Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy helped reshape world

However, he had not reckoned with the extraordinarily savvy ability to respond of Israeli prime minister Golda Meir. Kissinger had made the point to the prime minister that he was first an American; second the US secretary of state; and only finally was he a Jew. Deadpan, Meir responded that Kissinger had neglected the fact, in Israel, they read documents from right to left.

Kissinger’s career, which spanned both the 20th and 21st centuries, is replete with anecdotes such as that, usually about the exercise of American power on the global stage.

It is extraordinary to note that Kissinger served only briefly in public office, from 1969 to 1977. First, Kissinger was national security adviser to president Richard Nixon, then simultaneously, for a time, secretary of state, which office he continued under Nixon’s successor, president Gerald R. Ford. The turbulence of those times was remarkable and Kissinger’s creative diplomacy continues to leave a resonance in the modern world, especially in relations between the US and China, and in the Middle East.

For Kissinger, the tendency of US politics, especially in congress, to emphasise the moral superiority of American perspectives needed always to be tempered with the realities of global pressures. This is not surprising if we remember that Kissinger’s doctoral thesis at Harvard University in 1954 was titled A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812–22, focusing on the emergence of a far more stable Europe in the wake of Waterloo.

Clearly, the emphasis in Kissinger’s scholarship was on stability and predictability. Kissinger had first-hand experience of the alternative, as his family had fled Nazi Germany in 1938 for the US. Kissinger believed firmly that the rise and appalling consequences of Nazism would not have been possible without the disintegration of Weimar democracy and the grievous political errors made in Germany at the time.

He would come to apply this lesson, sometimes wrongly, as in Chile in 1973, to crises as they challenged US foreign policy.

For Kissinger also understood at first-hand the consequences of war and its aftermath. As a sergeant in the US Army’s 84th Infantry Division, Kissinger looked into the abyss of the Holocaust in Germany in April 1945.

For 22-year-old translator Kissinger, the experience was profound and deeply shocking.

Having witnessed the horrors of the concentration camps on April 10, 1945, he wrote in a letter reproduced in Niall Ferguson’s biography Kissinger, Vol. 1, 1923-1968: The Idealist, “Skeletons in striped suits lined the road … Cloth seemed to fall from the bodies, the head was held up by a stick that once might have been a throat. ‘What’s your name?’ And the man’s eyes cloud and he takes off his hat in anticipation of a blow. ‘Folek … Folek Sama.’

“ ‘Don’t take off your hat, you are free now.’ ”

Kissinger’s contributions to the current global dynamic cannot be discounted.

It was Kissinger who created both the concept and reality of shuttle diplomacy as he flew between the Middle Eastern capitals of Tel Aviv and Cairo, seeking a settlement for the Yom Kippur War.

When current US Secretary of State Antony Blinken flew recently between Middle Eastern capitals trying to seek an effective solution to the Israel-Hamas conflict, it was still labelled shuttle diplomacy.

But it was Kissinger’s capacity to see the larger picture that distinguished him from other policymakers, and Kissinger was able to marry a vigorous and commanding intellect to a sense of realism in office.

His healthy ego was sometimes an impediment, but never insurmountable.

However, US presidents did not always have Kissinger’s sense of immediacy in foreign policy.

There is a famous Washington story, probably the stuff of legend, that holds Kissinger storming into the Oval Office in 1975 to insist that president Ford deliver an address to the nation on the situation in Angola. Ford is said to have looked up from his papers and said: “Henry, if I try to tell the American people about Angola, they would think I’m talking about the creation of a new soft drink.”

Only a man from Grand Rapids, Michigan could understand that as clearly as Ford did.

Certainly, another president from Whittier, California knew his man far too well.

Nixon grew used to Kissinger’s tantrums and threats of resignation, especially during crises such as the India-Pakistan war of 1971.

Kissinger may have avoided the worst of the Watergate scandal that engulfed Nixon, but it was Kissinger’s endless complaints about the leaking of confidential negotiations that proved part of the process in the Nixon administration whereby the “plumbers’ unit” was given birth. Add G. Gordon Liddy and Watergate was inevitable.

