Authoritarian axis leaves Western alliance for dead

The democracies are in disarray and falling behind the dictators in a perilous fight for global dominance. We need to reverse this deadly dynamic.

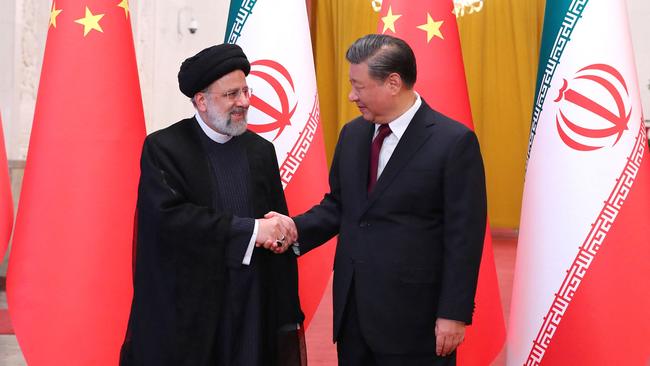

The other is led by China with its most powerful allies, Russia, Iran and North Korea, and a string of lesser allies still capable of causing a lot of trouble – Venezuela, Cuba, Cambodia, Pakistan, Laos and others.

Three developments starkly illustrate this new reality.

Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, for the first time in 24 years, visited North Korea. Kim Jong-un welcomed him with open arms, two dictators with a shared dream – weapons, survival, local enemies and a chance to smash the US and its allies.

Putin and Kim signed a pact promising each would come to the other’s military aid if it were attacked. This is a thickening of an already substantial alliance. The recent G7 summit condemned Beijing’s provision of materials to Russia that help it fight the war.

North Korea’s support for Moscow is more direct. North Korea is mostly a ramshackle state, but it’s very good at a few core military things. It sends millions of artillery shells to Russia in exchange for money and other military technology. Iran sends Russia tens of thousands of military drones. Russia makes enormous money selling its resources to China. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken says Russia couldn’t sustain war in Ukraine without Chinese help.

Military doves who want to limit defence spending often claim that this axis of authoritarians isn’t really made up of military allies. But they co-operate in military and security affairs in many ways more effectively than democracies typically do. They enjoy the dictator’s one advantage – single-mindedness.

The second development was Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s visit to Australia. Can any Chinese leader ever have made so fatuous a visit anywhere?

“Panda diplomacy” dominated, as though the Communist Party of China is nothing but a big, cuddly, cute bear, wanting only to dole out riches to Australia by lifting illegal trade sanctions it imposed contrary to its obligations under its free trade agreement with Australia, and under a sublimely absurd agreement that the two nations are “comprehensive strategic partners”.

Li was matched in gushing fatuousness by Anthony Albanese, who consistently displays stage fright whenever he finds himself in the simultaneous presence of senior Chinese and a TV camera.

But Li’s visit was bookended by two intrusions of reality. Before Li’s visit, Foreign Minister Penny Wong pointed out that Australia was in permanent strategic competition with Beijing in the South Pacific.

And as Li left, though conveniently after he had taken to the air, Australia joined the US, The Philippines and others in condemning Chinese aggression in Philippine waters, which Beijing claims for its own, that resulted in serious injury to one Filipino.

The visit aimed to recast China’s popular image, but reality kept interrupting.

The third instructive development was Peter Dutton proposing a nuclear power industry in Australia. In the context of the new cold war, this should be an obvious move. Nuclear power solves a long-term problem, producing permanently reliable near zero-emissions power. But it also transforms Australia, vastly strengthening our industrial potential and scientific capacity. Not just Australia but the democratic alliance would be strengthened by Australian nuclear energy.

However, the politics will probably prove insuperable. The Opposition Leader deserves credit for the commitment. But here’s the thing: the Coalition was in government for 10 years. There was overwhelming support for nuclear energy across the two governing parties. But, as with defence, nothing happened.

The Dutton initiative glumly fits the broader dynamics of the new cold war. Someone in each free society will propose effective policies, but overwhelmingly they won’t be adopted.

Australia is invited to participate in two fantasies. The first is that China and its allies, while disagreeable, won’t ultimately break the system. They are reasonable. We can negotiate an outcome. We must always de-escalate and establish good process, like Li’s visit to Australia.

The second, interlocking fantasy is that Australia and its allies, chiefly of course the US, are well prepared and would prevail in any conflict.

