How America lost Russia

The Ukraine crisis can be traced back to Bill Clinton’s lack of statesmanship.

NATO and the Atlantic alliance served the cause of Western security well. They helped ensure that the Cold War finally ended in ways which serve open, democratic interests.

But NATO is the wrong institution to perform the job it is now being asked to perform.

The decision to expand NATO by inviting Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic to participate and to hold out the prospect to others – in other words, to move Europe’s military demarcation point to the very borders of the former Soviet Union – is, I believe, an error which may rank in the end with the strategic miscalculations which prevented Germany from taking its full place in the international system at the beginning of the century.

The great question for Europe is no longer how to embed Germany in Europe – that has been achieved – but how to involve Russia in a way which secures the continent during the next century.

And there was a very obvious absence of statecraft here. The Russians, under Mikhail Gorbachev, conceded that East Germany could remain in NATO as part of a united Germany. But now, just a half dozen years later, NATO has climbed up to the western border of Ukraine. This message can be read in only one way: that although Russia has become a democracy, in the consciousness of western Europe it remains the state to be watched, the potential enemy.”

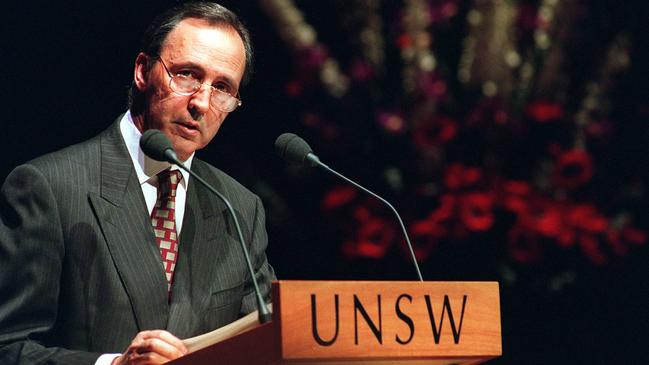

Paul Keating,

September 4, 1997

The lost opportunity of a new post-Cold War order in Europe was president Bill Clinton’s greatest failure. He had his chance in history, inherited from his predecessors from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan – and not least from the last Soviet ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev – and he squandered it.

The latest confrontation in Ukraine, following the 2014 annexation by Russia of the Crimea, is the legacy of Clinton’s presidency. Europe and indeed the world is today imperilled by his failure to bring Russia into Europe and to start dismantling the military architecture of the Cold War.

Two of the world’s most lethal nuclear states are facing off again. The world is now stuck with this peril because the opportunity that existed to remove the threat has now passed.

Strobe Talbott, Clinton’s deputy secretary of state, starts his 2007 memoir The Russia Hand on his role working with Clinton on Russia over eight years, in the closing scene. He describes Clinton’s last visit to Moscow in June 2000, meeting the newly installed President Vladimir Putin, who regarded Clinton as a lame duck with whom he would decline to continue the relationship Clinton enjoyed with his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin. Putin troubled Clinton from the beginning.

Talbott recalls the limousine ride to visit the now ailing Yeltsin for the last time before heading to Air Force One for the last time of his presidency: “As we crossed the river and headed out of the city along Kutuzovsky Prospect, Clinton recalled that it had been the route Napoleon used to march into Moscow with the Grand Armée in 1812. That set him to musing in three directions at once: about Russia’s vulnerability to invasion, its close but complex ties to the West, and its preoccupation with its own history.”

They arrive at Yeltsin’s house where his wife, Naina, has prepared tea and cake for their American guests.

Their daughter Tatyana is also present, and it becomes apparent after eight years she is Yeltsin’s key adviser for she reveals how “we” – father and daughter – worked hard to ensure Putin’s succession to the presidency.

Russia was Clinton’s great exception to what was largely a domestic policy presidency. He devoted a lot of time to it, met with Yeltsin on 18 occasions and visited Moscow five times. Having studied and thought about Soviet policy since they were students at Oxford in the 1960s, Talbott’s point is that it was Clinton who was the so-called Russia hand.

But the story Talbott tells at the beginning of his book has all of the premonitions of Clinton’s impending failure. It may not have occurred to Talbot and Clinton in 2000, and Talbot is not conceding failure at the time of writing his book in 2007, but what else are we to make of this account?

“Clinton settled in for what he expected would be a relaxed exchange of memories and courtesies, but Yeltsin had work to do first. Turning severe, he announced that he had just had a phone call from Putin, who wanted him to underscore that Russia would pursue its interests by its own lights; it would resist pressure to acquiesce in any American policy that constituted a threat to Russian security. Clinton, after three days of listening to Putin politely fend him off on the US plan to build an anti-missile system, was now getting the blunt instrument treatment.

“Yeltin’s face was stern, his posture tense, both fists clenched, each sentence a proclamation. He seemed to relish the assignment Putin had given him. It allowed him to demonstrate that, far from being a feeble pensioner, he was still plugged in to the power of the Kremlin, still a forceful spokesman for Russian interests and still able to stand up to the US when it was throwing its weight around.”

Eight years, for this?

Post-Cold War collapse

Twenty-five years ago, in his first post-prime ministerial speech delivered at the University of NSW, Paul Keating’s prescience about the lost opportunity following the post-Cold War collapse of the Soviet Union is now writ large in the current crisis in Ukraine.

Keating’s assessment that this American error “may rank in the end with the strategic miscalculations which prevented Germany from taking its full place in the international system at the beginning of the century” is a startling one, but hard to refute.

The assessment was shared by the original Russia hand, George Kennan, architect of the Marshall Plan and inventor of the containment policy that provided the intellectual framework of the Cold War. Whereas Kennan’s original Long Telegram sent from Moscow to Washington in February 1946 premised containment in economic and political terms, Truman’s doctrine would transform it into a policy of military containment that would last until 1991, when the Soviet Union finally collapsed.

By then well into his 90s, Kennan maintained his interest in Russia, occasionally consulted by Talbott and Warren Christopher on behalf of the Clinton administration. His edited diaries contain entries from when he was an 11-year-old in 1916 to a centenarian in 2004, the year following which he passed away. Russia is a long thread through his journal.

In early January 1997, Kennan wrote from his home in Princeton that “the Russians will not react wisely and moderately to the decision of NATO to extend its boundaries to the Russian frontiers” and “thus will develop a wholly and even tragically unnecessary division between East & West and in effect a renewal of the Cold War”.

By month’s end, Kennan formed the view that the “deep commitment of our government to press the expansion of NATO right up to the Russian borders is the greatest mistake of the entire post-Cold War period”,

In a February 8 opinion piece in The New York Times titled A Fateful Error, Kennan went public with the view “that expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era”.

He wrote:

“It is … unfortunate that Russia should be confronted with such a challenge at a time when its executive power is in a state of high uncertainty and near-paralysis. And it is doubly unfortunate considering the total lack of any necessity for this move. Why, with all the hopeful possibilities engendered by the end of the Cold War, should East-West relations become centred on the question of who would be allied with whom and, by implication, against whom in some fanciful, totally unforeseeable and most improbable future military conflict?”

So what was the necessity for this move? Kennan alludes to it in the opening of his opinion: “In late 1996, the impression was allowed, or caused, to become prevalent that it had been somehow and somewhere decided to expand NATO up to Russia’s borders. This despite the fact that no normal decision can be made before the alliance’s meeting, in June.

“The timing of this revelation – coinciding with the presidential election and the pursuant changes in responsible personalities in Washington – did not make it easy for the outsider to know how or where to insert a modest word of comment. Nor did the assurance given to the public that the decision, however preliminary, was irrevocable encourage outside opinion.”

If the necessity of this fateful error was Clinton’s electoral imperatives in 1996 – that he would pre-empt the meeting of the alliance not due until the middle of 1997 – then the more shame to his presidential legacy. Talbott tells of his and Christopher’s attempt to elicit an encapsulation of the new post-Cold War policy as simple and compelling as his original “containment”, Kennan strongly demurred. He was not entirely happy with the policy for which he had become a legend and advised against trying to capture the policy in a slogan. When they reported back, Clinton laughed, saying: “Well that’s why Kennan is a great diplomat and scholar and not a politician.” Yes, at the end of the day a politician was all that the 42nd president turned out to be.

Moscow was vulnerable

Keating was unaware he and Kennan shared the same analysis. It was in the days before Google. Keating’s starting point is the geography of western Russia and eastern Europe: as Clinton recognised, Russia was vulnerable to invasion. Napoleon and Hitler, and Charles XII before them, had all been enticed by the geography, even if the extreme climate and the long, broken supply lines eventually cruelled them. Russian security paranoia is well-grounded in history and geography. Paul Robeson’s homage to the Red Army Choir’s Polyushko Polye – Meadowlands or Song of the Plains in English – sings of this landscape.

Keating returned to the subject a decade later in a 2008 speech to the Melbourne Writers Festival. By its enlargement of NATO “the United States failed to learn one of the lessons of history; that the victor should be magnanimous with the vanquished”.

“At some time, the United States will be obliged to treat Russia as a great sovereign power replete with a range of national interests of the kind other major powers possess.

“In the meantime, the great risk of this sort of adventurism is that with NATO’s border now right up to the western Ukraine, the Russians will take the less costly military option of counterweighing NATO’s power by keeping their nuclear arsenal on full operational alert.

“Russia is the only country in the world with the capacity to massively damage the United States to the point of seriously maiming it. And ditto for Western Europe. Wouldn’t you think that when the Russians surrendered their empire in 1990, US policy would have been adept enough to find an intelligent place for them in the overall strategic fabric?

“That is, to have Russia as part of an enlightened framework of intelligent coexistence, thinking back beyond the Cold War to when we partnered with them to defeat Hitler. But even more than that, in people terms, to invite their 160 million, battered by the 20th century, into the comity and wealth of nations?

“Instead, the United States has conducted itself as unrivalled powers have done throughout time; unchecked, it exploited its position. It has ring-fenced Russia, treating it as a virtual enemy with its west European and central European clients egging it on.”

Absence of statecraft

Keating said 25 years ago there had been “absence of statecraft”. So what is statecraft? Let me attempt an answer.

It is the strategic deployment of power that advances the long-term interests of states, through the use of available diplomatic, political, economic and military means. No actor without these means or within close proximity to these means can exercise statecraft. Statecraft is the intersection between strategy gained from deep study and long contemplation, and the means by which that strategy can be effected. It is the extremely difficult business of visionary realism: having a large vision of what is possible while being constantly grounded in the realities of the strategic situation: what it is, rather than what one would like it to be.

As the most powerful leader of the most powerful state in the world, Clinton’s political leadership with all of the diplomatic, political, economic and military resources at his disposal, nevertheless did not amount to statecraft. He didn’t have a strategy like George Kennan following the Iron Curtain.

What should that strategy have been? Strobe Talbott records the most promising articulation of what the vision should have been, and it came from the man whom Clinton tried to play, Yeltsin, thinking that his handling of the Russian was clever statesmanship, rather than its abrogation.

It was in Budapest in 1994.

Talbot writes:

“When Yeltsin’s turn came immediately after Clinton’s, he started on a note that sounded eerily like what Clinton himself had said on other occasions – and should have said on this one. ‘It’s too early to bury democracy in Russia,’ said Yeltsin. ‘The year 1995 will be the year of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II. Today, half a century on, we come to realise the true meaning of the great victory – and the need for historic reconciliation in Europe. There should no longer be enemies, winners or losers, in that Europe. For the first time in history, our continent has a real opportunity to achieve unity.’

“Then, glowering, he shifted into a minor key: ‘To miss that opportunity means to forget the lessons of the past and to jeopardise our future … Europe, even before it has managed to shrug off the legacy of the Cold War, is at risk of plunging into a cold peace.’ ”

What was needed was a strategy for the staged decommissioning of NATO concurrent with a staged nuclear disarmament, and its replacement with a new structure inclusive of Russia, to secure the peace and guarantee the smaller states the security that was finally in prospect.

Talbott writes that in early March 1992, former president Richard Nixon wrote then president George H.W. Bush a memorandum urging American support for Yeltsin and warning that unless there was an American response comparable to the Marshall Plan for Europe after World War II, the United States and the West would “risk snatching defeat from the jaws of victory”.

Nixon wrote: “The hot-button issue of the 1950s was ‘Who lost China?’ If Yeltsin goes down, the question of ‘who lost Russia?’ will be an infinitely more devastating issue in the 1990s.”

William Jefferson Clinton lost Russia.

Noel Pearson is a director of Cape York Partnership and Co-Chair of Good to Great Schools Australia.

“I believe a great security mistake is being made in Europe with the decision to expand NATO.