Horror of The Exorcist created a hit of eccentric masterpiece

Fifty years ago, Mike Oldfield’s misunderstood Tubular Bells was languishing – until William Friedkin found it perfect as the soundtrack for his horror classic, The Exorcist.

William Friedkin had already won a best director Academy Award before embarking in 1973 on his sixth film, The Exorcist. He would never make a film as popular or as good as it again.

Mike Oldfield completed his first album, Tubular Bells, in 1973. He would never make music as popular or as it good again.

In a series of accidents Friedkin would have rejected as too absurd in any script submitted to him, the director chanced upon an unlabelled acetate of Tubular Bells in a Los Angeles office and immediately sensed its unconventional opening passage was the music he was looking for to match his disquieting film about demonic possession.

It was handy for Oldfield that he started Tubular Bells with the disorienting, almost anti-gravitational piano motif with its transfixing 15/8 time signature; the impatient Friedkin would never have got much further in. He knows little about Tubular Bells and to this day mistakenly believes that the voice announcing the instruments at the end of side one is Oldfield’s. It is unlikely he has heard side two.

Other than each having had four wives the men have nothing in common. They have never met or spoken. But the art and instinct of each is critical to the legendary status of them both.

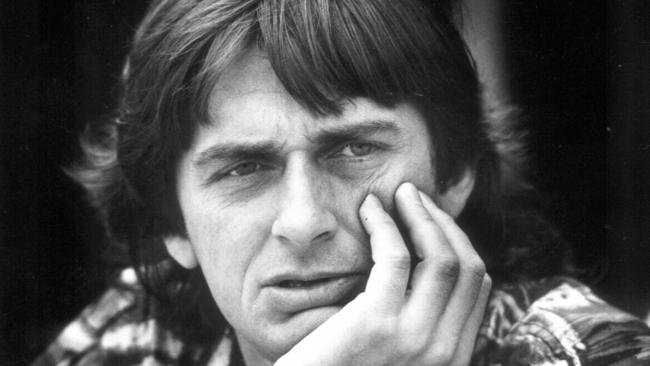

Oldfield was a mentally unwell, gifted musician, who, with his sister Sally’s help, had played in some low-key folk and experimental outfits as far left of the heartbeat of popular music as it was possible to be while still living on the outskirts London.

Oldfield had been extroverted and gregarious as a child and “the leader of the gang”, according to his sister. But things changed when their mother fell pregnant when Oldfield had been about 10. The family was happily looking forward to the birth of the boy who had been named David. Their mother Maureen went to hospital to have the child, but neither David nor Maureen returned. The Oldfield children were told by their GP father Raymond that the child had had a hole in his heart and had died and that their mother had gone to “a nice place by the sea”.

David had Down syndrome and lived more than a year. Maureen later returned home addicted to barbiturates and beset by mental health issues. She would rock back and forth issuing animal-like howls. Oldfield dealt with all the upset by retreating to his room and working on the handful of chords Sally had taught him on his first guitar. He had soon mastered much more and with some school friends did some two-pound gigs. Sally suggested they perform together and so their duo, Sallyangie, was born and in 1969 released a largely unlistenable album, Children of the Sun.

It has been pointlessly re-released from time to time, but the only aspect of it that is of any interest is the evidence of the speed with which Oldfield was developing as a guitarist.

Sally persevered as a singer and songwriter and in 1983 issued the mesmerising, unaccountably overlooked album Strange Day in Berlin. It remains a quirky highlight of 1980s music.

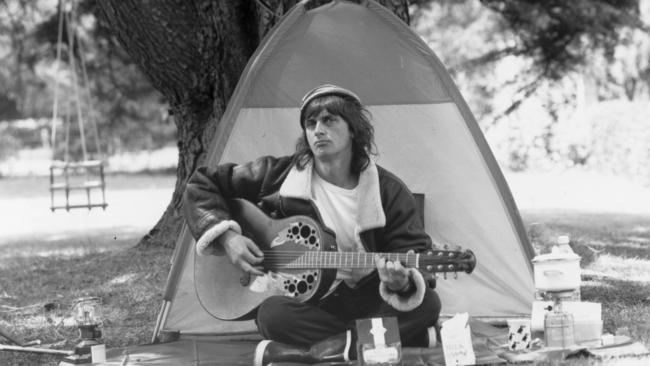

Oldfield’s mental problems intensified when they broke up and he lived the hippy life in that awkward, barefoot-despite-the-cold, English way. He played in a band with his older brother Terry on flute. Just small, poorly-paying college events. Terry would go on to become a composer and play on his brother’s recordings.

