Howard and Costello GST experience shows the way for tax reform

The release of cabinet papers from the late 1990s offers lessons for today’s policymakers.

“They are the big five reforms,” Howard told me a fortnight ago. “There are other reforms but they are the big ones. Now, in my view, the one that had the greatest impact on our economy was the floating of the dollar. The one that was the hardest to implement and affected people’s lives more than anything else was the GST.”

What is telling about Howard’s assessment is that these reforms were implemented, or jointly implemented over time, by the Hawke-Keating and Howard governments. The major reform program began in 1983 and ended by 2007. It is not to say there have not been other reforms but, as Howard said, these are “the big ones”.

The release of the 1998-99 cabinet papers by the National Archives of Australia on Wednesday provides new insights into the difficulty of designing, advocating and implementing lasting economic reform. There are lessons, as ever, for today’s policymakers should they wish to heed them.

While the cabinet papers cover a range of matters — such as strict adherence to fiscal goals, the republic referendum, the work-for-the-dole scheme, school funding changes, the waterfront confrontation, a crackdown on welfare fraud, East Timor’s vote for independence, fears over the Y2K bug, terror risks, and more — taxation dominated cabinet business.

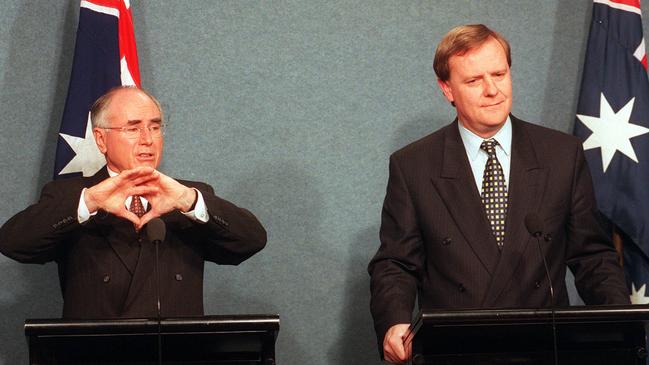

Howard and his treasurer Peter Costello announced their intention to overhaul the tax system in August 1997. It was to be a “great tax adventure”, the then prime minister said as they crisscrossed the country making the case for change.

The government’s plan, known as A New Taxation System, was announced in August 1998. The voters would have their say at an election in October 1998. Victory would provide a mandate for reform.

But ministers were uneasy about gambling the government’s future on a GST. Howard had promised before the March 1996 election to “never ever” introduce a GST. Costello told me two weeks ago that making the case for change, having a detailed policy, cabinet buy-in, approaching it methodically and mastering the detail were essential.

“We’d had a GST election in 1993 which the Coalition should have won but it ended up losing the unlosable election, so this spectre hung over all of us,” Costello says. “This was the stuff of nightmares. The lesson coming out of the 1993 election was don’t ever try and put a tax on everything because it doesn’t matter what else is happening, you’ll lose.

“(Former Liberal leader John) Hewson was destroyed on the detail of his own tax and so the general view was that if your political opponents could trip you up on detail, as Hewson had been tripped up on a birthday cake, you could implode at any moment.”

It was high stakes. The burden of taxation would shift from income to consumption, with a 10 per cent GST that would replace wholesale sales tax and some state taxes. The states would receive all the revenue. The base and the rate could not change without the states agreeing.

Howard outlined why they succeeded: “We were able to get it through due to a combination of there being a grudging acceptance that this was a reform whose time had come; an acceptance of the argument that it is better to tax spending than overtax income; and the fact that the two people who were charged with prosecuting the case understood the detail better than most.”

Nevertheless, he acknowledges the “chequered history” of attempts to introduce a consumption tax, including his own failure to convince Malcolm Fraser to broaden the indirect tax base in 1981. They needed a different approach. “It satisfied my two key principles of winning acceptance of reform in Australia,” Howard explains. “A, it had to be good for the country and, B, it had to be fair, and we went to great lengths to enlist people on the basis of fairness.”

This is where the cabinet also played an important role. Submissions and minutes constitute thousands of pages. Costello briefed ministers with a PowerPoint slide show. There were nine meetings in four weeks, often taking all day, as the package was finalised. Compensation elements — including reductions in income tax rates and special support for families, pensioners, self-funded retirees, welfare recipients and small business — were enhanced.

Ministers also wanted the benefits for “employment and wealth creation, efficiency, and business costs” emphasised by the treasurer. It was also important to argue to voters that “Treasury’s distributional analysis shows that no household type or income range loses as a result of the package”, a cabinet minute said.

While the government won the 1998 election, negotiations were still required with the states and the Senate. Howard and Costello said that if they failed another election, possibly a double dissolution, was not a viable option. Compromise was essential.

When independent senator Brian Harradine said “I cannot” support the tax package, made up of 27 bills, negotiations began in earnest with the Australian Democrats. A deal was reached, including exempting fresh food from the GST, in May 1999.

Implementation was also important. More than two million businesses, more than double originally anticipated, were required to register for an ABN and complete quarterly BAS forms. Costello says the taxation changes were not guaranteed until the Coalition won the November 2001 election, when Labor promised to roll the GST back. “You’ve got to explain to people what the problem is and you’ve got to explain to people how you are going to fix the problem,” he summarises.

“We had a three-year timetable and then defended it at a second election. You don’t just wake up overnight and say: ‘Hey I’ll do tax reform.’ You’ve got to have people who are on top of the detail and who the public has confidence in.”

These are essential lessons for the 2020s.

John Howard argues there are five landmark economic reforms that have fundamentally changed Australia for the better over the past 30-40 years: floating the dollar, dismantling the tariff wall, privatising government assets, decentralising workplace relations to allow greater flexibility and introducing the GST.