Kissinger loved secrecy, whether it was the clandestine flight from Pakistan to Beijing that led to the breakthrough with China, or the secret war in Cambodia, or the backroom conclave with Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho that eventually culminated in the settlement of the Vietnam War.

Intriguing to observe that Australian Labor leader Gough Whitlam was vindicated in his overture to China in 1971 by the White House releasing details of Kissinger’s simultaneous secret visit.

Kissinger made enemies, and they were not necessarily ideological: the Republican Right loathed him over detente with the Soviet Union; the Democratic Left detested him for failings on human rights.

Kissinger himself cultivated contacts on both sides of the aisle in Washington, DC.

Had the Democratic candidate for president in 1968, senator Hubert Humphrey, won the election, Kissinger might well have found a comfortable niche in his administration. He served Republican Nixon, who at times treated him brutally.

At one time, after hearing Kissinger’s analysis of America’s security situation, Nixon stated, “Thank you, Henry. Now, can we have an American view?”

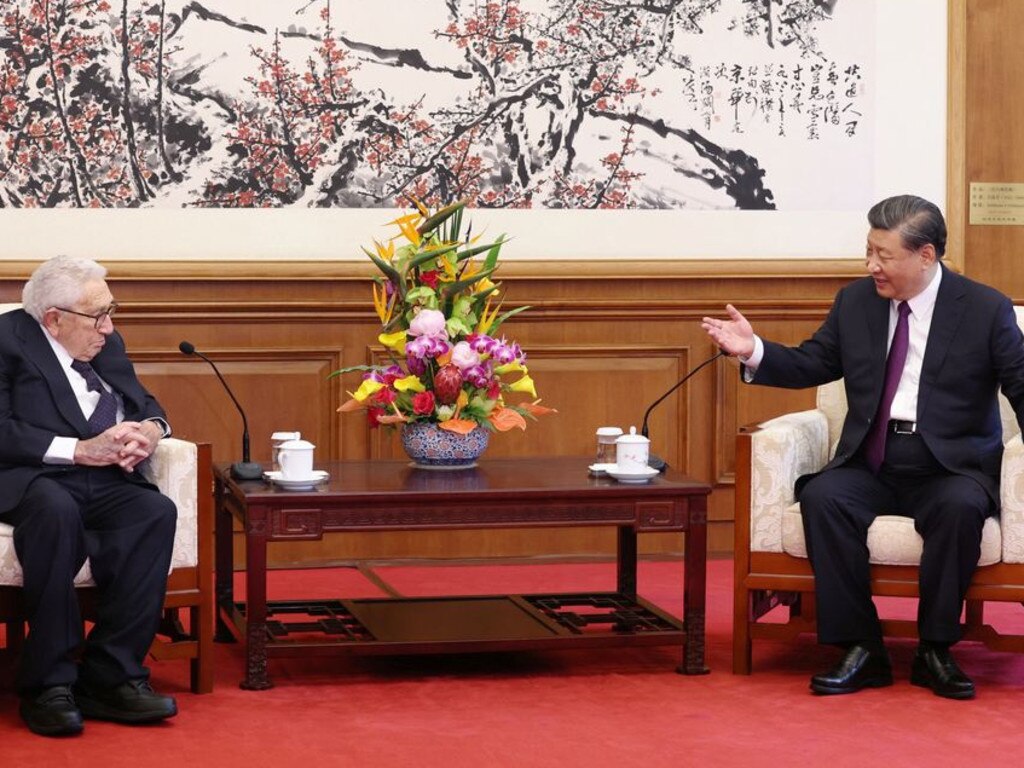

The world as it is today was shaped, in part, by Kissinger. Right until his death, he remained influential, supporting President Joe Biden on Ukraine, while remaining sceptical about American exceptionalism.

On a visit to Sydney some years ago, Kissinger addressed a lunch and began with his own anecdote.

He described a social function in which a woman had come up to him very confidently and said: “Dr Kissinger. You are supposed to be a fascinating man. So fascinate me.”

Kissinger’s audience applauded in appreciation, just as knew we would.

That was part of his charm, but moreover, was essential to his skill.

Stephen Loosley is a governor of AmCham, Sydney.

It was rare for Henry Kissinger, who died at his home in the US state of Connecticut on Wednesday, aged 100, to be bettered by one of his interlocutors.