Oldfield auditioned for the band Family, at that time John Lennon’s favourite, when its bass player Ric Grech left to join the supergroup Blind Faith that included Steve Winwood, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker. But Family were unimpressed with the young man who had only recently picked up the bass.

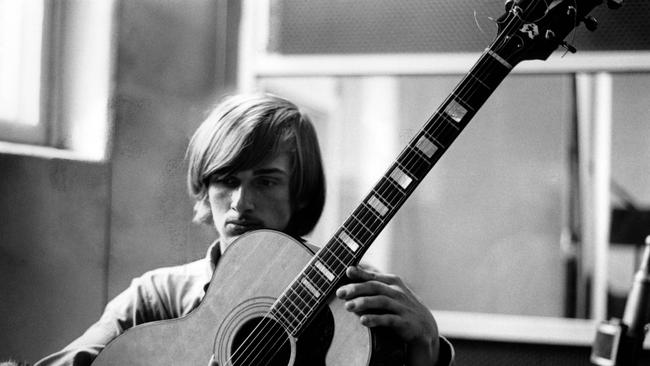

The influential and gifted musician and singer Kevin Ayers was looking for a backing band having just left psychedelic outfit Soft Machine that he founded with Melbourne’s Deavid Allen. He recruited Oldfield whose bass playing had vastly improved, and would soon be at virtuoso level with an adventurous, Paul McCartney-like aspect to it. Not long after, he was playing mandolin in the Edgar Broughton Band and with both acts recorded albums at EMI’s London studios that had yet be renamed Abbey Road. In long hours there he was exposed to the then leading-edge technologies and radical recording techniques, while teaching himself other instruments in idle hours.

By now Oldfield was living in a small flat in Pimlico’s Victoria Square; a decade earlier author Ian Fleming had lived there writing the James Bond novels and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Oldfield was experimenting with LSD and suffered trips so fraught he thought he would die. For anyone with delicate mental and emotional underpinnings LSD can be lethal.

He moved in with Ayers, who was also trapped by addictions. Ayers left the band and the house and left Oldfield with his simple, two track reel-to-reel tape recorder and the keyboard player’s cheesy Farfisa electric organ. Together they would change his life.

Aged 19, he started working on short musical passages putting down his bass on one channel and a guitar or the Farfisa on the other. One of the tracks he made at that time was the opening motif of Tubular Bells – the music later to underscore the key scene in The Exorcist when actor Ellen Burstyn walks home from Georgetown University and a series of predictive scenes flash by deftly unannounced.

As his collection of musical oddments grew, so did Oldfield’s confidence that he could turn them into a single thematic suite of music. He shopped the tapes across London, but it was a vision only he could see until he bumped into a young, over-confident would-be entrepreneur from a privileged background who’d given up school to sell budgerigars before starting a student newspaper and then a mail-order record business that flourished by illegally avoiding import duties.

This would fund the record label Richard Branson planned and which he called Virgin. He went into debt to buy a country estate near Oxford which he turned into a residential recording studio. Playing sessions there for a now-forgotten band, Oldfield passed his tapes on to some sound engineers employed by Branson. One, Tom Newman, thought them promising. (Newman would go on to make his own albums on which he played everything, including the beautiful Bayou Moon in 1986, but he was already a footnote in rock history for being at The Beatles rooftop concert and having a painting of his rest clearly visible behind Ringo Starr’s drum kit.)

Branson heard the tapes and also thought they showed more than just promise. Oldfield moved in to The Manor House studios and worked there on his ideas in downtime with Newman. Branson paid for the instruments – about 20 – that Oldfield said he needed. The tubular bells were free. Oldfield spied them being moved into a van after a session by the Velvet Underground’s John Cale and asked that they be left behind. They might come in handy.

The first side of the album came quickly. Most the music was composed and it was Oldfield’s idea to have the often drunk dandy Vivian Stanshall – whose father had insisted he develop a plummy accent – act as MC and introduce the instruments one-by-one as they entered the first side’s coda. Oldfield had met Stanshall at The Manor House and was familiar with his eccentric Bonzo Dog Doo Da Band. Stanshall’s mental health was also fragile, but his band had featured in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour and Paul McCartney had produced their novelty hit, I’m The Urban Spaceman. After leaving the Bonzo band he turned up regularly on BBC radio and television in the manner of a poor man’s Monty Python – he knew them well. At one stage he sheared off his bright red locks and changed his stage name to Sean Head. His best mate and drinking buddy was dangerously nutty Who drummer Keith Moon, another regular at The Manor House. Stanshall was drunk the night he had to utter those memorable 26 words starting with “grand piano!”. In the end, after several failed takes and missed cues, Oldfield wrote them down. (Stanshall died in a fire at his top-floor flat in North London in 1995.)

Pleased with the recorded result, Oldfield played it to Branson. Branson knows nothing about music. His favourite song was Cliff Richard’s tacky 1962 hit Bachelor Boy. Branson thought Oldfield’s masterpiece “might need some vocals”. Oldfield fixed that on the disjointed second side with what is known as the Caveman segment.

He drank half a bottle of whisky and spat out guttural sounds across four minutes of music. Branson never interfered again.

Curiously, Oldfield ended the whole thing with the traditional Sailor’s Hornpipe, not an instrument, but rather a 200-year-old jig to which Captain Cook had sailors dance on deck to maintain fitness. You will be familiar with it as the theme to Popeye the Sailor Man.

Branson released it as Virgin’s first record with the catalogue number V2001, giving birth to an empire now known as the Virgin Group with more than 70,000 employees worldwide and with annual revenues of $32bn.

But it didn’t happen overnight. Few knew what to make of Tubular Bells which originally was played on the BBC just once – and only side one. Most UK reviewers were enthusiastic, but the Americans were hostile. Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau dismissed the record as “a clever novelty … light and showy” weeks before seeing another act he would hail as the future of rock and roll, Bruce Springsteen, whose producer and manager he would become.

It sat on the lower levels of the UK charts, but slowly gained popularity. Those who hadn’t yet bought it had often heard it at Saturday night parties where, by early summer 1973, the record was being played by Londoners who wished to be considered cool. That July it entered the charts and rose steadily.

As the over-budget and over-deadline filming of The Exorcist drew to a close, Friedkin, having rejected music written for the film as lacking subtlety, or being too churchy and liturgical, still sought something with the “tones and textures of irrational fear”.

He called an old mate at Warner Brothers, Larry Marks, to ask if he could come over and listen to some music. Marks had a few scores to his name as a producer and singer: he had produced Helen Reddy, and in 1969 sang the Scooby-doo cartoon series theme.

Marks told Friedkin to come over and look in the record library. When he arrived, Marks wasn’t there, but some white label vinyl acetates of English records being considered for US release were on Marks’ desk. Friedkin pick one up and put it on a turntable. It happened to be Tubular Bells. It happened to be side one. He happened to like it and the most unlikely marketing campaign for the record was born.

The Exorcist premiered on US screens on Boxing Day 1973. It remains the 9th most successful film of all time and the highest grossing horror film, and the most popular R-rated movie ever. Five weeks before it won two Academy Awards, Oldfield’s album won a Grammy for best instrumental composition.

The record went to No. 1 in the UK, Australia and Canada and No. 3 in the US. It has sold 16 million copies.

And the horror and madness of The Exorcist extended into real life. Friedkin used real doctors, nurses and staff for the scenes at New York’s Bellevue Hospital where Linda Blair’s possessed character undergoes a cerebral angiogram. The real radiologist, Paul Bateson, in 1977 murdered Addison Verrill, a film reporter for Variety, and is believed to have killed perhaps half a dozen gay men in unsolved murders where victims were dismembered and thrown into the Hudson River in bags.

Some of the themes of The Exorcist would have resonated with Oldfield too.

His mother never recovered from her bouts of severe mental illness. And she must have been concerned about her son. In Oldfield’s last conversation with her before she died in 1975, by which time he had become an international superstar, she asked him: “You know what it’s like, Mike. Don’t you?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout