Humiliation or war: who’ll blink on the brink?

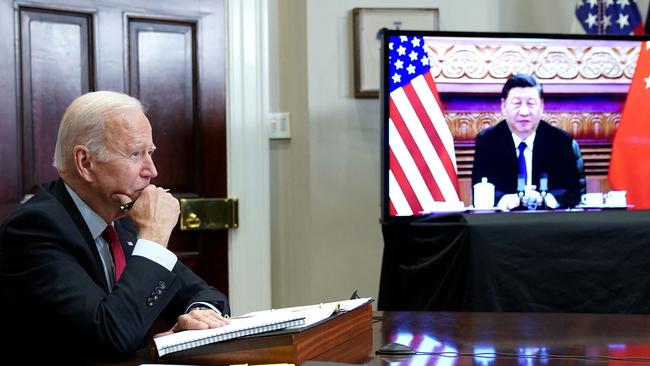

When the next Taiwan crisis flares, the US and China will face a deadly threat and a golden opportunity. This is how wars happen despite neither side wanting or intending them.

It is not inevitable that America and China will go to war over Taiwan, but the risk is real, and growing. If it comes, this war would be unlike anything we have seen for 75 years, and quite possibly unlike any war ever seen before. It would be the first conflict between major world powers since 1950, when China and America fought in Korea. It would also be the first serious war between nuclear-armed powers.

We must expect that once fighting began, it would swiftly escalate into a full-scale regional conflict, and nuclear war would then become hard to avoid. The consequences for America, for China, for the people of Taiwan and for everyone else in Asia and beyond would be immense, and disastrous.

And yet no one seems to be seriously trying to reduce the risk of this war happening. In fact, America and China, the key players, both seem content to allow the tensions to build. Neither side wants to go to war, but both sides think the possibility of a clash will serve their wider strategic aims. Washington hopes the threat of war will deter China from challenging America’s primacy in East Asia, and Beijing hopes it will deter America from trying to contain China’s ambitions. It is a very dangerous game, and one as old as power politics.

When great powers compete, a relatively modest issue acquires outsized importance as the focus of their rivalry and the test of their strength and resolve. This is how the Thucydides Trap is set. In 433 BCE, the fate of a minor colony on Corfu became the test of whether Athens or Sparta would dominate the Greek world. In 1914, Austria’s right to punish Serbia for the archduke’s assassination became the test of the entire European strategic order. In 1938, the Sudetenland became a test of the Western allies’ resolve to stop Hitler. And today, the future of Taiwan has, it seems, became the test of whether China or America dominates East Asia in the decades to come, and whether the post-Cold War vision of US global leadership can endure.

Taiwan’s role in this escalating rivalry is not surprising. It has been the most sensitive issue in US-China relations ever since America “lost” China to the communists in 1949. Beijing has since then seen the assertion of its sovereignty over Taiwan and its right to take control of it – by force if necessary – as fundamental to its place as a power in Asia. And America has seen its capacity to deny Taiwan to Beijing the same way.

In the 1970s, awkward compromises were reached to reconcile these inherently incompatible positions. Those compromises, which have framed Taiwan’s unique international status for the past 40 years, were sustainable as long as both sides were determined to make the relationship work. That is no longer true, and the compromises are coming apart.

The precarious status quo over Taiwan is under pressure from developments both within Taiwan and beyond it. Since Taiwan’s transition to democracy in the 1990s, it has become less and less likely that its people will ever willingly agree to be brought under Beijing’s control, as Beijing has long hoped. This has become especially clear in the past five years, since the election of President Tsai Ing-wen. Under her predecessor, Ma Ying-jeou, it seemed possible that as China grew richer and – as many expected – less authoritarian, the people of Taiwan would come round to the idea of unification.

But Tsai’s successive election wins, based on little more than her anti-Beijing credentials, have confirmed the opposite is happening. The Taiwanese have become more opposed to unification as China becomes more authoritarian, especially since Beijing has clamped down on Hong Kong. This must raise fears in Zhongnanhai that the time for patience is past, and that unification needs to be achieved sooner rather later. At the same time, Taiwan’s vibrant democracy makes it harder for Washington to stick to the limits on interactions with Taipei that were agreed on 40 years ago, when Taiwan, too, was a dictatorship, and increases the pressure to shield Taiwan from Chinese oppression.

The impact of these trends on Taiwan’s predicament is greatly amplified by the escalating strategic contest between America and China. This is a contest between the world’s two strongest states over which of them will lead the globe’s most dynamic and prosperous region in the decades ahead. America wants to preserve the dominant position it has held and successfully defended for over a century. China wants America to withdraw from East Asia so it can take its place as the region’s primary power and at least the equal to any power globally.

For both countries, the outcome is fundamental to their identities as nations. The stakes are therefore high. Great powers do not go to war with one another lightly, but these are the kind of stakes for which, throughout history, they have done so. If America and China go to war over Taiwan, it won’t really be about Taiwan, any more than the First World War was about Austria’s right to punish Serbia. It will be about the shape of the future regional and global order.

To understand the likelihood of a war over Taiwan, we need to understand how Washington and Beijing use the possibility of war in their contest for leadership. Leadership in an international system is largely built on perceptions. A country is treated as a leader if it is perceived as such. Many factors contribute to building and maintaining perceptions of leadership but the deepest foundation of leadership is the perceived willingness and capacity of a country to use force to assert its will. That is what both attracts followers and deters adversaries.

America’s leadership in Asia over many decades has been founded on the perception among Asian nations that it is willing and able to use force to protect its friends and punish its enemies – even against other great powers. Above all, its leadership has been based on the unwillingness of either Japan or China to risk a war with it, accepting subservient places in the regional order. The need to preserve such perceptions is the reason that America has invested so heavily in the kind of high-level forces that would only be needed in a major-power war.

This makes China’s task clear. To undermine US leadership and assert its primacy in East Asia, Beijing must change perceptions in the region about America’s capacity and resolve to fight and win a war with China. Beijing must show that as its power has grown, the balance of strength and resolve has shifted its way – that it is willing and able to fight America in East Asia, and America is not willing to fight China. America’s task is equally clear. To preserve its leadership, it must show that America, not China, is willing to fight.

Taiwan is not the first or the only issue the two powers have used to test one another. Since 2012, the South China Sea has been the focus of a preliminary round in the contest. By defying Washington’s loud protests, China’s provocative actions there have tested America’s willingness to defend the principles of international order it accuses China of violating. But any action with a real chance of forcing China to stop doing things like building island bases risks a clash that might escalate into a war, and Washington has not been willing to take that risk. China has won that round.

Now, as their rivalry grows, the contest moves to Taiwan, a clearer and more dangerous test. It was always a little hard to believe either America or China would really risk a war over the rocks and reefs of the South China Sea. But Taiwan is different: both sides have long asserted their willingness to go to war over it, even when the relationship has been at its warmest. To repeat, neither side wants a war. They both hope to win the contest by forcing the other side to back off, thus destroying their rival’s leadership credentials.

When the next Taiwan crisis flares, both sides will face a deadly threat and a golden opportunity. If America abandons Taiwan to avoid war, its strategic credibility in Asia will be destroyed.

Washington has always made it crystal clear that behind the artificial ambiguities of its One China policy lies a commitment to defend Taiwan – a commitment as strong as the one to its formal allies in Asia. If Washington now decides the cost of defending Taiwan against today’s powerful China is too high, those allies – Japan, South Korea, The Philippines, even Australia – would naturally, and rightly, doubt America’s willingness to defend them either. Non-allies such as Indonesia and Vietnam will be even less inclined to rely on US support. Countries across the region would have less reason to side with America, and more reason to deal with China as best they can.

That is how strategic leadership shifts. The US alliance system, and its position as an Asian power, would crumble. China would take its place. Conversely, if China backed off, its claim to America’s position in Asia would collapse, and US leadership would be resoundingly affirmed – at least for a while. The communist government in Beijing would suffer a devastating blow to its standing, and perhaps even to its domestic legitimacy.

So, as the next Taiwan crisis unfolds, both sides will have a big incentive to talk and act as if they are prepared to fight, hoping and expecting that this will deliver them a costless victory by making the other side back down.

But there is a fair chance they will both be wrong about this. Both will face a disastrous choice between humiliation and war. In such situations, leaders in the past have often chosen war. This is how wars happen despite neither side wanting or intending them.

This is an edited extract of Hugh White’s Reality Check in the latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs: The Taiwan Choice, out Monday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout