What’s driving America’s murder wave

Violent crime is surging across the US, reversing a generation of progress. But the disastrous experiment in defunding the police is only part of this complicated story.

Twice in a fortnight mid-town Manhattan has stood still as thousands of New York City police officers paid tribute to more of their murdered colleagues.

Wilbert Mora, 27, was shot along with his colleague, 22-year-old Jason Rivera, answering a 911 emergency call in Harlem late last month.

New York City, once the murder capital of the Western world, is enduring a surge in killings that began in early 2020, fuelled by a simmering suspicion of police after the death of George Floyd almost two years ago, a boom in gun purchases and the tumult caused by Covid-19 restrictions.

Last month Deloitte consultant Michelle Alyssa Go, 40, was minding her own business, waiting on a New York City subway station platform, when she was pushed in front of an oncoming train, allegedly by mentally ill homeless man Martial Simon – a chilling reminder the crime wave isn’t limited to internecine gang wars or dangerous behaviour.

Since 2019 the number of murders in New York during the course of the calendar year has soared more than 50 per cent to 485 last year, the highest in a decade. The drip-feed of grisly stories only scratches the surface of the US murder wave, which isn’t limited to New York.

“I hear gunshots every day,” Angela Hernandez-Sutton, who lives on Chicago’s West Side, recently told the city’s Sun-Times newspaper. “I just listen to hear where they’re coming from, then move to the front or the back of the house.”

It’s a national trend that increasingly is concentrated in the suburbs and smaller cities. A generation ago one in five murders was in Chicago, New York or Los Angeles; now it’s about 7 per cent, says Jeffrey Asher, a former CIA officer and data analyst specialising in criminal justice data.

Some US cities, including Albuquerque, Memphis, Milwaukee and Indianapolis, experienced their highest number of murders last year.

Others had their biggest annual increases. In Austin, the “bluest city” in Texas, murders jumped 87 per cent last year to 88. In Las Vegas, the number of murders grew 44 per cent to 147. Oklahoma City was up 35 per cent to 66. By way of comparison, in the entire state of NSW, with a population of eight million, 99 people were murdered in 2020, 17 fewer than 2019.

“It was a pretty uniform rise across the country in 2020, in both Trump and Biden counties, red and blue states and cities,” Asher, who is based in New Orleans, says.

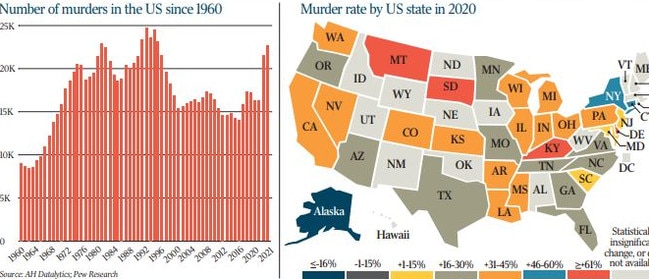

Final figures for last year aren’t yet available for the whole country, but Asher is forecasting at least a 6 per cent rise from the 21,500 Americans murdered in 2020, which was itself the highest number since 1996 and the biggest percentage increase on the previous year since 1905.

“The numbers are horrifying by the standards of Australia; it’s incredibly tragic and shocks the conscience that we don’t feel we need to do more about this,” says Maryland Public Policy Institute chief economist Stephen Walters, author of Boom Towns: Restoring the Urban American Dream.

Murder rates had been trending steadily down in the US since the mid-1990s, which experts variously attributed to tougher policing and improving living standards that have helped drag down violent crime across the developed world for many years.

What explains the sudden rebound in the US, reversing a generation of progress, isn’t clear.

“The easy answer is it’s complicated; anybody saying it’s x or y is pushing an agenda or is plain wrong,” says Asher. “And it’s important to realise there hasn’t been an increase in crime overall, except for murder, where it’s been a pretty dramatic rise.”

Murders make up only a tiny share, about 0.2 per cent, of all crime in the US, which the FBI divides into four main categories: murder, rape, robbery and assault, and property crime, such as burglary or car theft, which makes up about 80 per cent of all crime by the number of incidents.

Burglaries have fallen nationally in 11 of the past 12 years, including in 2020 when they fell 7 per cent. Rapes and violent assaults are down too.

“We’re still arguing about crime decline in the early 1990s, so don’t expect a good answer on all this,” says Jesse Jannetta, a criminal justice expert at Washington, DC think tank the Urban Institute.

The murder of Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 unleashed a wave of violence and nationwide riots in which at least 25 Americans were killed. It spurred an outpouring of contempt for police across the US that had no precedent.

“As we have said before, the recent erosion of respect for law enforcement and anti-police rhetoric (have) fuelled more aggression towards police officers than what has been seen in previous years,” Fraternal Order of Police president Patrick Yoes said last month.

The number of police officers shot in the line of duty last year increased to 346 (63 of whom were killed), up from 293 shot (and 50 killed) in 2019.

“It’s so difficult to contemplate why someone would sign up to do this job,” Walters says, referring to the killing last year of Keona Holley, 39, a relatively new police officer in Baltimore who was shot in an ambush while she was sitting in her patrol car in the early hours of December 16. She died a week later.

Jannetta says police budgets overall haven’t been cut, except in a few cities such as Seattle and Los Angeles, where budget cuts quickly were reversed. “We did see a reduction in custodial arrests in a lot of places, and whether police themselves pulled back in response to the Floyd murder, that’s more of an open question,” he says.

At the same time that respect for policing had been dragged through the mud, pandemic restrictions crippled the US economy, causing widespread social dislocation. Almost two years later total US employment is still about three million jobs smaller than in February 2020.

“We know that attachment to positive institutions, whether school or work, is a protective factor against getting involved in crime of all types,” Jannetta says.

Others point to guns, whose purchase is legal thanks to the US Constitution’s second amendment. According to research by health sciences and epidemiology professor Matt Miller of Northeastern University in Boston, between January 2019 and May last year 7.5 million Americans, or 2.9 per cent of all adults, became new gun owners – 5.4 million of whom were in households where no one had a gun before.

“If a tiny fraction of assaults, where otherwise there wouldn’t have been a gun, end up in a shooting instead of a stabbing, then you’re looking at a big percentage impact in murders,” Asher says.

Those who doubt the role of additional guns point out there are already more than 400 million guns in the US, making new purchases a relative drop in the ocean.

Violent crime is mainly a city and county-level responsibility in the US. But as leader of the Democratic Party, parts of which championed “defund the police” in 2020, President Joe Biden has lost significant political capital as the number of murders grows.

More than half of Americans last year, up from 38 per cent in 2020, say crime in their areas is higher than a year ago. And the belief that crime is “up nationally” was 74 per cent, near the highest level in 25 years, according to consistent polling by Gallup.

Initially dismissing the murder wave for much of last year, Democrat politicians have sought to ditch anti-police activists within their party and blame factors beyond their control.

“I think a root cause in a lot of communities is the pandemic,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said in a recent press briefing.

All talk of defunding the police among Democrats with responsibility over policing has evaporated. New York City elected a former police officer as mayor last year, Eric Adams, who has vowed to crack down on crime.

Even San Francisco’s left-wing mayor, London Breed, gave a rousing speech in December, shocking some Democrats, promising to “end the reign of criminals”. “And it comes to an end when we take the steps to be more aggressive with law enforcement … and less tolerant of all the bullshit that has destroyed our city,” she said.

A proposal to radically defang the police force in Minneapolis, epicentre of the defund the police movement, failed in November last year in a popular vote, 56 per cent to 44 per cent.

Baltimore, one of the most dangerous cities in the US, illustrates how disastrous widespread police defunding would have been.

“We started the ‘de-policing’ experiment years ago for different reasons, budgetary mainly; the ideological element that police are racist, and that efficient policing leads to mass incarceration, was added on several years later,” Walters says.

“There’s an important distinction between defunding and de-policing; not many police departments have smaller budgets, but they will have fewer officers as money is allocated to pensions, for instance.”

In 2011 Baltimore elected a mayor who radically reduced police numbers. Today, the police patrol the city’s 210sq km with 18 per cent fewer officers than a decade ago.

Thirty-six people were murdered in Baltimore in the first month of this year, the worst month in the city’s history.

In the seven years from 2015 to last year, in a city of about 600,000 people, more than 2330 people have been shot – about 0.74 per cent of the entire population and a 50 per cent increase on the previous seven-year period.

“Baltimore’s current rate of 57 homicides per 100,000 residents per year is seven times the national average and exceeds the rates for countries such as El Salvador (52), Honduras (39) or Venezuela (37), from which migrants routinely seek asylum in pursuit of greater personal safety,” Walters tells Inquirer. These are nations the US government advises Americans not to visit because of high crime rates.

In keeping with trends over decades, black Americans, about 10 per cent of the US population, experience gun homicides, gun injuries and shooting at the hands of police at 10, 18 and three times the rate of the white population. In Baltimore last year, more than 90 per cent of victims were black and almost half of those were black men aged 18 to 35.

“The homicide rate for this demographic was 347 per 100,000 population – slightly higher than the 335 per 100,000 killed annually in Operation Iraqi Freedom,” Walters says.

As brief and isolated experiments with defunding police end, and US society begins to return to normal, there’s a good chance that crime rates in the US will return to their long-term decline, in keeping with all developed nations. But it’s unlikely to happen quickly.

“Violence begets more violence. Violence cascades. A lot of things that happen in gun violence can be driven by retaliatory cycles,” Jannetta says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout