be promptly engulfed in an economic crisis – albeit one of a completely different nature.

Cost of living is now the defining issue for the new Labor government. This is contested political space. Unlike the broader perception of economic management – which generally and historically favours the Coalition – cost of living can be won electorally by either side.

It went against the Coalition at the last election.

The new test will be whether Albanese ultimately is deemed by voters to be a culpable contributor to the deteriorating conditions. The next election may well be won or lost on this question.

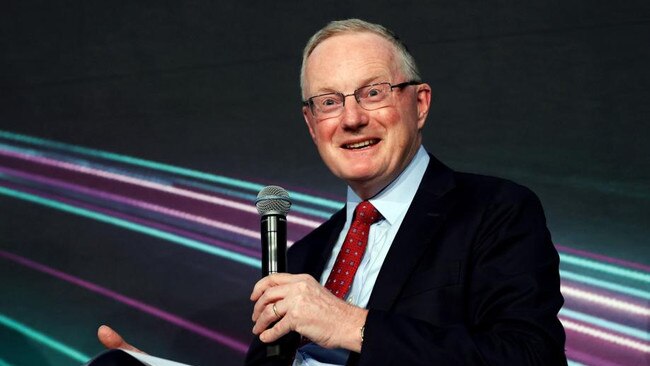

The answer to this largely rests with the competency of the central bank. And a good deal of luck. Reserve Bank of Australia governor Philip Lowe has been likened to Captain Chesley Sullenberger trying to land his crippled passenger plane on the Hudson River. One wrong move and the plane and its passengers are in deep trouble. The government’s political fortunes are also cargo on that plane. Going too hard on interest rates risks smashing the economy – the net effect being people losing their jobs. Going too soft would threaten a longer period of higher interest rates, inflation and the associated pain that would inflict over a protracted period.

Both outcomes risk perverse political problems of a different nature for the government.

Forced to choose which scenario would be more palatable going to an election within the next two years, an astute government would probably choose the former. Hence acute pain now to prevent longer-term disease.

Albanese’s re-election strategy is founded on an assumption that the inflation crisis has peaked and that economic conditions will begin to improve again by 2024, setting the government up for a 2025 election upon which it can claim it steered the country through the worst of it.

But a lot has to go right for the government for this to play out as Albanese hopes. And a lot of that rests on the decisions of the central bank.

At the same time, the Prime Minister will want to ensure that the inflation and the interest rate crisis doesn’t derail Labor’s ambitious broader social and economic reform agenda.

Within the next six months, Albanese will be taking the country to a referendum on the voice while embarking on a second round of even more controversial industrial relations reforms that will ignite a heated battle with business.

This will neatly coincide with almost one million mortgage holders coming off the soft blanket of fixed-rate loans onto the cold hard floor of 10-year high rates.

While Albanese may not have command of the monetary lever which is causing so many Australians hardship, he needs to control the politics.

But it is this very question of political management that has been left open to critical examination over the past three weeks.

There are those within government who are now questioning just what the political strategy is that inspired the Treasurer to start floating tax rises before the budget, amid a cost-of-living crisis.

The folly in this approach is twofold. The signal it sends to the electorate is that it is distracted from the essential issue that concerns them. Second, it creates a counter-narrative to the government’s claims to be alleviating cost pressures for families.

For the past three weeks, the political debate has been dominated by the doubling of concessional tax rates on super balances of more than $3m. While Newspoll shows that the policy was supported by a majority of voters, it is unlikely that those same voters believe this should be a priority issue for the government.

This has been compounded by the government’s new crackdown on franking credits, which has the potential to have more people agitated than with super.

The tax debate has other damaging political overtones – the appearance of a Prime Minister and a Treasurer at odds with each other over policy.

The political management of both issues has been clumsy and ill-planned.

And both issues have presented the Coalition with an opportunity to present Albanese as a leader of broken election promises and higher taxes.

Peter Dutton’s strategy is obvious. He wants to keep the focus on cost of living but also wants the government to appear distracted from the issue at the same time. This is a problem of the government’s own making. So far it has failed to bite electorally. There is no sign yet of significant damage for the Albanese government in the latest polls, which the Prime Minister would have met with quiet relief rather than concern.

Labor’s primary vote is still four points up on its election result to 37 per cent. At the same time, this is still four points down on its high of 41 per cent in opposition in the months leading up to the election.

The Coalition is back up to 35 per cent. And while this marks the tightest margin in the primary vote contest between the two parties since the election, it is still down at historically low levels for the conservative party.

On a two-party-preferred split of 54-46, the result reflects a two point swing to Labor since the election.

All this says that while Albanese still has political capital to spare, it may soon start to run dry just as he needs it most.

Much of his political authority is vested in the outcome of the voice referendum. A loss on this could severely diminish his leadership at a time of great economic uncertainty.

As households continue down the road of forced austerity with no sign that the government is responding in kind by tightening its own belt, Albanese may soon need to start sending strong signals that his government is focused singularly on the main game.

It’s by no means a come to Jesus moment yet for Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers.