How Australia will struggle to cope with China’s aggression

These are epic times of complexity and unbridled strategic competition. Nothing is more important for Australia than navigating them effectively.

The ministerial meeting is the first in more than two years, but does it mean anything? Trade Minister Don Farrell was unable to secure a meeting with his Chinese counterpart at a multilateral trade ministers’ get-together. There has been no overture from the Chinese foreign ministry to Australia’s new Foreign Minister, Penny Wong.

How Canberra and Beijing manage their bilateral relationship is highly important. But it probably doesn’t affect Beijing’s ultimate strategic plans, which are inimical to Australia. Anthony Albanese, in response to the renewed ministerial dialogue, declared that it was the government in Beijing that had responsibility to improve the relationship: “It is China that has imposed (trade) sanctions on Australia. They need to remove those sanctions in order to improve relations between Australia and China.” That contradicted statements by the Chinese foreign ministry declaring that Canberra needed to act.

Marles said in Singapore that China was attempting to assert sovereignty in the South China Sea in ways that were inconsistent with international law. His meeting with Wei was surprisingly interactive and extended, whereas when the Chinese are in a bad mood with you meetings often devolve into little more than each side reading its talking points.

Marles used the meeting to register Australia’s protest against a Chinese jet fighter intercepting, and dangerously and aggressively manoeuvring around, an Australian maritime surveillance aircraft operating in international air space in the South China Sea.

Wong herself, though not interacting directly with Chinese government officials, said the Albanese government would not sell out any Australian positions to achieve a better relationship with China: “We will always stand up for Australia’s values and interests, whether it’s human rights, the South China Sea or transparent, rules-based trade.”

The Albanese government is attempting to stabilise the China relationship, which means bringing it back to a less dramatic and denunciatory frame, allowing the two governments to transact business more normally.

However, there is a sober realism informing Albanese and his ministers. The government will not compromise national interest to achieve this diplomatic aim or abandon long-held Australian positions to which Beijing objects. It understands that Australia now faces profound and pervasive strategic competition with Beijing in the South Pacific. Wong has made three visits to the South Pacific in three weeks. Nothing could better illustrate the depths of the government’s concern.

China did not succeed in getting 10 island nations to sign up to a single overarching agreement with it, but it did succeed, in foreign minister Wang Yi’s historic tour of the South Pacific, in signing a raft of bilateral agreements.

It has a profoundly disturbing security agreement with Solomon Islands and is extremely active in Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. Many military analysts believe there is a 50-50 chance that Beijing within the next five years will achieve its longstanding policy aim of securing a military base in the South Pacific.

Beyond the South Pacific, the Albanese government also recognises we are in for a long period of deep strategic competition throughout the Indo-Pacific between China on the one hand and the US and its allies on the other. Which brings us back to the two really disturbing and intimately connected strategic claims Beijing made this week.

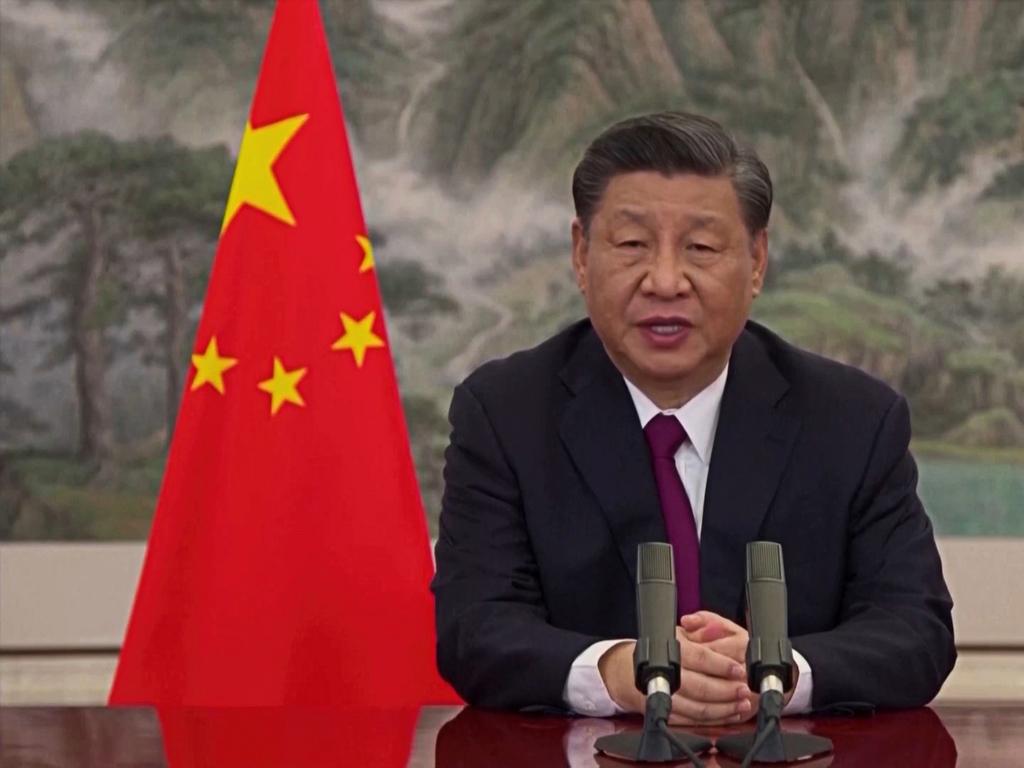

Xi Jinping signed an order authorising special military operations abroad. This allows Chinese military and coastguard to exercise lethal force in circumstances other than war where Chinese resources, infrastructure, personnel or interests are at risk.

This guarantees even more aggressive behaviour by Chinese ships and aeroplanes in the South China Sea and in the waters near Taiwan and Japan. It is similar to the language contained in Beijing’s security agreement with Solomon Islands. It means it’s even more likely Beijing would be able to set up a de facto naval base at very short notice.

Xi’s government has also declared that the Taiwan Strait is territorial Chinese waters and that it has sovereign rights over the strait. The Taiwan Strait, the body of water that separates Taiwan from mainland China, is in fact 180km wide.

The Biden administration immediately declared that the strait is indeed international waters and it will keep transiting through the strait. The US Navy is believed to do this about once a month.

The two moves combined show a determination on Beijing’s part to set up effective exclusion zones in what other nations recognise as international waters or international air space. In Beijing’s view, foreign ships and planes can enter these spaces only with Chinese permission.

So is Beijing spoiling for a brawl with someone or is it just wanting to put more pressure on everyone to establish its regional primacy? What are Beijing’s actual goals? What are the limits of its strategic ambitions?

Mike Green, the new head of the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, who was the Asia director at George W. Bush’s National Security Council and more recently travelled to Taiwan on behalf of the Biden administration, believes Beijing wants a sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific, and in certain respects more widely internationally.

He tells Inquirer: “China wants a situation in which no country in the Indo-Pacific can make any move on diplomacy, technology or with the military which contradicts China’s core interests. And it has defined those core interests to include Xinjiang, Tibet, Taiwan and the South China Sea.

“It also does not accept the legitimacy of any criticism of China’s internal arrangements (such as human rights). It won’t accept the legitimacy of any criticism from the EU, or the African Union or any multilateral organisation in the world. That may appear defensive, but in order to achieve its aims China has to be constantly aggressive. Xi has not only constructed islands in the South China Sea but produced a very active social mobilisation campaign against the West, not just the US but the West, and against democracies. Australia is in the crosshairs because it is a key US ally, in China’s view part of the West, and a democracy.”

Green thinks it unlikely that Beijing will soften in its attitude to Australia, and especially its alleged grievances, such as laws restricting Chinese state-influenced companies from investing in our critical infrastructure, or the ban on Huawei participating in the 5G network, or its other complaints: “There is no case where Xi has softened, not on Korea regarding missile defence systems, not with the US on trade, not with India on the border dispute.”

That suggests that if Beijing decides it has got sick of the trade embargoes it levies on Australia, it may just gradually remove them, without any announcement because the Chinese Communist Party never admits that it got anything wrong.

Xi himself has declared China’s economic and strategic aims are closely linked, and that China will become the world’s most powerful nation, with the biggest economy, the strongest military, dominance in key technologies and the greatest influence.

Justin Bassi, executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and a former foreign affairs adviser to Malcolm Turnbull when he was prime minister, says one of the big challenges for Canberra is that it must deal with the day-to-day management of the bilateral relationship but also safeguard Australia’s interests in the broader strategic competition that Beijing is waging so energetically.

“An improved Australia-China relationship is an important goal, but with two caveats,” Bassi tells Inquirer.

“First, it is China’s actions that must change, not Australia’s. It is China’s economic coercion, arbitrary detention of Australians, dangerous actions in the South China Sea and malicious cyber and foreign interference that form the structural problems in the bilateral relationship.

“Second, even if some or all of these actions cease, Australia must continue playing an active role in the global strategic competition.

“This means working with allies to prevent China from up-ending the rules-based order and contravening its global commitments, whether through undue influence on international institutions, technological suppression, unilateral actions in the South China Sea, developing military bases in the Pacific or systemic and egregious human-rights violations. Australia cannot afford to ignore such behaviour, even if bilateral issues are resolved.

“War in the Indo-Pacific is avoidable. It needs committed long-term deterrence and enforcement. This requires US engagement in the region with support of allies and partners, including Australia. Should deterrence drop, either because of changes in strategic policy or a reduced defence force posture, it not only increases the likelihood of China taking military action but increases the likelihood of China achieving its strategic objectives without military forces, as we saw with Hong Kong.”