Both fantasies are entirely false. They lead to perhaps fatal complacency, not only in Australia but also in the US, Britain, France and in many of the allied democracies.

Just for a second, come on an excursion into ancient history. Ancient Rome was the most powerful imperial state the world had ever known. For centuries, its fall was unthinkable. Yet fall it did.

There had been other highly sophisticated states in the ancient world – the city-states of ancient Greece, the empire of Alexander the Great, the Persian Empire. Yet after a period of internal division, ineffective governance and military atrophy, Rome fell not to a civilisational peer but to the barbarians, who lacked Rome’s sophistication but had plenty of martial spirit.

The US and its allies, obviously, aren’t ancient Rome. And the strategic contest is not remotely decided. Each authoritarian regime faces serious internal troubles.

Xi Jinping’s reimposition of Stalinist ideology has slowed Chinese economic growth and cut off much of China from international thought and creativity. China is growing old before it grows rich. There’s every reason to think that Xi, like Putin, is not given frank and fearless advice and may therefore misjudge reality. There has been something approaching internal disarray in the Chinese government, with senior ministers peremptorily sacked, the majority of the leadership of the rocket force, which commands nuclear weapons, cashiered.

Russia has suffered enormous military and human loss because of the long campaign in Ukraine. Many of its most talented people have fled overseas. It’s a war economy now.

Iran’s government, as far as any outsider can tell, is despised by a large portion of its own population. North Korea is a ramshackle state in every way except militarily. It possesses nuclear weapons and has mastered missile technology.

There’s a pattern here. None of these states is pleasant for most folks to live in, especially if you have an unhealthy proclivity for thinking independently. But they all concentrate on one thing that they do pretty well: building the power to fight.

But there’s something more basic than that. All the authoritarians recognise they are in a conflict, a cold war, with Washington and its allies. They shape all aspects of national policy to serve this conflict. Whereas the public in most democracies – unless like Poland or eastern European states they physically border Russia – are only intermittently aware of this. Their national leaderships on the whole prefer a quieter life. So they will occasionally deliver a rousing speech, and many are willing rhetorically to denounce Russia regularly, but they don’t accept the systemic alliance-wide challenge. And they’re deeply reluctant to call out China.

The legendary US analyst Walter Russell Mead captured the contrast recently when he wrote that all the major authoritarian adversaries now look not to calm crises outside their own regions but to exacerbate them as a way of hurting the US.

Thus, Mead argues, Beijing once would have supported US efforts to protect shipping in the Red Sea and stop the attacks of the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen.

Not any more. Now, argues Mead: “China’s interest in hastening the decline of American power trumps its interest in Middle East stability.”

Similarly, he argues, even 15 years ago Moscow would have worked with Washington to prevent a nuclear breakout in Iran and a nuclear build-up in North Korea. Not now.

“What unites the revisionists,” Mead writes, “is their sense that America, overstretched and internally divided, is ready to be rolled.” So the revisionist authoritarian powers now work to make every regional crisis worse, so that troubles for the US and its allies just keep growing.

One day, they hope, the US or the international system it created will break and, in the entropy that follows, the revisionist authoritarians will each feast in its own region. Mead thinks Washington needs to relearn how to cause trouble for its adversaries. It will do that for Russia. But the Biden administration is chronically wedded to appeasement and detente with Iran, even as the mullahs race towards a nuclear weapon and sponsor conflict and terrorism all through the Middle East.

Matt Pottinger was one of the most impressive national security figures to cycle through the administration of Donald Trump. He resigned from the administration after the January 6 riots. Like Mead, he thinks the Biden administration must become much more aggressive in imposing costs on the authoritarian leaders, especially the Chinese.

He accuses the Biden administration of having a “silo policy”, treating each authoritarian separately without ever linking their actions. Because the administration doesn’t want to use the language of cold war, it pretends there is much less of a systemic struggle under way than really there is.

While the Biden administration started off strongly on China policy, it has now been seduced by a temporary thaw with the Chinese leadership at the declaratory level, while Beijing’s aggressive actions don’t change. Joe Biden has weakened policies in exchange for mere meetings.

Pottinger argues: “The Biden administration offers up managing competition as a goal, but that is not a goal; it is a method, and a counter-productive one at that.

“Washington is allowing the aim of its China policy to become process: meetings which should be instruments through which the United States advances its interests become core objectives in and of themselves.”

This, by the way, is also a perfect description of Albanese government policy towards China, and its mania for “stabilisation” in the relationship. This approach virtually cedes total control to Beijing over whether the democratic nation, be it the superpower, the US, or the middle power, Australia, is “succeeding” in its foreign policy.

It also drains China policy of substance. Thus we have a new military communications agreement with Beijing that the Albanese government hails as a historic success. In the same week, Chinese forces attack Philippine vessels in the South China Sea. None of the incidents in which Beijing’s military has put the lives of Australian service personnel at risk came about because of bad communications. They were deliberate Chinese decisions following deliberate Chinese strategy.

Yet go back beyond strategy and there is a deeper failure, an antecedent failure, in capability.

Elbridge Colby, regarded, with Pottinger, as the other highly influential China thinker in the Trump administration, was a formative influence on the 2018 National Defence Strategy, which attempted to reorient US defence policy towards meeting the China threat. He is likely to be influential if there is another Trump administration and says honestly that no one knows what Xi will do. But, Colby says, Beijing is taking every step to equip itself to fight a major war against the US.

All the authoritarians have built, or are building, wartime economies. Almost all the democracies are half asleep. And it shows. Even now after years of Russian war in Ukraine, Iran closer than ever to nuclear weapons and Beijing massively increasing its nuclear and conventional militaries, embarking on relentless grey-zone attacks on adversaries in cyber, political interference, information warfare and much else, the democracies slumber.

The US Congressional Budget Office produces a swag of figures that show what a macro-mess the US government is. The US budget deficit is now $US2 trillion ($3 trillion), about 7 per cent of GDP. Yet the US economy is allegedly booming, with low unemployment. Next year the CBO thinks interest payments will hit $US1 trillion, more than the defence budget.

The US is hardly alone. France confronts its parliamentary election with a budget deficit of 5.5 per cent of GDP and national debt at 110 per cent of GDP. Britain has national debt of more than 100 per cent of GDP, Japan 250 per cent.

US defence spending is static. The Biden administration’s priorities are at times unfathomable. Biden, like Trump, appointed a land warfare army general as defence secretary, whereas the China military challenge is maritime, missiles, satellites and drones.

The US spends about 3 per cent of GDP on defence. This is manifestly inadequate and way down compared with Cold War spending. Some analysts believe the US could be central to three simultaneous crises – Europe, Middle East, Asia. That would be a way for its opponents to overwhelm it. US allies would be capable of offering only limited support.

All Western governments are caught with ageing populations, growing health costs and an insatiable appetite for transfer payments. The Biden administration’s proposed defence budget bizarrely requested a cut in the production rate of nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarines from two a year to one. Yet nuclear subs are an area of decisive US advantage.

Congress acted against that cut. The US Senate has just authorised another $US25bn for defence. But America can’t win a cold war on the basis that a Republican congress will fix the anaemic military spending of a Democrat president.

Democracies are in disarray. The Albanese government, after two years in office, spends a pitiful 2.03 per cent of GDP on defence, no increase at all. Yet it’s already spending money on far distant AUKUS subs and almost equally far distant Hunter frigates. To accommodate that spending it has cannibalised or destroyed other critical defence capabilities.

Australia is now a less capable defence power than when the Albanese government took office, and nothing will even begin to reverse that for at least the next six or seven years.

Britain, after 14 years of conservative government, spends a substantially smaller proportion of its GDP – 2.28 per cent – on defence than it did in 2010 – 2.48 per cent – when David Cameron came to office, in vastly more benign strategic circumstances. It now has its smallest army since Napoleonic times, while other government spending has run wildly out of control. It’s about to elect a Labour government by a massive landslide, with a party far to the left of its leadership, which will recognise a Palestinian state and enthusiastically embrace every bit of UN international-speak and woke weirdness going.

More NATO allies now spend the minimum 2 per cent of GDP on defence. But no serious democracy, in today’s strategic environment, could think 2 per cent remotely adequate. Most US allies, including Australia, freeload off Washington, and the US is getting sick of this.

If there’s a contest where one side knows exactly what it’s doing, and the other side is distracted and doesn’t really want to compete, it’s not that hard to predict the winner. Democracies must reverse that deadly dynamic.

The world is now split into two hostile, competing camps. One is led by the US and its allies, chief among them Australia, but also Britain, Japan, the NATO nations and the US’s other allies in Asia.