Still, there is a sense that we don’t fully get Beijing’s purposes altogether. Consider that Marles rightly called Beijing’s military build-up the greatest since World War II.

Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst at ASPI who has studied the Chinese military closely, agrees with Marles: “It is certainly the biggest and quickest military build-up since World War II. It’s faster and greater than anything the Soviet Union did. China now has the biggest navy in the world. It has a 4.5 or fifth-generation air force, which it’s developed since 2000. It has exceptional cyber capacity and there is the rapid growth of its nuclear forces.”

Bassi emphasises Beijing’s cyber capabilities: “They (China) are not the only malicious actor. But they are the top source of nation-state cyber threats facing Australia and they have been called out many times for their (cyber) activities, including by Australia.”

For many years China’s military budget grew by more than 10 per cent a year. More recently, it has been growing in the 7 to 9 per cent annual range. And much of Beijing’s military expenditure is kept off book.

Xi has often told his troops they need to be able to fight and win for China. But what does Beijing want this vast military for, in both the short and long term?

“They’re doing it for a reason,” Davis says, “because they want to take Taiwan. I think there’s a possibility the Chinese will move against Taiwan in the second half of this decade. There’s also a possibility the US won’t be ready. It doesn’t have enough ships or long-range missiles and the like. It has global responsibilities, whereas the Chinese can focus their force on Taiwan. The US, I think, would struggle against massed Chinese power.

“But if you add Japan and Australia it evens up a bit. You could have a protracted war in which neither side achieves victory. The balance of forces is actually getting better for Beijing. The US has to balance needed force modernisation in areas like hypersonics and autonomous systems against the maintenance of its legacy systems. I think that’s why Biden got out of Afghanistan so quickly. Now you’ve got inflation and a possible US recession, and that won’t help the US military budget.”

Davis also believes Beijing has learnt from Russia’s experience of the effectiveness of nuclear threats. Moscow has deterred NATO from taking direct military action to help Ukraine repel Russia’s invasion because of Moscow’s nuclear threat.

Green believes Taiwan is the security issue that could have the most dramatic escalation possibilities: “The chance of war in the Taiwan Strait has always been low, but it’s getting higher every day.”

This is partly because the stakes for both sides are so high. If Beijing takes Taiwan, Green says, this “would cut the first island chain, isolate Japan and Australia, and represent catastrophic defeat for the whole post-World War II US alliance structure.

“And for the Chinese, defeat in Taiwan is existential.”

Green argues that for all the attention it gets, the ultimate security issues around Taiwan are deeper than most people understand. The US defines its own security as being guaranteed by the island chains of the Pacific.

Davis sketches out some of the consequences of Beijing invading Taiwan: “If China takes Taiwan it will have an offshore base from which to project military power deep into the Pacific, to Guam and Hawaii. It would isolate Japan. It would control the northern entrance to the South China Sea. It would have greater power to coerce ASEAN. This would be the time the ‘limitless friendship’ between Beijing and Moscow would come into play. One result I think would be that Japan and South Korea would go to nuclear weapons very quickly.”

Across strategic circles in the West there is great debate about how to wage strategic competition against Beijing, but to do so, in a phrase the Prime Minister has borrowed but is making his own, in a way that produces “competition without catastrophe”.

Writing in The National Interest, Seth Kaplan, a professorial lecturer at Johns Hopkins University’s Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, argues that the US and its allies should wage a sustained information campaign aimed at the Chinese people, just as they did for the Russian and east European people in the Cold War.

Beijing and its allies have bought up most Chinese language media in the West. They spend enormous amounts of money on propaganda and information campaigns of their own in the West. And they are very active on anonymous social-media campaigns.

But at the moment the Western powers are not making a similar effort to convince the Chinese people that communist rule and international aggression are not in their interests.

In recent years Beijing has explicitly internationalised its ideology. It exports coercive social-control technology and offers political, technical and financial support to authoritarian regimes, arguing the case for their legitimacy, as with Russia.

In all this, Australia has to protect its own interests first, provide its own national deterrent military capabilities, then provide military capabilities that can work effectively in coalition with the US and draw ever closer to like-minded countries, so that association can be a force multiplier for deterrence.

Albanese has inherited these demands. Green gives him very high marks so far, and comments that Labor’s journey on China has been similar to that taken by the US Democrats. Both are dealing with the inescapable reality of contemporary China. Albanese, Marles, Wong and the whole Australian nation face a demanding and dangerous road ahead.

This week China significantly advanced its strategic ambitions, with a new directive and an expansive and ominous claim, while resuming high-level ministerial contact with Australia, with Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe meeting his Australian counterpart, Richard Marles, in Singapore.